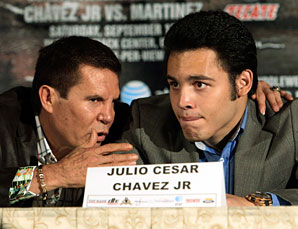

Legendary father, celebrated trainer have lent to rise of Chavez

It was Chavez Sr. who first piqued Junior's interest in boxing or, more accurately, his spectacular success in the ring. Junior says he was two years old when he first started attending Senior's fights and "didn't miss more than a few" thereafter. "I got addicted to boxing," Junior said. "I used to watch it all day long."

It was Roach who taught Chavez Jr. how to fight. Chavez Jr. was undefeated when he came to Roach's Wild Card gym in 2010. But his record was inflated by anonymous and overmatched opponents, and he had a reputation for laziness in the gym. Under Roach's guidance, the workout habits changed, the skills were polished, and today Chavez Jr. ranks as one of the best 160 pounders in the world.

"When I came to Freddie, he started showing me things I never thought about," Chavez Jr. said. "I always thought I was training, but when I met Freddie it was a whole different level of getting ready for fights."

*****

Whenever Chavez Jr. trains, Roach and Chavez Sr. are usually nearby, strategizing, offering advice. Too many cooks in the kitchen? Perhaps, if Chavez Sr. weren't more concerned about rebuilding a relationship with his son than guiding his career.

For years Junior idolized Senior, worshipped the very ground he walked on. But when Chavez Sr. retired in 2005, drugs and alcohol consumed him. He fell to the depths, and Junior witnessed every crash along the way. Many nights Junior would be at home asleep and Senior would stumble into his room in the early morning and insist on talking to his son for hours.

"He was in no shape to speak to me," Chavez Jr. said. "It's a horrible experience to go through something like that. You don't know what to think, you don't know what to do. You get frustrated. It's like a torture every day, seeing someone that you love go through that."

Love gave way to pity and eventually fear. When someone called about his father, Junior assumed it was to tell him he was dead.

"I was expecting that call every time," Chavez Jr. said. "It was always on my mind."

In August 2010, Junior resolved to take action. One afternoon, in Tijuana, Senior told him he felt sick. Junior convinced him to go to the hospital, where a doctor put him under anesthesia and transported him to a rehab clinic. When Senior awoke, he was furious. He cursed his son. He threatened to disown him. He expected Junior to cave and let him leave after a few weeks. He stayed six months.

Chavez Sr. is clean and sober now, and the bond between father and son has begun to tighten again. Yet while Junior has welcomed Senior into his camp, it's clear whose advice he follows. "Freddie teaches me the strategy," Chavez Jr. said. "My dad is there for support. I listen to both, but Freddie is the one who trains me."

Roach understands the delicate balance in boxing between father and son. His own father trained him for years before he delivered him to Eddie Futch, and Roach saw how painful it was for him to do it. "It's a manly thing to do to give up your son," Roach said. When Roach trained Peter Manfredo, he always knew Manfredo's father wanted to run the show. "He would let me take the lead," Roach said. "But I knew he wanted to be the guy."

Roach and Chavez Sr. talk daily, and Roach says he welcomes his opinion. Recently, Chavez Sr. advised Roach to emphasize a one-two-hook combination, believing Martinez, from his southpaw stance, is open to the shot. Roach agreed

Chavez Jr. should hook but said he preferred to lead with the right hand because Martinez counters the jab so well. When Chavez Sr. complained that Junior should be more active, Roach explained that if Chavez throws more than three straight punches without moving to the side, the quicker Martinez will have more opportunities to counter.

"He doesn't disagree with me every time," Roach said. "He will listen. It's a good relationship."

Chavez Sr. has no plans to someday supplant Roach, either. The emotion of training his son is too overwhelming. When Junior fights, Senior often bounces back and forth from his corner, bellowing advice in his ear. "I tell him, if you're going to work the corner, work the corner," Chavez Jr. said. "But he can't. There are too many feelings."

During this camp, Senior grew frustrated by his son's quirky training habits, eventually disappearing back to Mexico for a day to cool off. "He came back much calmer," Roach said. "He said to me, 'Freddie you have to yell at him, I can't.' He doesn't want to be the bad guy."

In a way, the relationship between father and trainer, trainer and fighter, father and son is perfect for Chavez Jr. He has the instincts of his father, gifts woven into his DNA. "I feel it in the ring," Chavez Jr. said. "That style, the schooling, everything I ever saw from him. You can't help it. It's in the genes. It just comes out." And in Roach he has a brilliant teacher and strategist, a mentor he trusts implicitly.

Indeed, two years removed from haunting uncertainty, Julio Cesar Chavez Jr. appears to have everything figured out.