Vile Penn State case a lesson for naïve fans, power programs

Amid the media firestorm that followed the release of the Jerry Sandusky Grand Jury report last November -- when it seemed like every columnist, blogger and talking head in the country was racing to see who could get the angriest; when Joe Paterno morphed from coaching legend to devil incarnate in the course of a bye week; when all manner of Penn State cover-up allegations skipped straight past conspiracy theory to universally accepted fact -- I took a cautious stance. While the charges against Sandusky were indisputably vile, the details of how Paterno and Penn State administrators handled Sandusky over the years were still vague and incomplete. Surely more information would provide some sensible explanation for why Sandusky was not apprehended sooner; surely the leaders of an esteemed university could not be so nakedly negligent and sinister.

The facts came out Thursday in the meticulously sourced Freeh Report, and boy do I feel naïve. It turns out what really happened was even worse than the most caustic cynics could have imagined. As Freeh wrote in his summary: "The most powerful men at Penn State failed to take any steps for 14 years to protect the children who Sandusky victimized. Messrs. Spanier, Schultz, Paterno and Curley never demonstrated, through actions or words, any concern for the safety and well-being of Sandusky's victims until after Sandusky's arrest."

I particularly feel like a dupe because, as someone who covers the sport for a living, I have a front-row seat to the warped and intoxicating power football can hold over a university. As a result of that power, disastrous consequences can ensue.

Freeh hammers that point home throughout his report, but the most damning passage comes on page 65. As you may recall from the Sandusky trial, a Penn State janitor witnessed a Sandusky rape and told his colleague about it, but neither man reported it to police. That colleague told Freeh investigators that "reporting the incident 'would have been like going against the President of the United States in my eyes.' 'I know Paterno has so much power, if he wanted to get rid of someone, I would have been gone.' He explained 'football runs this university' and said the University would have closed ranks to protect the football program at all costs."

Penn State's was a particularly insular program, secluded not just from the rest of the campus but from the rest of the country (good luck finding a direct flight to State College on a game weekend). Its coach, as a result of sheer longevity, was the most powerful in the country, even into his 70s and 80s. Perhaps it's no coincidence that the biggest college scandal of our time took place at this particular university. But the lesson is that something this sinister could easily happen on any campus where "football runs the university." In fact, the circumstances are riper now than ever.

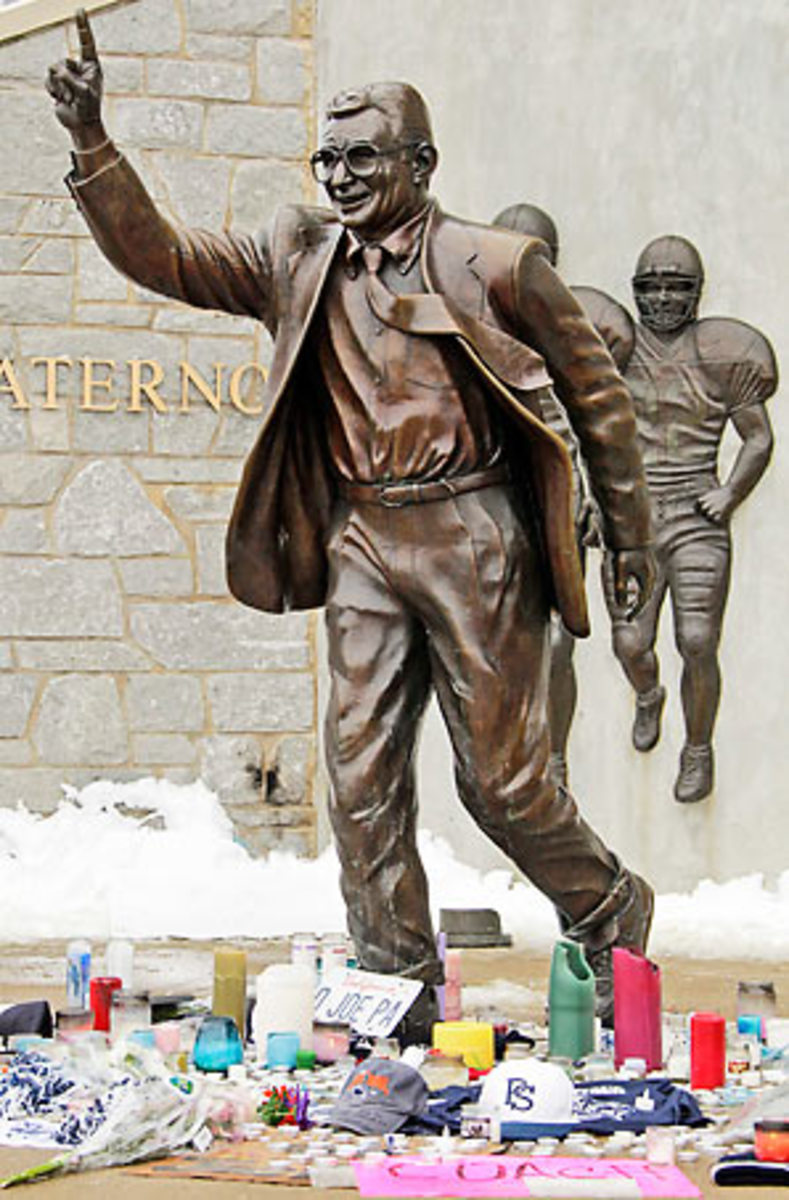

All around the country, schools are building football fortresses that make Penn State's now-infamous Lasch Building seem like a studio apartment. They are shifting more athletic administrators out of their traditional campus offices and into these autonomous palaces. They are paying head coaches $5 million a year and giving them unchecked freedom to make decisions about more than just Xs and Os. (See: the Bobby Petrino staff hiring process.) Like with Paterno, they're building statues of active coaches. And with conference television contracts now skyrocketing into the billions and the schools set to make even more money from the forthcoming BCS playoff, the pressure to maintain a high-performing football program grows exponentially.

Those same universities and programs deal regularly with potential crises that might drive a self-protecting coach or kowtowing athletic director to try to "avoid publicity issues," which is the explanation Tim Curley gave a Second Mile executive for why Sandusky would no longer be allowed to bring kids on campus (as opposed to, you know, protecting them from being raped). It's not just the universities that play on national television every week. Just look at the recent scandal that befell Montana.

Because it's an FCS school, the story didn't garner nearly the same attention as Penn State's, but the details are no less disturbing. The Grizzlies' head coach and AD were recently fired, and the Department of Justice has launched an investigation following a series of suspiciously handled sexual assault allegations against football players. E-mails exposed a university vice president, Jim Foley, suggesting retaliation against an alleged victim who went public with her story and criticizing a newspaper's use of the phrase "gang rape" to describe a woman's accusation that she was drugged and sexually assaulted by four players.

There's no Freeh Report yet for Montana, which like Penn State is a traditional power at its level (two national championships, 11 playoff appearances). And like Penn State, it takes its football very seriously -- more seriously, apparently, than the plight of sexual abuse victims.

At one point the Freeh Report notes that Graham Spanier acted more vigorously to protect the campus from a rogue agent who jeopardized star running back Curtis Enis' eligibility for the 1997 Citrus Bowl than from Sandusky, who, astoundingly, continued attending Penn State games in a luxury box right up until the weekend before his arrest. Many of us can relate to that unfortunate dichotomy. Just a year ago we were worked into a frenzy over discounted tattoos at Ohio State and free yacht rides at Miami. Those "scandals" now seem so trivial compared to the human tragedy Penn State's leaders enabled.

And yet, even today, a great many are still clamoring for the NCAA to wield its own justice in the Penn State case, as if the gravity of the situation won't fully hit home until Mark Emmert does something about it. But by falling entirely outside the NCAA's considerable bylaws, this case illustrates an underlying frustration: Who exactly is monitoring these powerful institutions?

This isn't the NFL, where Roger Goodell has unilateral authority to investigate and discipline teams, coaches and players. The media try to fill that role, but are often hampered by stonewalling or manipulative administrators (see the way Spanier, Gary Schultz and Curley carefully chose their words in those e-mails to avoid FOIA detection, a few years before PSU remarkably got itself shielded from public records laws altogether). Generally speaking, if a powerful football coach wants to keep something hush-hush -- and is smart enough not to use his university-issued cell phone or e-mail account to address a matter -- he'll often succeed. Paterno himself openly pined for the old days when the cops brought troublemaking players straight to him, thus avoiding the fuss. The Freeh Report makes me wonder how much that culture actually changed.

If anything positive can come of the Penn State scandal, it's this: Hopefully every coach, athletic director, president and administrator in the country read every page of Thursday's report and absorbed the horror of their counterparts' mistakes. Hopefully they paid particular attention to the group's 120 recommendations to avoid future such occurrences, some of which are unique to Penn State, but most of which would serve any university well.

Hopefully -- because we have little choice but to trust that in times of crisis, when our cherished universities have to make tough choices that could harm a popular sports team, the leaders will do the right thing. I, for one, am no longer naïve enough to believe they always will.