Guillen mess is result of culture seeking manufactured opinions

Ozzie Guillen is a man who says what's on his mind, except when he says what almost certainly isn't on his mind, as when he expressed his admiration for Fidel Castro, whom he couldn't possibly admire if he thought about it, which he didn't, because he's a man -- like a lot of men -- who says what's on his mind even when (spoiler alert) there is nothing there.

This is called having an opinion, and having an opinion is not just your right in a free country but increasingly your obligation. It is better to express an opinion that you don't have than to keep private an opinion that you do have because having a "take" -- one that's paradoxically sharp and pointless -- is what's important.

This is not entirely a bad thing. When so many of our manufacturing jobs have gone overseas, we can still manufacture opinions in America. Want a baseball manager's take on Fidel Castro? He might not have one in stock, but he'll be happy to make one for you on the spot.

Why you would want a baseball manager's take on world leaders -- Ron Washington on George Washington? Bobby V on Benedict XVI? -- is a question for another day. For now, it's enough to say that strong opinion is the coin of the realm in public life, regardless of who is expounding on what.

It is a guiding principle of most columns, presidential debates, political ads, bumper stickers, comment sections and cable news punditry that the only thing in the middle of the road is roadkill. So say what's on your mind, even if your mind has nothing to say. This makes your mouth a ventriloquist's dummy for your brain, but so what? It will also make your call-in radio show -- or your call to a call-in radio show -- sing.

When Time magazine did its Q and A with Guillen, Ozzie was just providing the A. And what an A he has proven to be in various interviews over the years. But when he said that he admired Castro, what Guillen actually believed was: "I don't admire Castro." And that's not just my opinion of his opinion, for "I don't admire Castro" is exactly what Guillen said Tuesday at a press conference in Miami, where his contrition appeared more genuine than his astonishing profession of affection for the dictator.

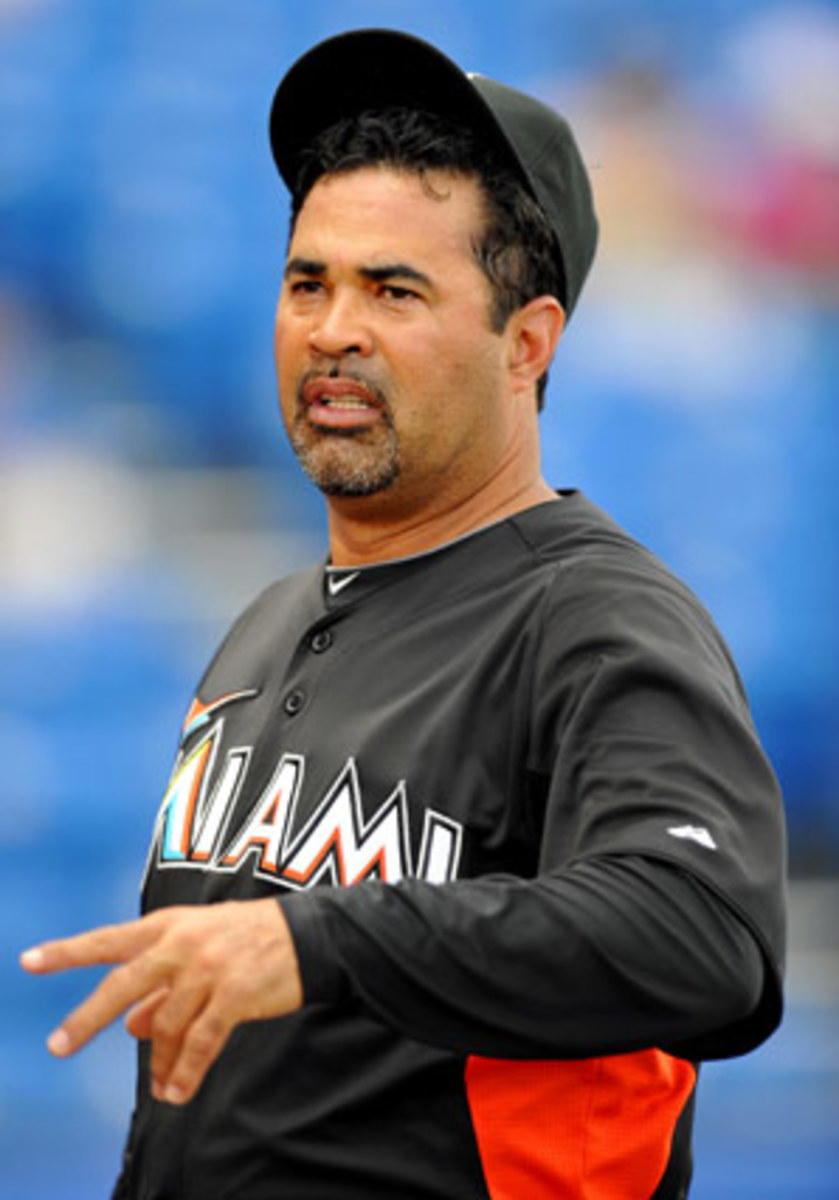

If you are the manager of the Miami Marlins, who play their games in Little Havana, praising Castro amounts to trolling your own fan base. Why someone would want to do this is not entirely clear, beyond craving attention, but neither is it evidence of a long-held love of Castro. On the contrary, it is evidence of never once having thought of Castro until -- or even while -- extolling Castro's instinct for survival.

It is, in other words, another contrived "take" in a world where the take sign is always on. In baseball history, only Shelley Duvall, swinging a Louisville Slugger while backing up the stairs in The Shining, has had more takes with a bat in hand than Guillen.

That bat scene in The Shining required 127 takes, according to legend and The Guinness Book of Records, a piece of movie trivia I throw in here for two reasons. First, I fear all of us -- Guillen, those of us commenting on Guillen, and those of you inevitably commenting on the people who comment on Guillen -- are unwittingly starring in a movie of our own. It's called Blowhard 2: Blow Harder.

The second reason to raise The Shining is this: I have space to fill and no more opinion with which to fill it. My opinion about Guillen's opinions has run its course. Or rather, failed to run its course, having hit the wall at the 700-word count, when this column typically limps through the break tape at 800 words.

This is the greatest failing of all -- failing to have an opinion -- and I really should manufacture two more paragraphs of outrage. Except there's a danger in expressing opinions you don't really hold. Almost every one of us is leaving a legacy on the Internet, where nothing ever goes away. And so we need to update the old anatomical analogy about opinions. Opinions are like bones. At any given moment, every one of us has at least 206 of them, and they're all that we'll leave behind when our time on Earth has passed.