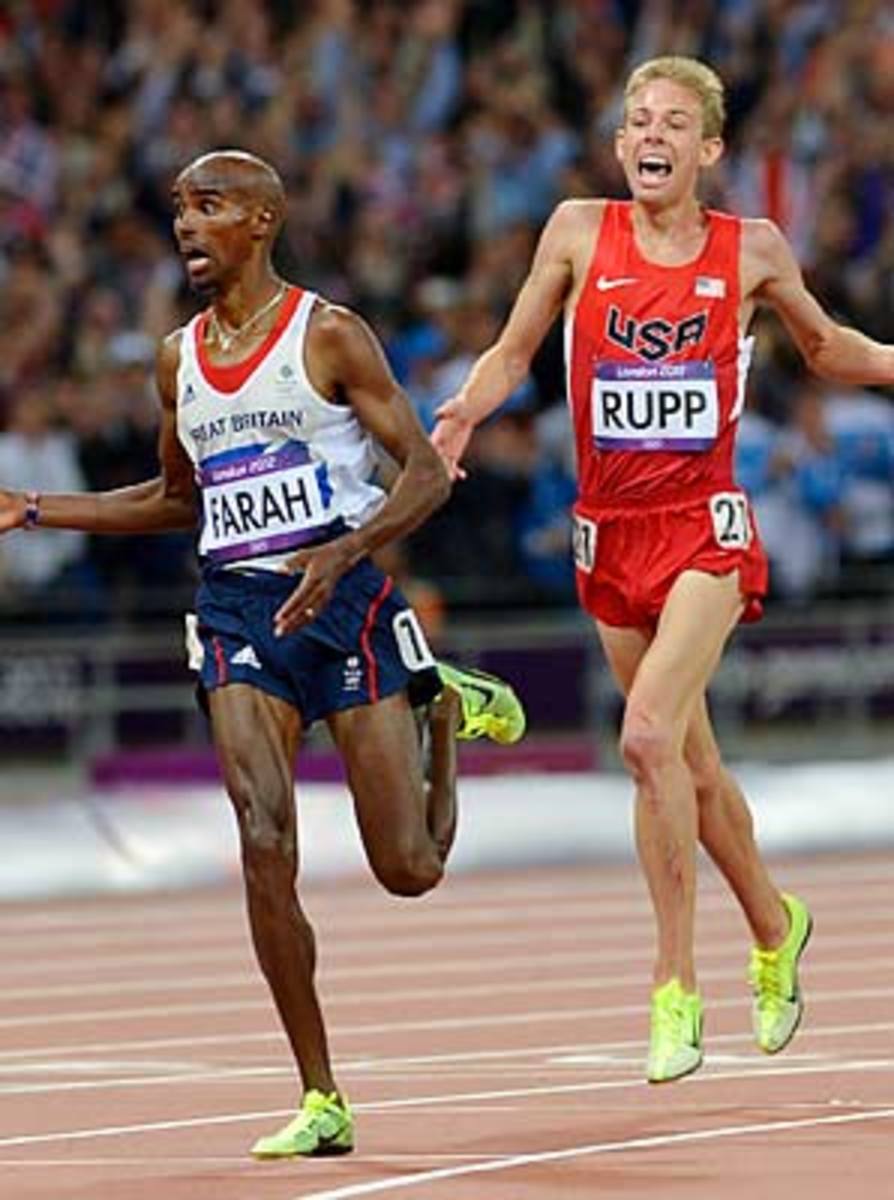

Farah, Rupp solidify brotherhood with historic finish in Olympic 10k

This was Farah's home; he had come to London from Somalia in 1991, when he was eight years old, and settled in a small ethnic community in west London. He had gone to a public high school where he first played soccer and scrapped with classmates who made fun of his language struggles, and eventually was guided to a running career that would change his life. Teachers, coaches, family members and friends enabled his greatness, and now it seemed they were all by his side, embodied by the roar. "They kept getting louder and louder,'' Farah would say later. "It just meant so much to me.''

The crowd that carried Farah was finding an emotional reserve of its own. Scarcely half an hour earlier, Farah's fellow Brit, the sainted Jessica Ennis, had clinched the gold medal in the heptathlon, rewarding a nation that seemed to treat her success as if she were every Briton's only child. And Greg Rutherford was leading the long jump and would clinch the gold medal two laps into the 10,000 meters. The night air was thick with that unique communal pride that so often moved the Olympics' home nation, and this was a truly special moment: "We're a nation that loves distance running,'' said Ian Stewart, who had beaten Steve Prefontaine for the bronze medal in the 5,000 meters at the 1972 Olympics. "That's where our heart is.''

Now they willed Farah to complete a remarkable hat trick, as he passed the finish to a sound of a clanging bell that signaled one lap to run. Farah rolled through the first turn and exploded down the backstretch, pumping his left arm slightly higher than his right, as he always does. Behind him, two-time Olympic 10,000-meter champion Keninisa Bekele, the world record holder in both the 5,000 and 10,000 meters, strained to keep contact, along with his brother, Tariku. Galen Rupp of the U.S. chased the trio into the final turn and then swung wide to pass the Bekeles. This was the race that Farah's and Rupp's coach, U.S. marathon legend Alberto Salazar, has envisioned. "You know what, fast or slow,'' he had told them, "You can outsprint anybody in this race.''

At the end of more than six miles of running, Farah ran his final 400 meters in 53.8 seconds and crossed the line as a gold medalist, with a spasm of relief and celebration. His pregnant wife, Tania, and daughter Rhianna, ran onto the track to greet him. "This is the greatest day of my life,'' he would say. Less than half a second behind him, Rupp had won the silver medal. And those medals were freighted with history: Farah's was the first by a Briton in an Olympic flat (non-steeplechase) distance race since the discontinued five-mile race in 1908. Rupp's was the first U.S. men's medal in the 10,000 meters since Billy Mills's stunning gold in 1964 and also the first in the Olympic 10,000 by an athlete not born in Africa since 1988.

Just a few short steps beyond the line, Farah turned to Rupp, 26, and they embraced. "I've been able to train with the greatest distance runner in the world,'' Rupp said afterward. "He's been an unbelievable mentor to me.'' Both will also run the 5,000 meters here, and both will be medal threats

Said Farah, "My training partner, my friend. I knew he would be there with me at the end.''

* * *

Another night, six months earlier, far from London. Farah is stretched out on a hard couch in the living room of an apartment in the foothills outside the altitude mecca of Albuquerque. Rupp is sitting at the kitchen table. Salazar is in the kitchen, pouring a glass of red wine for himself only. During this February training period, Rupp's wife, Keara, is staying at the complex. Farah's family is back at the Nike Oregon Project's home base in Portland. "I won't see my wife and daughter for five weeks,'' says Farah. "That's the hardest part. It's difficult.''

Salazar had been coaching Rupp for nearly a decade when he began working with Farah in the winter of 2011. The Salazar-Rupp arrangement had been both fabulously successful (five NCAA track titles at Oregon, one NCAA cross country championship and, at the time, three U.S. 10K track titles) and controversial. "People were saying I was using steroids when I was 15," said Rupp in a story I wrote for Sports Illustrated last February. "They'd say I'll burn out in three years. It was hurtful at times. But no regrets. Things have gone pretty well."

In the fall of 2010, Farah's management team approached Salazar and asked him to bring Farah into the Nike Oregon Project, which only became possible when Farah's adidas contract expired and he signed with Nike. Rupp was reticent, but Salazar convinced him. The two runners bonded over soccer as players (both had played when younger), fans (Rupp likes Man U. and Farah cheers for Arsenal) and Xbox devotees. They were from vastly different cultures, yet they grew close. "They're like brothers,'' said Salazar in February. And they would make each other better.

* * *

Farah nearly won two titles at the world championships of track and field last summer in Daegu, South Korea, where a close, silver medal finish in the 10,000 meters was followed by a gold medal in the 5,000. International distance running has evolved to where races almost always come down to furious sprint finishes (a trend begun in earnest by the great Ethiopian Haile Gebrselassie in the mid 1990s, and continued by Bekele). Salazar vowed that neither Farah nor Rupp would be vulnerable to a kicker. The Olympic year's training was predicated on adding more speed to careers' worth of strength and distance work. (Salazar was quick to point out that Rupp is actually a faster sprinter than Farah, but Farah's deeper well of distance training allowed him to sprint faster at the end of races. Salazar expected the gap between them to shrink over time, and it has).

They would come to London from vastly different places, Farah feeling the weight of a country and Rupp far beneath the American sports radar, which is trained on professional team sports and even at the Olympics on swimmers and gymnasts (and even in track, on Usain Bolt). On his trips to London during 2012, Farah steadfastly avoided traveling near the Olympic Stadium, so as not to summon up emotions that he would only need later. Rupp, meanwhile set meet records in winning both the 5,000 and 10,000 meters at the U.S. Olympic Trials, and in the latter he outkicked the venerable Bernard Lagat, a loud signal of things to come.

The training group, which also includes U.S. 10k Olympian Dathan Ritzenhein, convened in Park City, Utah, not long after the U.S. Trials, and then went to Font Romeu, France, another altitude hot spot at 6,000 feet, three weeks before the Games. Salazar piled on lung-searing speed work. "Mo and Galen did the same workouts,'' said Salazar, "but not together I didn't want them trying to beat on each other before the Olympics.''

On one day in France, roughly two weeks out from the 10k final, they did six 1,000-meter repeats at an average of 2:38 with just a 500-meter jog between repetitions, and then tacked on three 400-meter sprints in 52 seconds each, a workout made much more taxing by the thin air. Six days before the Games, they did an inverted ladder of three 600-meter sprints in an average of 1:36, 400 meters in 61 seconds, 300 meters in 44 seconds, 200 meters in 27 seconds and then a blazing 300 in 37 seconds flat, followed at the very end by an all-out 400 in 51 seconds. Just before leaving for London, Rupp ran a 100-meter sprint with a two-step running start in 11.03 seconds, his fastest ever. They were ready.

Upon arriving in London, Rupp ran around a park near his hotel and felt his lungs fill sweetly. "There's so much oxygen,'' he said three days before the 10,000 final. "That's a great feeling.'' Farah arrived a day later and Salazar told anyone who would listen, "We're going to win two medals.''

On Saturday night, the 10,000-meter runners were moved one call room to a closer call room, and Farah found himself filled with energy. "It was like someone gave me 10 cups of coffee,'' he said. "I was just shaking.'' He knew that Ennis and Rutherford had won gold medals and would say later, "I knew that I had to do something.''

The 10,000-meter runners walked from the tunnel as Ennis led the heptathletes on a victory walk around the track. Farah stripped off his warmup, dropped it into a clear plastic bin trackside and then walked onto the track, with a foot or two of Ennis, who was wrapped in a Union Jack. The two were in far different places, Ennis in heaven of relief and celebration and Farah in a world of nerves. They did not speak. Just before lining up, Farah and Rupp embraced.

The race unfolded like so many championship events, slowly and roughly. The first 5k was covered in a dawdling 14:05.79, only 43 seconds faster than gold medalist Tirunesh Dibaba ran the final 5K of her 10,000 24 hours earlier. It was rough. At one point, U.S. runner Matt Tegenkamp, who would finish 19th, asked Rupp if he needed Tegenkamp to create an opening for him, and when the race was done, blood trickled from a spike wound in Rupp's left shin. But the pace itself was perfect for Rupp and Farah. "I wanted it to be even slower,'' said Farah, so that it would leave him fresher to kick. Salazar had told them that the race would be won in the final 100 meters.

The tempo did not quicken until very late, but when it did it was immediate and killing. The penultimate lap was run in 61 seconds and that final lap in less than 54, 800 meters in 1:55. Unlike in Daegu, Farah did not falter. Rupp had finished 13th at the 2008 Olympics, ninth at the 2009 worlds and 7th at the 2011 worlds. He was a different runner now. "Mo is the best distance runner in the world,'' sais Salazar, "and Galen isn't very far behind him.''

When it was done, Farah carried both a flag and a giant stuffed mascot around the track in a victory lap that was appropriately momentous and a manifestly joyful. Rupp wrapped himself in a U.S. flag, elevating its colors nearly to the top of the distance-running world, climbing on the shoulder of Bob Kennedy, Meb Keflezighi and Lagat. One shared his moment with an entire nation, the other with a small world that appreciates its importance. And much more deeply, they shared it with each other.