Inside story: The 63-yard field goal

In the latest edition of Sports Illustrated, available on tablets Oct. 24 and on newsstands Oct. 25, Tim Layden looks at the cult of the 63-yard field goal in the NFL. The following is an inside glimpse from Layden at the making of the story.

Get Sports Illustrated All Access and buy the digital version of the magazine here.

This week's edition of Sports Illustrated includes a story that I wrote on the cult of the 63-yard field goal in the NFL. Like the best of stories, it was a piece that took root a very long time ago and then dragged me to places I didn't expect to be taken.

From a practical standpoint, the story was born during an early September content brainstorming session that I joined in SI's New York offices, along with assistant managing editor Mark Mravic and associate editor Adam Duerson. This is one of those sessions where writers and editors bat around possible story ideas before dismissing most of them and settling on a few. Of those assigned in such sessions, only some will be executed, as teams falter, players get injured or news overrides what seemed like smart ideas a month earlier.

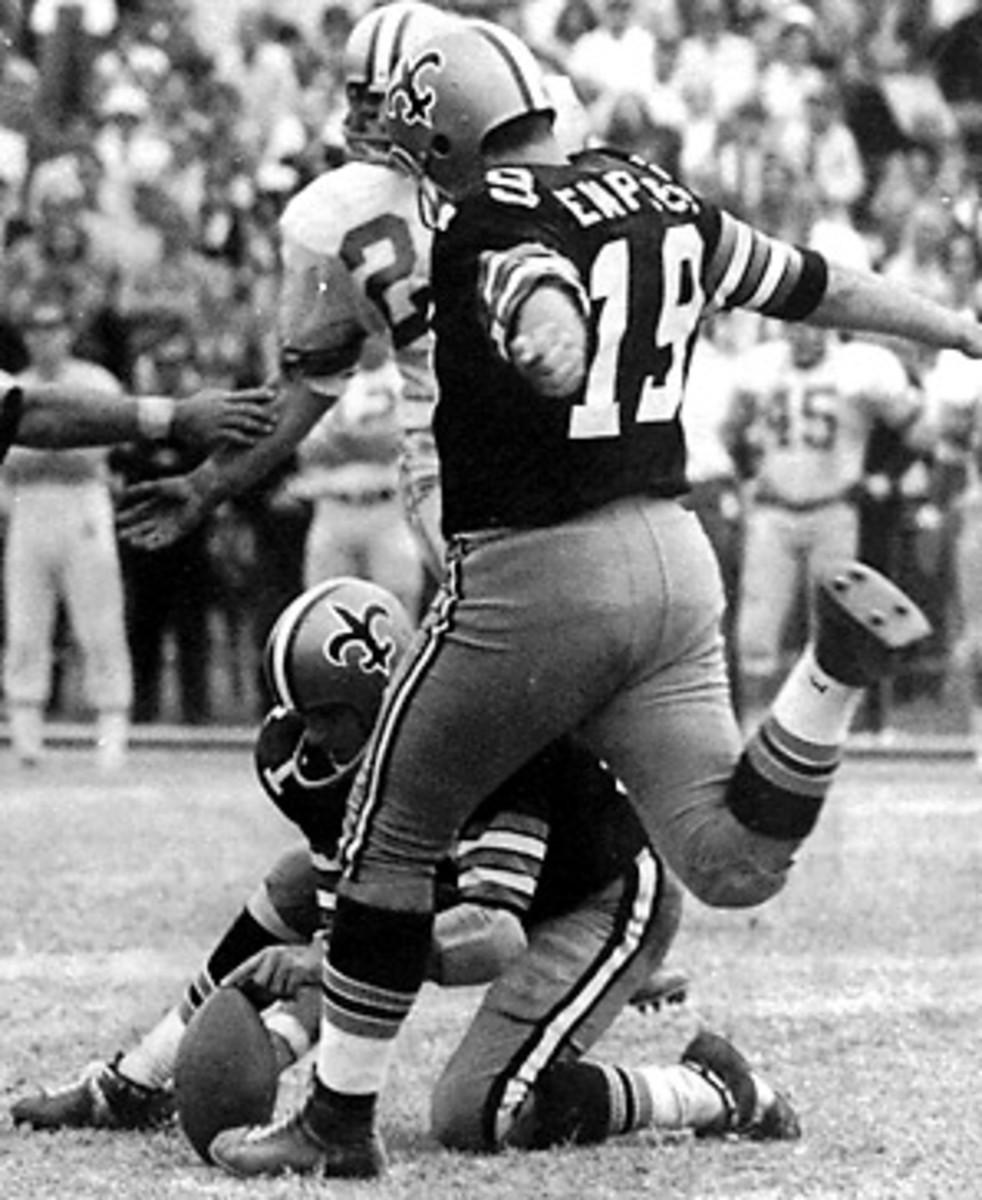

At this moment, I don't recall how the subject of long field goals was raised. A lot of ideas get brought up for discussion, including a lot of bad ones. I do remember being instantly struck by the possibility of reporting something centered on the No. 63. That's the part of the story that goes way back. I was a 14-year-old high school freshman when Tom Dempsey first kicked a 63-yard-field goal, on the first weekend in November in 1970. I was in my living room watching NFL games with my father (with my right arm in a sling, healing a broken collarbone suffered in a high school game) when the Dempsey highlight came up. Long field goals have become common, but at the time, 50 yards was long and the NFL record was 56 yards, set 17 years earlier. Dempsey was an instant statistical outlier. The fact that he did it with half a right foot elevated it to the level of football mythology, where it has remained.

Kickers have become vastly better in the 40-plus years since Dempsey's boot, but his record had been only tied at the time of our ideas session, by Jason Elam in 1998 and by Sebastian Janikowski in 2011. What was it about 63 yards? What was it about the people who shared the record? (Because it is people who make stories, not numbers.) It seemed worth a shot.

I had talked briefly with Dempsey three years ago while reporting a piece on the historic futility of the Saints' franchise before the team's victory over the Colts in Super Bowl XLIV. So I called his cell number. No answer. No callback. I emailed him. Crickets. I did some cursory research on Elam and found that he had not only written four spy novels, but also moved to Alaska with his family, where he is an avid outdoorsman. Promising. I secured a phone number for Elam and called. Also no answer. Also no callback.

It went on like this for a couple weeks, with radio silence, while I worked on other projects. And on the first weekend of the NFL season, 14-year veteran kicker David Akers became the fourth man to convert a 63-yarder. That's OK. As long as it's not 64, it preserves the odd sanctity of the number and keeps the story alive. Although the story was barely breathing at this point.

One afternoon in late September, I was walking down a street in Albany, N.Y., where I had spent the day doing research on another, wholly unrelated story. I pulled out my phone and tried Dempsey for about the 25th time, expecting voicemail and no callback. Instead, Dempsey answered. We talked and he agreed to meet with me the following week in New Orleans, a visit that would send the magazine story about long field goals in another direction altogether: Richer, sadder, more bittersweet. A story about a man's life and the tether that a single moment can provide.

That same evening, as I drove home, Elam called my cell. When it rains, it pours. Reporting is like that. It turns out that Elam had been deep in the Alaskan bush for a week, with no Internet or cell service, and was just now coming out and returning calls. Two weeks later I would be driving along the Kenai Peninsula with SI photographer/videographer Bill Frakes and his assistant, Laura Heald, witnessing some of the most breathtaking scenery I've ever seen, and ultimately meeting an ex-football player whose life has very little to do with football.

So there would be a story after all. And it would be better than I had hoped. But there was one other problem: In order for the magazine story to survive as conceived and reported, we needed for the record to remain alive until publication. That's how I found myself sitting in a scratchy chair on a concourse at an airport in Rochester, N.Y., on the afternoon of Sunday, Oct. 14. On the previous day, I had met with Olympic sprinter Usain Bolt in New York, and then flown to Rochester to meet up with the rest of my family for a function at my son's college. From Rochester, I would fly to Alaska to meet Elam.

But it was Sunday, and that meant another day of hoping that nobody kicked a 64-yarder. There were no televisions at the airport, so I was following games on my phone and laptop, when, shortly after 4 p.m., a text message popped up. It was from Mravic:

Mravic: "Zuerlein lining up for 66yd FG"

Layden: [Unprintable] (Rams rookie Greg Zuerlein had already kicked 60- and 58-yard field goals in the same game. This was dangerous).

Mravic: "JUST misses. Plenty of distance"

Layden: [Unprintable. Hyperventilating].

We arrived in Alaska that night and I returned home on an overnight flight that arrived on Wednesday morning. (I talked to Zuerlein from my Anchorage hotel room on Tuesday, to include him in the piece. The story was filed to SI on Saturday, Oct. 20, which only left me to wait out last Sunday's games. I was watching the Patriots and Jets in OT when Mravic -- doom-peddler -- called my cell to warn that Janikowski was lining up for a 64-yarder. As I staved off another heart attack, the kick fell short.

The record -- and the story --- remained alive. (Available on tablets Oct. 24 and on newsstands Oct. 25.)