Marshall's fractured wrist could spell the end of UNC's title hopes

GREENSBORO, N.C. -- John Henson was standing all by himself Sunday night in the middle of the Carolina locker room, the first time in over a week that no one wanted to inquire as to the status of his sprained left wrist.

That's because, as someone said to Henson, "Your wrist is old news now."

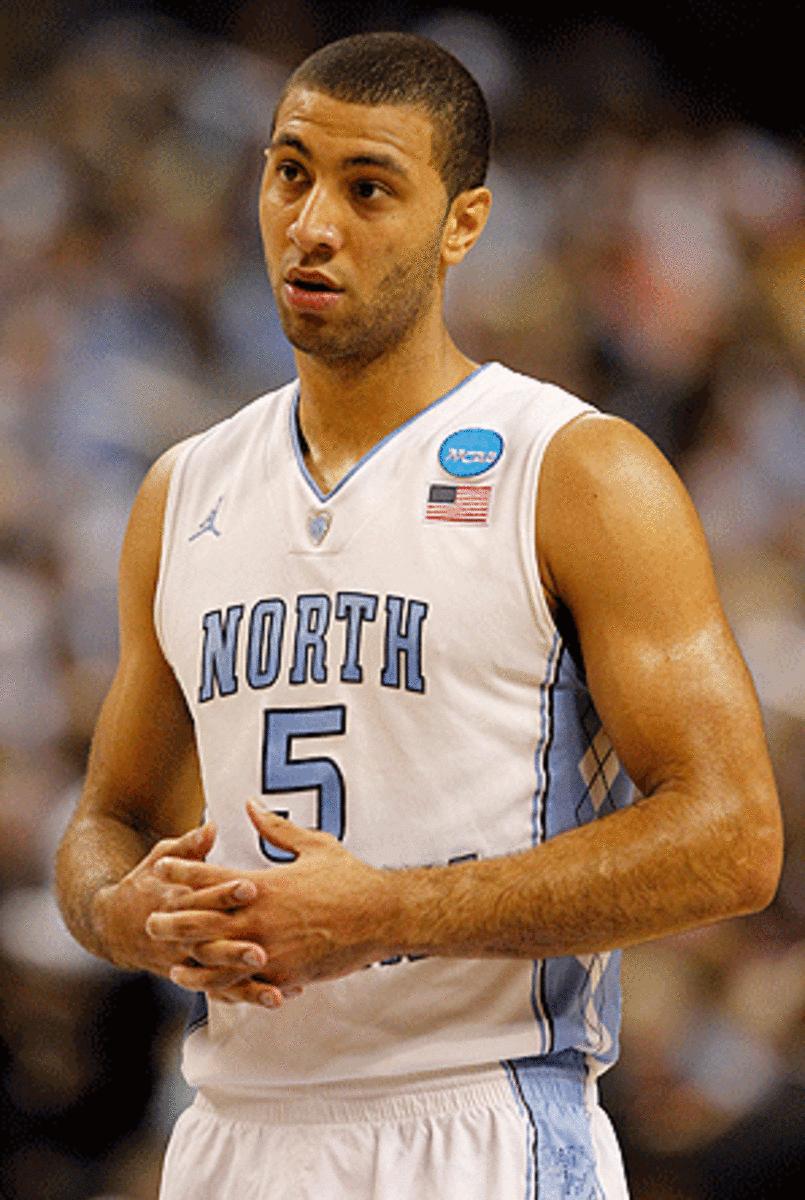

It was a brief moment of levity in a stunned and very somber Carolina locker room. Yes, the Tar Heels beat Creighton 87-73 on Sunday to advance to the Sweet 16, but you wouldn't have known it from the mood among the players and coaches after the Tar Heels learned that their indispensable sophomore point guard, Kendall Marshall, had suffered a fractured right wrist after being sent flying by Creighton's Ethan Wragge with 10:56 left in the game.

Marshall came out of the game at the next dead ball but returned after sitting for less than two minutes of action. He then stayed in the game -- even picking up his final two assists on a pair of Harrison Barnes three-pointers that put the contest away -- until coming out for good with 1:56 remaining, at which point he got immediate attention from Carolina trainer Chris Hirth.

The game was no longer in doubt, but North Carolina's championship hopes very much are. Henson may be back, but Wrist Watch 2012 continues with new urgency in Tar Heel Nation. Without Marshall, Carolina would lose not only the player who leads the nation with 351 assists this year -- an ACC single-season record and just 55 shy of the all-time NCAA mark -- but the player whose unmatched vision and court sense is the primary reason Carolina has scored more points than any team in the country this year. His injury could be a death sentence to the Tar Heels' dreams of a third national title in eight years and would blow an already chaotic Midwest Regional wide open.

While officially stating that his status for the Sweet 16 and beyond is yet to be determined, Marshall's red-rimmed eyes seemed to indicate that he fears the worst. "I'm not hurt that I can't play," he said while trying to fight back tears. "I'm hurt that I can't help my team."

The Tar Heels have seen this all before. In 1969, 1977, 1984 and 1994 otherwise excellent North Carolina teams have seen their seasons derailed by late-season injuries to their starting point guards. UNC head coach Roy Williams has experienced it too; his 1997 Kansas team carried a 34-1 record into the Sweet 16 but lost there to Arizona, in part, due to a broken wrist suffered by starting shooting guard Jerod Haase, now a UNC assistant. And the Tar Heels are already in the midst of their fifth consecutive season of losing a player to a season-ending injury.

The timing of Marshall's injury is especially cruel not just because it is in the tournament but because the Tar Heels finally looked to be resembling the title favorite everyone expected when the season began. Marshall was also playing his best ball of the season, averaging 13.8 points per game on 62.2 percent from the floor and 53.3 percent from the three while still contributing 10.5 assists in five postseason games, a big jump from 7.2, 42.7, 31.3 and 9.6 in the regular season.

There is unlikely to be a final answer on Marshall's status until sometime during the week. But given that Henson sat out for nine days with a sprain (he returned Sunday and played extremely well, with 13 points, 10 rebounds and four blocked shots) it is difficult to imagine that Marshall would be able to return in less than a week with a fracture and that even if he did he would be his usual, All-America-caliber self.

"Luckily it's my right hand," said Marshall afterward. "If it was my left hand we'd have some problems."

Carolina already has a problem. Marshall's precision passing fuels the Tar Heels' up-tempo engine. As Duke coach Mike Krzyzewski said after Marshall shredded the Blue Devils for 10 assists in Cameron Indoor Stadium, Marshall's uncanny knack for getting teammates the ball in the right place at the right time is so effective because it makes the move for his teammates so that all they have to do is shoot it.

Marshall has averaged almost 33 minutes per game this season, and 35 minutes since his primary back-up Dexter Strickland, also the team's starting shooting guard, tore his ACL in mid-January. In Strickland's absence, Williams has given spot minutes to freshman Stilman White, usually around TV timeouts to try and steal as much rest as possible for Marshall without much time running off the clock.

On Sunday, Marshall played the first 13 minutes and sat for just 81 seconds of game action before returning to finish out the half. White averages fewer than five minutes per game and though he has a stellar assist-to-turnover numbers (19 assists and just five turnovers) he has never played more than 11 minutes in a game. He was signed as an emergency option last summer after Larry Drew II -- the starter at Carolina until Marshall bumped him to a back-up role at midseason last year -- quit the team in February 2011.

White, who will leave after this season on a two-year Mormon mission, said of his increased role, "It's definitely helped. I've gotten a lot of confidence as the season has gone on."

Williams' only other options are Justin Watts, a 6-foot-4 senior who has played every position but center and runs the point on at least two occasions, and a point-guard-by-committee approach.

Asked what Carolina will do next, a shaken Barnes said, "I have no idea."

Williams, who walked dejectedly out of the Greensboro Coliseum with his head down and talked with Marshall's parents after the game had ended, probably doesn't either. "When you go to the Sweet 16" said Williams after the game, "it's supposed to be a lot more fun than this."

The notoriously superstitious Williams had to feel like karma was on his side: his team had opened play in Greensboro, where they began their run to the 2009 title while answering questions about the status of an injured starter (then point guard Ty Lawson; now Henson); the next stop was St. Louis, where Williams won his long-awaited national title with Carolina in 2005; then would come the Final Four in New Orleans, where North Carolina won the championship in both 1982 (with Williams as an assistant) and 1993 (defeating Williams' Kansas team that had won the Midwest Regional in St. Louis, in the semifinals).

During each of those stops by the mighty Mississippi, Williams goes to spit in the river for good luck. Like every Carolina fan about to descend on the gateway City, Williams better start flooding the river with loogies. The Tar Heels are going to need it.