League focusing on mental health, but players must buy in

It was guard Nate Newton and, ironically, Michael Irvin -- the Hall of Fame wide receiver at the center of much of those antics -- who helped break the ice between the buttoned-up Brooks and a roster that eventually became convinced that she had to be a management spy. "They were watching me, watching my behavior, who I talked to, if I was consistent," said Brooks, laughing as she recalled Newton's bid to set the terms of her employment. "He said, 'You're going to have to decide who you're going to work for -- us or them. If we open the door for you, you're one of us.'"

The NFL has since opened its doors to many more like Brooks while raising mental health awareness and increasing the resources to address it. According to statistics from the National Institute of Mental Health, an estimated 26.2 percent of adult Americans have a diagnosable mental disorder. But it's a truth not easily acknowledged in pro football, a game as much predicated upon creating and exploiting vulnerabilities in the mind as in the body. The passing of Junior Seau -- the seemingly unbreakable Pro Bowl middle linebacker revealed as stunningly fragile in the wake of his sudden death inside his Oceanside, Calif., home from a self-inflicted gunshot wound on May 2 -- could be the rare catalyst that encourages current and former players to take their mental health more seriously.

Rookies, though, have little say in the matter; the NFL is making them take their mental health more seriously. In addition to the annual rookie symposium, first-year players now are required to submit to further mental health education at team facilities. The "Rookie Success Program" spans eight clinician-taught classes covering subjects like stress management, domestic violence and substance abuse. Along with boosting the players' emotional IQ, "We try to reinforce the point that if you need help, we can guide you in the right direction," says Dr. Angela Charlton, a manager for the league's Player Engagement division, which tackles mental health.

Beyond that first year, it's on the players to be proactive. Each NFL team has an officer to cater to players, most of them titled "Director of Player Development" (or DPDs for short). They coordinate with mental healthcare professionals, some of whom are even on staff. Overall, the mental healthcare community has become vastly more adept than it was a decade ago at dealing with football's fickle client base.

Back then Brooks, one of a handful of clinicians embedded with NFL teams, had to hip the outsiders in her field to the environment into which they were entering. "One of the big things they didn't understand is that if you don't know the culture, you can't be effective," she said. A doctorate degree in clinical psychology and the years of practice Brooks had in the field before taking up with the Cowboys couldn't fully prepare her for every facet of the job.

Like today's DPDs, Brooks chiefly matched clients with the healthcare providers in and around the Texas Metroplex area best equipped to deal with their concerns. However, in addition to Cowboys players, she also worked with coaches and executives as well as their loved ones. She didn't conduct therapy sessions or administer treatments. What she tried to do was disabuse people of "the movie version" of how afflictions like depression and alcoholism gain purchase, and act as a sounding board in matters clinical (post-concussion symptoms), situational (a death in the locker room) or both (a violation of the NFL's substance abuse policy).

Confidentiality was her calling card. "I would tell the players, 'I have a license, and if you feel I'm violating your confidence here's the number you can call to report me,'" Brooks said. "They loved that." When one newcomer to the team responded to her polite welcome with intimidation, Brooks did not hesitate to tell him to "step outside" and then proceed to "lay his soul to rest."

Brooks' feistiness would have been considered unprofessional in a more traditional counseling setting, but it was essential for her survival on the job. During Brooks' eight-year tenure, the team leaned on her heavily for emotional support during a tumultuous stretch marked by more arrests, freak injuries and the deaths of All-Pro offensive tackle Mark Tuinei in 1999 and second-year tailback Ennis Haywood in 2003. The following year Brooks left the Cowboys and eventually started her own Dallas-based firm that counsels players through their post-retirement years.

None of today's DPDs are as credentialed as she is. Kansas City Chiefs director of player development Katie Douglass, who holds a Master's of Education in counseling/sports psychology, is one of the few who comes close in a field dominated by ex-jocks, who bring to the position an innate understanding of locker room culture and implicit trust from players. That's one of the reasons the league is fine-tuning a certification program, "that teaches what we think are the core skills needed," says Adolpho Birch, an NFL senior vice president who oversees the Engagement division.

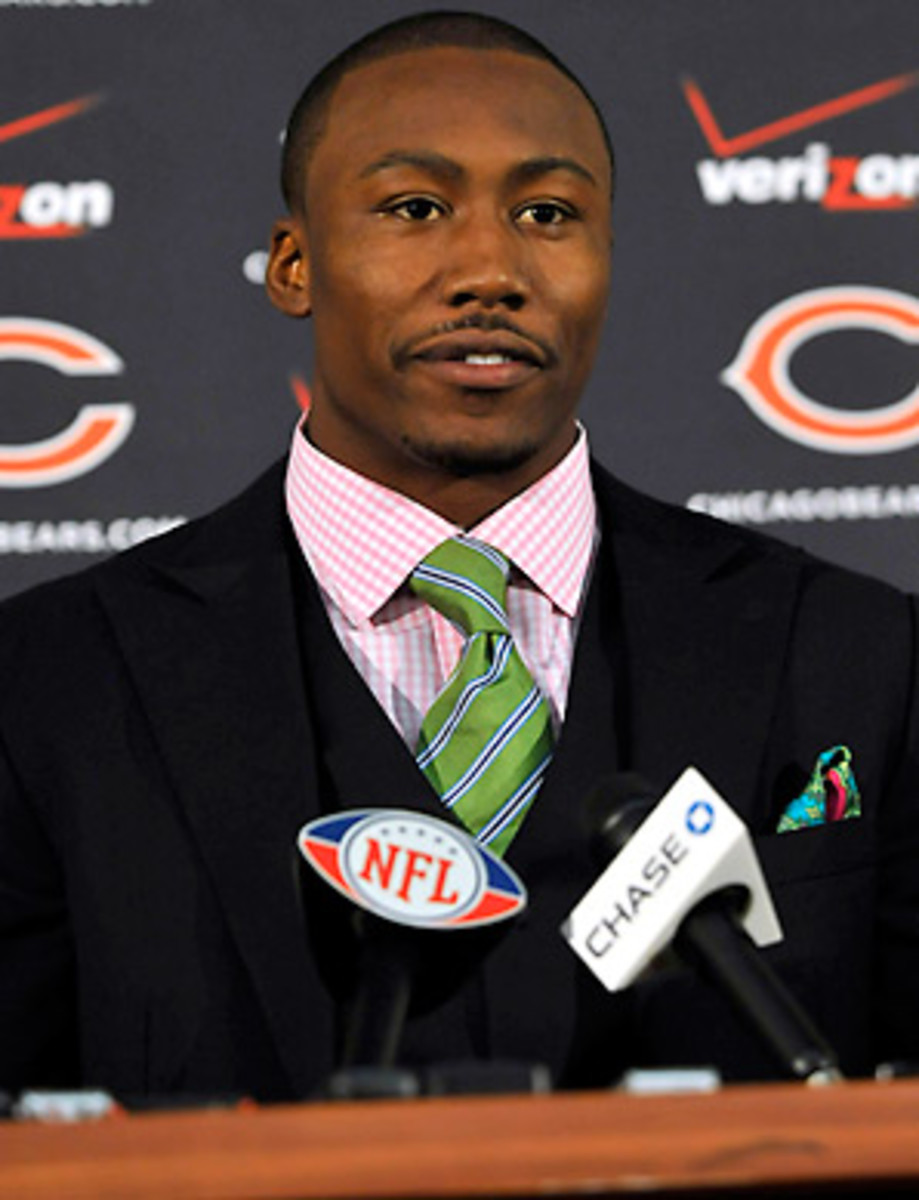

The hope is to create a stigma-free environment in which players feel more comfortable working through their mental health issues. Bears receiver Brandon Marshall reached a breakthrough of sorts last July, when he announced that he had been diagnosed with borderline personality disorder; the moment hints at the strides engagement programs are making behind the scenes.

Last month, former defensive tackle Terry "Tank" Johnson made a similar disclosure to a private audience of 40 at Georgia Tech during a seminar for the league's career transition program, whose mission parallels that of Brooks' independent firm. The key is capturing players within their first three to four years of retirement. Seau was just two years and three months removed from retirement when he took his life. Donna Moultrie, a marriage counselor turned chauffer who served as Seau's personal driver in the years his career was winding down, saw -- even then -- how "the struggle of ending something he was so passionate about was really difficult for him," she told San Diego's 10News.

Johnson said he sought out DPDs for clarity often in a six-year career with the Bears, Cowboys and Bengals that was fraught with hardship. Along with multiple concussions, he suffered the twin losses of his cousin, NFL linebacker Marquis Cooper, who went fatally missing after his boat capsized in turbulent water near Clearwater, Fla. in March of 2009; and Bengals star receiver Chris Henry, who fell off the back of a truck to his death while quarreling with his fiancée nine months later.

Johnson thinks the biggest reason players don't open up is financial. Between football's unguaranteed salaries, meticulously tracked injuries and teams' itchiness to discard players at the first sign of damage, players fear that too many visits to the team shrink could come back to haunt them at the negotiation table. "You end up with this paper trail of information that can be used against you in the future," Johnson said. "With guys not having guaranteed contracts, they're a lot less apt to say 'This or that is wrong with me.'"

In retirement, Johnson, who hung up his cleats for good after his release from the Bengals last August, has little incentive not to enlist the league's help now as he segues out of the NFL spotlight and into more quotidian ventures. (He hopes to launch an online marketplace for athletes to swap goods and services, called eliteexchange.com, in August.) Counseling is a big part of the league's career transition program, as is the availability of neurological care to players vested under the Bert Bell/Pete Rozelle retirement plan.

Help reaches all players now. The onus, he says, is on them to reach back. "It's in every athlete's best interest to understand where the game is going," he says. "I think if you can factor that into how you deal with your problems, it'll make all the difference."