Well-traveled Travis Wiuff guns for Bellator title and permanent home

Outside, the previous night's snowfall reached up to your knees and the biting wind nipped at any part of the body left uncovered, so prolonging the ride home on Minneapolis' icy roads was always an appetizing prospect. There wasn't much else to do during the bitter Minnesota winters anyway, so why not?

Among this group of aspiring mixed martial artists, Travis Wiuff fought two, three, sometimes four times a night in bars, community halls and other makeshift venues around the Twin Cities. In 2001, Minnesota didn't have a state athletic commission to oversee MMA fights. There was no ambulance on standby, no blood tests beforehand to catch transmitted diseases, no physician sitting ringside should something go awry. If you got hurt, you took your injuries and your gym bag home with you.

Still, the promoter wasn't at a loss for volunteers, who secretly prayed that the next guy standing across the ring from them had trained MMA less than they had.

Eleven years later, Wiuff (68-14, 1 NC) has experienced every level of MMA promotion around the world. He's fought in the Saitama Super Arena in Tokyo, home to some of the most attended MMA events in history. He's fought in a horse barn at the Rochester Fairgrounds.

On Friday, he lands somewhere in-between, facing Slovakian prospect Attila Vegh (27-4-2) in Bellator Fighting Championships lightweight tournament finals in Tunica, Miss. (MTV2, 8 p.m. ET/PT).

For Wiuff, the fight is about personal redemption. Twice Wiuff has clawed his way up the ranks into the UFC and both times he's come up empty. Winning Bellator's tournament guarantees him a title bout against divisional champion Christian M'Pumbu, who Wiuff already bested in a non-title bout last October. And becoming a champion for the fast-rising, Viacom-owned promotion -- which should make a big splash when it moves to Spike TV in 2013 -- will give the soft-spoken Wiuff something he's quietly searched for his entire MMA career -- a fighting home.

In 2001, following two years at Rochester Community and Technical College, a disenchanted Wiuff dropped out of Minnesota State University Mankato just a year shy of his law enforcement degree and moved back home with his parents. The law enforcement program wasn't what he'd expected, said Wiuff, and he didn't want to end up like the officers he'd met, with "attitudes and chips on their shoulders."

Wiuff didn't have to become a city cop, but he had to become something.

That summer, he walked into a Twin Cities bar in the hopes of getting picked up as a bouncer. Instead, a bald, heavily muscled stranger walked up to Wiuff and offered him a fight.

Brad Kohler, famous for knocking out Steve Judson with a blistering right that sent him head-first into the canvas at UFC 22 in 1999, promoted shows monthly in venues around the Twin Cities. Kohler probably took one look at Wiuff's athletic 6-foot-2, 285-pound build and knew he had someone who, at the very least, could hold his own in a fight.

Wiuff, a two-time junior All-America in wrestling, politely declined Kohler's offer and its follow-up to visit Kohler's Minneapolis gym the next day. "I'd never thrown a punch in my life," said Wiuff, who'd never been messed with as a child because of his intimidating size. "I'd never been in a fight."

But as Wiuff made the hour-long drive home to Owatonna still jobless, he reconsidered his options. "I was 21 and I'd be the first to admit that I didn't have a lot going for me."

Wiuff showed up at Kohler's gym the next day and was put through some drills. At the end, Kohler again offered Wiuff a fight in his Ultimate Wrestling show the very next day.

Wiuff's wrestling experience, size, strength and natural calmness carried him easily through his first fights. Not realizing guys actually got paid to do this, Wiuff didn't ask Kohler for payment at first and Kohler didn't volunteer it.

With his blonde, buzz-cut hair and hulking physique, Wiuff looked a bit like WWE superstar Brock Lesnar and he quickly became a local attraction. To keep his emerging star coming back, Kohler threw Wiuff $100 or gas money or sometimes a meal. When Wiuff's car gave out, Kohler got him a beat-up 1989 Corsica that he started with a twist of a screwdriver jammed into the ignition slot.

Like a scene out of a movie, Wiuff would drill an unsuspecting opponent into the canvas and the Svengali promoter would then jump into the ring to offer $1,000 to anyone willing to go with the wrestler next and beat him. Nobody ever won. At the end of the night, Kohler's team would pack up the ring and move on to the next town to start all over again the next weekend.

"It was a real traveling circus," said Wiuff, who estimates he fought 15-20 times in the first year alone. "One time I fought this big biker and he wore a big belt buckle and a pair of cowboy boots into the ring. I asked that he take them off."

Wiuff had no illusions about those earlier days. "Most of the guys I fought were zero-level competition and I wasn't much better," he said. "I was just a big, strong wrestler."

The young fighter got his first break in a four-man heavyweight tournament for Extreme Challenge, a popular Iowa-based promotion run by well-connected manager Monte Cox. In his first bout, Wiuff somehow managed to knock out future UFC staple Keith Jardine in six seconds. Wiuff lost in the finals, but Cox had taken notice. When an opening came up in Superbrawl's 16-man tournament in Hawaii, Wiuff got the call. Wiuff's quarterfinal opponent dropped out before the event, but he didn't mind.

"I got $500 and a free trip to Hawaii. I was stoked," recalls Wiuff, who'd never left Minnesota before. "I was giving autographs to little Hawaiian kids. I couldn't believe it."

Following Superbrawl, Wiuff realized he'd outgrown Kohler's Minnesota circuit and there were greener pastures to be had. He didn't have to wait long for his next opportunity. In July 2002, Cox secured Wiuff a replacement slot against Vladimir Matyushenko at UFC 40 in Las Vegas. With only eight months of legitimate training under his belt, Wiuff would be a UFC veteran.

Cox, who became Wiuff's manager, hastily shipped his new client to Pat Miletich's training academy in Davenport, Iowa, for some last-minute cramming.

"After about three days, I remember Miletich saying he couldn't believe I was fighting in the UFC in a week," said Wiuff. "He was very honest about it. But nobody turned down the UFC."

Las Vegas was wonderful and overwhelming and scary all at the same time. Wiuff had never fought for a promotion that flew its fighters in five days before a show, offered daily food stipends and held public press conferences.

"I was unfamiliar with everything and I just wanted to get it over with," said Wiuff.

Wiuff got his wish, as it took the seasoned Belarusian Matyushenko only four minutes to coax out a submission from punches. Still, Wiuff made $5,000 in defeat, a pretty penny for a single guy who lived life simply in Minnesota.

That little taste of the big time sparked Wiuff's interest in legitimate training. Wiuff found his first coach, Dave Menne, about an hour and a half away from Owatonna. Menne, the UFC's first middleweight champion in 2002, taught Wiuff submissions and how to throw a punch properly.

"Dave was quiet, but a funny guy if you could understand the mumbling coming out of his mouth," said Wiuff. "In the three years I trained with him, we probably never had a conversation that was more than 10 minutes long."

Under Menne's tutelage, Wiuff grew as a fighter quickly and gave Cox a lot more to work with. In 2004, Wiuff believes he fought 22 times; many of those bouts unrecorded. As a UFC veteran (something local promoters could proudly display on their advertising), Wiuff made anywhere from $2,000 to 5,000 a fight, more than enough to keep his 1972 Ford running.

By 2005, Wiuff amassed a (recorded) 20-fight win streak, which earned him another stab at the UFC. The decision was made that Wiuff would cut down to light heavyweight (205 pounds), which proved disadvantageous against opponent Renato "Babalu" Sobral. Much quicker than the heavy fighters Wiuff had faced his entire career, the Brazilian jiu-jitsu black belt submitted Wiuff 24 seconds into the second round at UFC 52.

Still, Wiuff kept plugging along. In 2006, he moved to Utah to study under MMA grappling legend Jeremy Horn and later rejoined Miletich to become the light heavyweight member of his Silverbacks team in the International Fight League, a short-lived promotion that used a team format that never caught on with fans.

In 2008, Wiuff won the much ridiculed Yamma Pit Fighting's first and last heavyweight tournament, taking out former UFC champion Ricco Rodriguez in the process. Grabbing his $25,000 grand prize, Wiuff laughed all the way to the bank.

Winning Yamma got Wiuff his break into Japan, where a couple of promotions were operating moderately-sized events in the void left by Pride Fighting Championships after it had been bought and essentially shut down by the UFC owners Zuffa LLC.

In June 2008, Wiuff recorded one of the bigger victories of his career when he shockingly knocked out hard-headed brawler Kazuyuki Fujita in his Sengoku debut in Tokyo.

"I think I was the most shocked person in the Saitama Arena," said Wiuff, who made a career-high $50,000 for the upset victory. "I knocked Fujita out with a jab."

When Japan's MMA market dried up, Wiuff was back to his old stomping grounds, taking whatever fights Cox could muster up for him with pleasure.

"He'll fight on a week's notice. He'll fight on a day's notice," said Cox, "which makes him a manager's dream in that respect. On the other hand, I'll get Travis four fights in five weeks and he'll call me up in week six asking me when his next fight is."

Over time, Wiuff's experience and record (which could easily total over 100 fights) has made it more difficult to book him, said Cox. In 2011, as the world continued its recession spiral, Wiuff fought only twice, and had to pick up odd jobs to support himself and his five-year-old daughter, Ashley.

In late 2011, Bellator matched Wiuff against its light heavyweight champion M'Pumbu in a non-title tilt. When Wiuff won the fight via decision, Bellator had no choice but to place him in the tournament with the opportunity to earn $100,000 over three fights.

"I'm happy Bellator gave him a chance," said Cox. "I think people can have a preconceived idea of who they think Travis is. He's lost a couple of times in the UFC, so people think he's not at that level. But he's improved tremendously over time. It just took 10 years to do it."

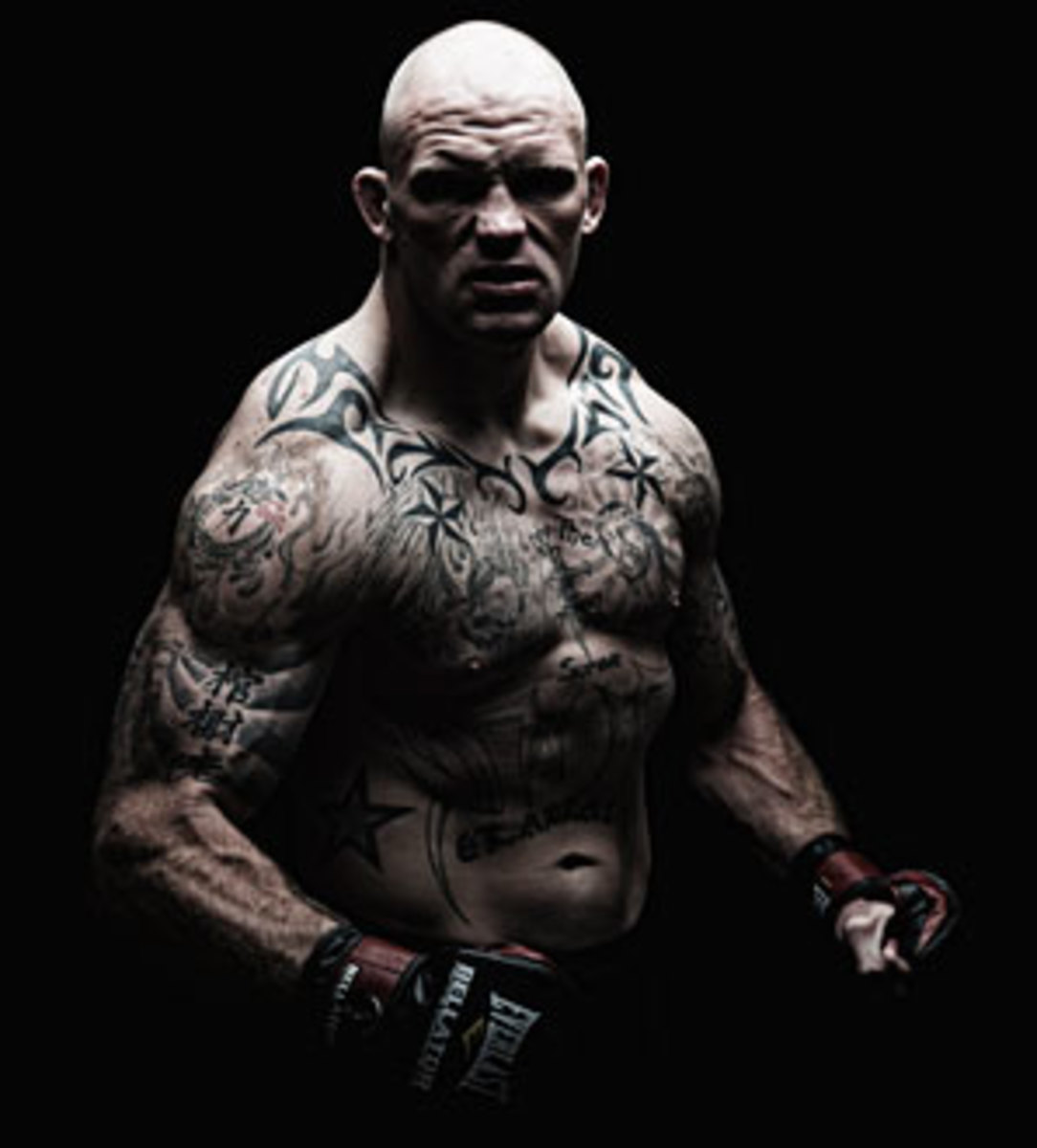

Bellator has billed Wiuff as the biggest light heavyweight fighter in the world, a marketing ploy that just might be true. Wiuff, who walks around at 250 pounds, said he should weigh about 225 the night before weigh-ins before donning his plastic suit and climbing aboard the stationary bike. (Wiuff doesn't use the sauna to cut weight.)

Wiuff might also be one of the healthiest 34-year-old fighters the sport has ever seen. He claims to have never been sick a day in his life, has never had a headache, has never smoked and hasn't touched a drop of alcohol his entire life.

Though Wiuff has been one of his steadiest clients for the last decade, Cox said the tournament has brought up never-before-seen emotions for the respectful, introverted Wiuff. After his semifinal win in June, Wiuff uncharacteristically erupted for the crowd, goading champion M'Pumbu that he'd be coming for him.

"Bellator has put a little fire in him," said Cox. "It feels like a redemption. He's showing people that he still belongs, and he does."