We don't know athletes like Junior Seau, just image that they present

How could Junior Seau shoot himself?

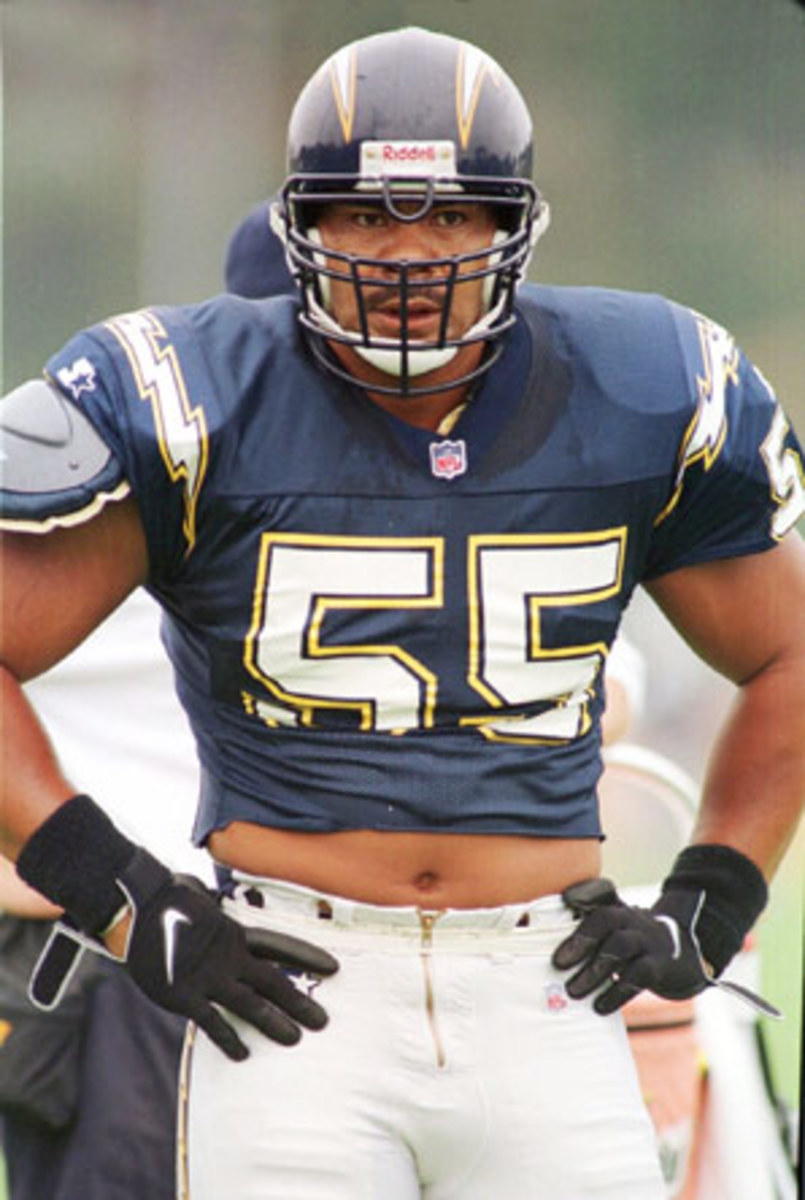

Famous and adored, regal and respected, Seau was a 12-time Pro Bowl linebacker. He was the sports face of a city -- San Diego -- that also happened to be his hometown. He had it all. Didn't he?

His foundation had raised more than $4 million. His restaurant was among the most popular in San Diego. You couldn't find a former teammate who was not drawn to his talent, his stoicism, his heart and the respect he showed the game. He would be a Hall of Famer on the first try. He was just 43. So much to live for. So we thought.

I didn't know Junior Seau from Ken Griffey Jr., and I spent a decade covering Griffey. Many times, at some function or another, fans asked me, "What is Griffey really like?''

Every time, I'd say, "I have no idea.''

I could describe what one of Griffey's home runs looked like as it left the yard. I could paint the picture of his grace in centerfield. I could tell you how he treated me (with disdain, mostly). What I couldn't tell you was who he was.

We don't know athletes. We like to think we do. We have an image, and these days that image is massaged more than ever, by handlers and social media and by the athletes themselves. When Andre Agassi hawked cameras saying, "Image is everything'', he was ahead of his time.

It could be that the violence of the NFL helped kill Seau. He's the third former NFL player in just over a year to shoot himself. Dave Duerson and Ray Easterling both suffered mentally from concussions incurred while playing. It could be that Seau longed for purpose outside the game. For lots of retired players, especially the great ones, nothing replaces the beautiful noise of a Sunday afternoon.

It could be a combination of both. We don't know. What we know is this: A man the public saw as vibrant and essential is dead after shooting himself in the chest.

I remember Eugene Robinson. In 1998, Robinson was winding down a 16-year NFL career as a starting safety for the NFC champion Atlanta Falcons. He was a very good player, a two-time Pro Bowler. He was also universally acknowledged as a "great guy'' off the field.

What's Eugene Robinson really like? Oh, great guy. Just a great guy.

The day before the '99 Super Bowl in Miami, the Christian organization Athletes in Action presented Robinson with its Bart Starr Award, for "outstanding character.'' That night, police arrested Robinson for offering $40 to an undercover female officer posing as a prostitute, for oral sex.

We just don't know.

"Most of the image is derived from the uniform,'' said Cincinnati Reds third baseman Scott Rolen. I'd asked Rolen Thursday how much of what the public knows of its jock heroes is fact, and how much is fable. "Fifty-fifty,'' he said, "and I'm being generous.

"Who we are as people -- our personalities, our character, how we are as husbands and fathers and friends -- is sometimes judged by our performance. If a guy's a great hitter, he must be a great guy.''

No one is saying Seau was not a towering figure, on the field and off. By all accounts, he was "a great guy.'' It's also true that celebrities want us to know what they want us to know. Athletic greatness does not automatically confer moral rectitude, or assure a wonderful life.

We see this over and over, from Kirby Puckett to Tiger Woods. Clay feet are everywhere among the great guys.

Stanley Wilson was a fine fullback in the 1980s in Cincinnati. He also had a cocaine problem. Then-Bengals coach Sam Wyche went so far as to put Wilson up at his home during the season to keep Wilson from the devil powder.

The Bengals made a Super Bowl run in '88. Wilson was a big part of that. He was a devastatingly good blocker and well-skilled in executing a play-action fake. He also enjoyed telling us how he'd ditched the cocaine train.

Stanley wasn't always outgoing, but he was charming, with a smile stolen from the right side of the sun. We wanted to believe him. He was a good story. More, he was a good guy.I thi

The night before the Super Bowl, Wilson disappeared from the Bengals team hotel and embarked on a three-day drug excursion. The NFL banned him for life.

In October 2010, police arrested Seau and charged him with suspicion of domestic violence. Later that day, Seau drove his SUV off a cliff. He said he'd fallen asleep at the wheel. If there were any red flags then, they never made it up the pole. This was Junior, beloved and cherished symbol of San Diego's civic pride. A true hero, without mortal problems.

And maybe that's still true today. We don't know.

I didn't know Seau. I knew the image, though. It was nothing like what we're seeing after his tragic death.