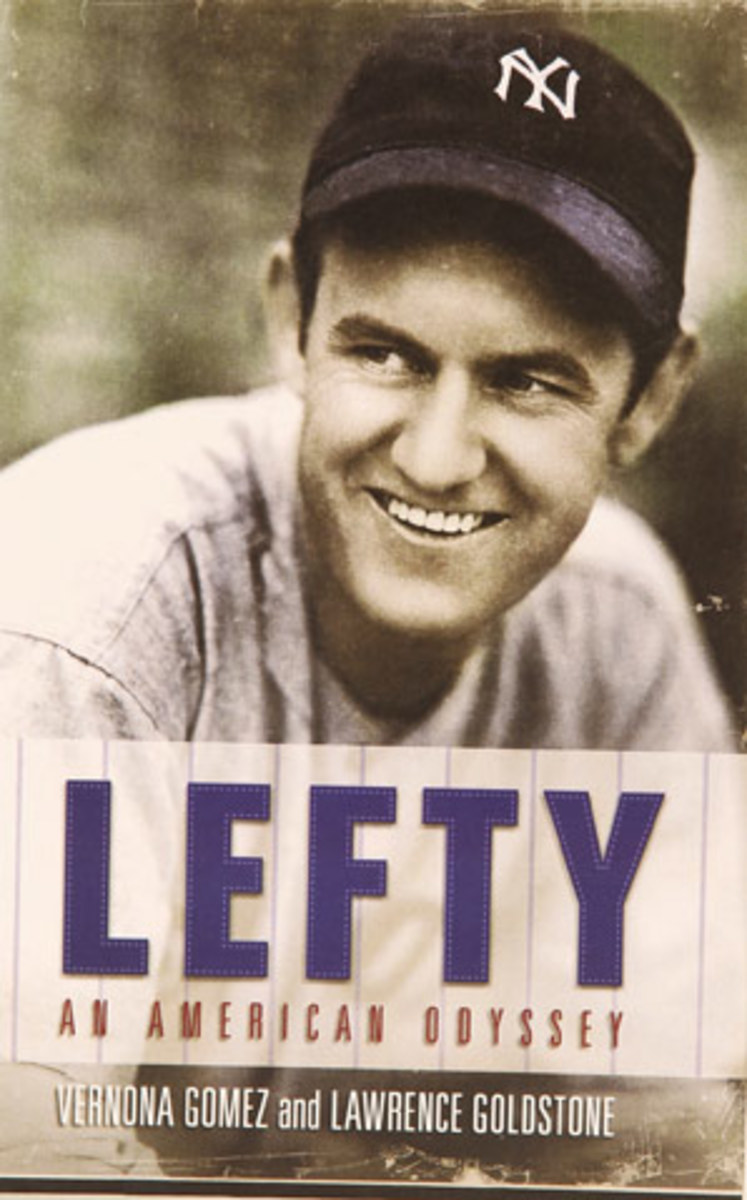

Lefty: An American Odyssey

From LEFTY: An American Odyssey by Vernona Gomez and Lawrence Goldstone. Copyright © 2012 by Vernona Gomez. Published by Ballantine Books/The Random House Publishing Group, a division of Random House, Inc.

However much his on-field performance might have declined, in 1934 Babe Ruth remained a renowned figure, particularly in baseball-crazy countries such as Japan. As it happened, a tour of that very nation by a team of American Leaguers had been planned for the postseason. The team would be led by the Philadelphia Athletics' manager and part owner, Connie Mack, who turned out to be willing to cede his position as the all-star squad's manager, in public at any rate, to that other aspiring manager, the Bambino himself. For Mack and the other organizers of the tour, principally John Shibe, the A's majority owner, and Matsutaro Shoriki, owner of Yomiuri Shimbun, Japan's most widely read newspaper, Ruth's presence would ensure a huge success in Japan. Babe would get to remain in the public eye, and the stunt would draw attention to his managerial skills. A rumor even got started, source unknown, that the 72-year-old Mack was retiring and Babe would replace him on the A's. Babe claimed no knowledge of it; Mack made no comment.

When Babe signed on for the tour, so did New York Yankees ace Lefty Gomez. Other than a barnstorming stop in Juárez, Mexico, Lefty had never been out of the U.S., and he was voraciously curious about other cultures. Babe Ruth's wife, Claire, was to go as well, as was their daughter, Julia, so Lefty took his wife, the Broadway musical star June O'Dea. The trip would serve as the honeymoon their careers had not allowed Lefty and June. Lefty brought along his newly purchased 16-mm camera to commemorate the journey.

Other stars followed, including newlyweds Lou and Eleanor Gehrig. Lou, who had been part of a 1931 tour of Japan, had wanted to return to Japan ever since, and like Lefty, his Yankees teammate, he decided the tour would be a perfect honeymoon. The entourage would sail from Vancouver on the Empress of Japan on Oct. 20. After a short stopover in Honolulu, the Empress would continue across the Pacific.

Although six baseball tours had previously been made to Japan, the first by a team from the University of Chicago in 1910, the 1934 version would be the grandest yet. The team consisted of 14 major leaguers. Six of them were future Hall of Famers; the rest, chosen by Shibe and Mack, were solid if not spectacular players, many drawn from the A's roster.

Besides Lefty Gomez there were three other pitchers: Earl Whitehill, Clint Brown and Joe Cascarella. There were two catchers, the Athletics' Charlie Berry and a backup journeyman named Moe Berg, who became well known after World War II for having been a spy. Berg took lots and lots of photographs in Japan, some of which may have been used to plan bombing raids during the war. He claimed they were; others in a position to know insisted they were not.

The 16-mm films that Lefty took on the tour, however, could well have been studied by the War Department. "Late in the 1936 season, during batting practice in a game against the Red Sox," Lefty said later, "I was in the bullpen warming up when Moe Berg asked to talk to me. He was interested in the films I had taken of Yokohama harbor and asked if I had any of Shanghai and Hong Kong. I didn't have a clue what he was driving at. Moe gave me an address in Washington and asked me to send my pictures there. He told me they'd be sent back. I mailed the film to Washington. I don't know specifically who received it. They kept the film for seven or eight months, and then it was returned with a letter that expressed thanks."

*****

On the Empress of Japan, Lefty and June were given a large stateroom between Babe and Claire's room and Julia's. The voyage did not begin well. The sea was rough and stormy, and there was no shortage of intensely seasick passengers. Joe Cascarella, who was counted on to do a quarter of the pitching in Japan, wouldn't be in shape to do much of anything when the ship finally docked. "I was sick most of the time," he said. "Lefty, too, but he was better off than me. I lost 20 pounds. Connie Mack wanted to put me on a ship and send me home. I told him, 'Another ship? I'm only going to get sicker going home, so I might as well stay.' "

Cascarella, who was single, was also unlucky in shared accommodations, drawing Charlie Gehringer, one of the two other unmarried players on the tour. "I hated him because he was always healthy," Joe said. "Every morning he got up, punched his chest and said, 'I feel great! I'm going down and eat a big breakfast.' I'm sick and I can't get up out of bed. That was Gehringer's idea of humor."

June Gomez was spared -- she won a $5 bet with Babe that she wouldn't get sick on the trip -- as was Eleanor Gehrig, but Claire and Julia Ruth couldn't get out of bed. The Ruth family did have one healthy member, as June noted: "Babe never gets sick. He smokes, drinks and eats like a horse. Three steaks for breakfast; lunch, tea and a huge dinner. He is superhuman, I think. I have never seen anyone like him."

The seas eventually turned calmer, so except for severe cases such as Cascarella's, most of the party began to enjoy the voyage. Julia Ruth recovered more energetically than most. "She dated Moe Berg and Frank Hayes on the trip," June wrote, "and from then on Julia and Frank were an item back in New York."

Sometimes Babe would wake June and Lefty up at 7 or 8 a.m. to engage in whatever shipboard activity the big fellow favored that day. The Japanese crew did everything possible to see that the passengers enjoyed themselves. "The stewards wait on you hand and foot," June wrote, "but it's tough to get them to understand you. They say yes but don't know what you're talking about."

Lefty was also feeling better, as Julia Ruth attested: "After dinner, there was dancing to a swing orchestra. We all sat ringside. ... Daddy, Claire, me, and the other ballplayers and their wives. June, so elegant in her evening gown, and Lefty would be out in the center, cutting fancy dance steps, and June couldn't understand why we were all laughing our heads off. She didn't know that when Lefty spun her around, he pushed his upper plate out with his tongue, and gave us all a big toothless grin."

One source of friction, however, had become apparent. "There was a little bit of an unsatisfactory situation with Eleanor Gehrig and Claire Ruth," Cascarella said. "It never flared out but was obvious to most of us." After the trip, it was widely reported in the press that Babe and Lou were no longer speaking and that the rift had to do with their wives. Subsequently, reports surfaced that Babe had become furious with Lou because Gehrig's mother had accused Claire of treating Julia better than Dorothy, the daughter Babe adopted with his first wife, Helen. Babe was reported to have told Lou never to speak to him again off the ball field, a dictum he maintained for several years.

Whether or not Claire and Eleanor did or did not like each other, Lefty always insisted that the war between Lou and Babe was vastly overblown by sportswriters. "You keep hearing these stories about Babe and Lou not hitting it off," he said. "When you consider ballplayers are together from February until October, there are going to be squabbles. But Babe and Lou, enemies? Not a chance. Babe was an extrovert in the extreme, and Lou was an introvert. Babe threw his money around, and Lou counted his pennies. Babe liked the high life, and Lou enjoyed the opera and the philharmonic. Babe was glib with the press; Lou found it hard to come up with a snappy quip. There may have been comments here and there that caused temporary chagrin, but Babe and Lou were teammates and friends on and off the field. I respected the fact that they lived life their own way. Nothing more, nothing less."

An entry in June's diary after the team had been in Japan for a week suggests the same: Claire and I went by Eleanor Gehrig's room laughing, so she called out and invited us in for a drink. We sat and talked until 1 a.m.

*****

The Empress of Japan docked in Yokohama on Nov. 1, 1934. The next day, upward of 500,000 people lined the streets of Tokyo to welcome the American ballplayers. Wide boulevards were shrunk to narrow alleys with barely enough space for the automobiles to pass through. The main attraction, of course, was Babe Ruth, who led the procession in an open limousine, waving and smiling to the adoring crowds.

"When we walked off the train at the Tokyo station," Lefty recalled, "the Japanese spectators awaiting Babe's arrival rushed forward, almost crushing him. Babe had to push his way through the crowds as they were running by, tearing at his clothes for souvenirs. They pulled at his jacket, his pants, his hat, and the crowds and their passion for Babe never let up for one second wherever he went."

The tour was not popular with everyone in Japan, however. The nation was already simmering with ultranationalist fervor. In February of the following year, a young army officer would attempt to behead Matsutaro Shoriki as he was leaving his home. But Shoriki, short and bald, was also a judo master and took only a glancing blow with the sword. He recovered and lived until 1969.

The first game was played in Tokyo in front of 55,000 fans. For the majority of games against the American juggernaut, Shoriki had assembled the best players in the country, the All-Nippon team, including 11 who would make the Japanese hall of fame. In the opener, however, the Americans played a team of former college players and won 17-1.

The results hardly changed when the All-Nippon team played. The Japanese lost all 18 games on the schedule, by a combined score of 189-39. But on Nov. 20, a 17-year-old pitcher named Eiji Sawamura lost by only 1-0, on a Lou Gehrig home run in the seventh inning. (Many U.S. newspapers incorrectly credited Ruth with the seventh-inning blast, illustrating the subordinate role Lou played to Babe through the early '30s.) Sawamura struck out nine, including a streak of Gehringer, Ruth, Gehrig and Jimmie Foxx.

"I pitched twice against Sawamura," Lefty said. "He was young, but he instinctively knew how to take command when he was on the mound. He was fast, with good location and a tantalizing curveball." Connie Mack immediately offered Sawamura a contract, but Sawamura, still in high school, did not want to leave home. He died almost 10 years later to the day, when his ship was torpedoed by Allied forces in December 1944. The Japanese equivalent of the Cy Young Award is named for him.

*****

When a game wasn't scheduled, Lefty and June got to experience Japanese culture, usually with Babe and Claire. June wrote of visiting a Meiji-era sacred shrine, where millions of visitors tossed coins; sitting on pillows shoeless as they ate sukiyaki served by geishas with pomaded hair; riding in rickshaws; and having massages. Then there were the toilets. "The funniest yet . ... a hole in the floor, and you have to practically lie down to go," June said. "Lefty was in one when a Japanese girl came in and asked him for his autograph."

The cuisine was predictably exotic -- a good deal of sushi and sashimi, of course, then virtually unknown in the States, but also some even more unusual items. "One dish that caused dismay among the wives was baked woodcock," June said. "The little brown bird was served on a dish with its head still on. No one would eat it except me. I said, 'Oh, I love that!' So they all dumped their birds on my plate, and I sat there whacking their heads off and ate them all. But that was the exception. The Japanese food in '34 was tasty and elegantly served. The geisha girls never let the sake cup be empty. Once we dined at the famous club that was known to serve only dignitaries like Queen Mary, Queen Elizabeth and Charles Lindbergh."

A vegetarian on the trip might have had a difficult time, however. June said, "There were 'honey-wagons,' horse carts carrying pails of human manure that the Japanese used to fertilize their plantings. When the ballplayers and their wives became aware that all the vegetables were fertilized by human manure, nobody wanted to eat them."

On Nov. 10, a cold, damp day in Tokyo, Lefty struck out 19 in a 10-0 victory in front of 65,000 fans, including an imperial prince. Lefty wasn't supposed to pitch that day. He had gone nine innings just two days before. But Cascarella still had trouble standing up for nine innings, let alone pitching them, so Lefty stepped in.

Sometimes the Americans went to the dignitaries instead of the other way around. Cascarella reported on a sumptuous banquet at the royal palace. "Emperor Hirohito was the 'Son of Heaven,' a god, and mere mortals like us were not supposed to cast an eye on him," the pitcher said. "Most Japanese had never heard or seen him. And yet, here are the ballplayers and their wives in his presence in a magnificent reception hall, exchanging pleasantries through an interpreter. Protocol demanded that we be respectful and stand facing the Emperor, and there was a lot of bowing. Suddenly we heard Moe Berg conversing with Hirohito in Japanese, and the Emperor was hanging on his every word. I don't know what Moe said, but the Emperor's face broke into a smile." (Berg was famously known as a man who could speak 10 languages but was unable to hit a curveball in any of them.)

When the players made trips to outlying cities, the wives remained in Tokyo. Once away from the capital, both the crowds and the conditions deteriorated. Spectators sometimes numbered as few as 5,000, and Lefty remembered playing games in pelting rain. In some cases, a layer of snow ringed the field. "The dugouts were freezing," Cascarella would recall. "We sat on the benches, huddled together, shivering in the overcoats we wore over our uniforms. On the dirt in front of us were braziers, little boxes of fire, the length of the bench."

Players slept on straw beds in primitive hotels, four to a room, and had beer for breakfast. "In Hakodate, we stayed at a hotel that was so cold, we had to keep our overcoats on in our rooms," Cascarella said. "I remember sitting up all night playing bridge with Earl Whitehill, Charley Gehringer and Jimmie Foxx because it was too cold to sleep."

"The games were mostly one-day trips," Lefty said, "and the only one who had a bed on the train was Babe. The rest of the players sat up at night or slept on the floor. Babe's portable bed was set up next to the toilet. The toilet was just a hole in the floor, so of course it stunk, and Babe complained about the smell. The rest of us just laughed at him: 'Babe, you're complaining? You're the only one with a bed.' "

*****

On Nov. 28, in Kyoto, Lefty pitched for the seventh time in the series. June remembered him being ecstatic. "He won 10-1, and he also got three hits and two walks. A perfect day. He told Mr. Mack he had found his league at last."

But although Lefty made light of the overwork, it had become palpable. On one occasion, two days after pitching a complete game in cold, damp weather, he pitched again, this time finishing by pitching the ninth inning for both teams. But Lefty kept going out there every time Connie Mack called on him.

All the time Lefty was pitching, he was also eating. For the first time in his life, he gained weight, eventually 20 pounds. "They were giving us two banquets every morning, then you'd go out and play a game and there'd be two more banquets before you'd get to bed," Lefty said. "And you had to eat if you wanted to be polite. ... Everybody is polite in Japan. I guess I was too darned polite for my own good."

The tour ended with as much pomp as it had begun, and after one last banquet the Americans sailed from Yokohama on Dec. 2. The event had been such a success that Matsutaro Shoriki kept the All-Nippon team together and renamed them the Tokyo Yomiuri Giants, who exist to this day. The following year Shoriki organized a league, and professional baseball in Japan was born.

The U.S. team, meanwhile, headed south for stops in Shanghai, Hong Kong and Manila, where it would play four more games. Manila presented a new brand of exotica, as Lefty noted: "The steward told us today that in the Philippines they eat dog. They starve it for days and then feed it rice and roast it alive. Claire Ruth won't eat meat in Manila. And I'll never forget the hotel. I woke up and heard a noise like squack-squack, something like a frog. I jumped out of bed and turned on the lights, and on the ceiling were lizards about six inches long. I was afraid of them, so I ran into the bathroom and soaked a towel in water and began heaving it at the ceiling. I hit about three of them. Next morning I told the hotel manager about it, and he said not to tell anybody else [the lizards were dead] or nobody would want my room, because the lizards killed the mosquitoes."

Most of the group then headed home. Some members of the tour, however, decided to make other arrangements. The Ruths, the Hilleriches and the Gomezes decided, strictly on impulse, to head south to Java, Bali and Sumatra and from there to continue west until they had circled the globe. They saw one-legged dancers in Bali and the world's largest orangutan in Surabaya. They danced on Christmas Day at the Des Indes Hotel in Java, drank at Raffles in Singapore, visited the sultan's home in Sumatra (complete with 10 wives, one of whom was a German) and visited the temples of various Eastern religions. They steamed across the Bay of Bengal to Ceylon, then through the Arabian Sea to the Gulf of Aden, the Red Sea and the Suez Canal en route to Marseilles. Passage through the canal took 12 hours, past camels and Mount Sinai and the Biblical location where the Red Sea parted.

"June and I were like schoolchildren let loose to run around the world," Lefty said, summing up the entire adventure. "We were in our 20s, and there was nothing but laughter every moment of every day. Because our trip took place before airplane travel and computers brought the world to your backdoor, June and I were fortunate to experience life in these countries as it had been lived for centuries."