Devoid of pretense, Leyland takes pride in keeping things simple

Behind the dugout at old Tiger Stadium, just out of public view, was a toilet, a decrepit thing in a decrepit ballpark. If anything truly could be said to reek of history it was that porcelain object, which for decades saw great men going, going -- but now, alas, it's gone.

That toilet is one of the first things that comes to my mind whenever the Tigers seize the spotlight, along with the Old English D on their caps, a logo rivaled in the ancient typography of baseball only by the Yankees' interlocking NY and the alphabetical three-way of the Cardinals' STL.

When the Tigers last won the World Series, in 1984, skipper Sparky Anderson would contemplatively smoke a pipe in front of that dugout lav, the white smoke issuing as it does from the Vatican when a pope gets elected. (Sparky once got Pope John Paul II to autograph an official American League baseball for him, His Holiness instinctively knowing to sign on the sweet spot.)

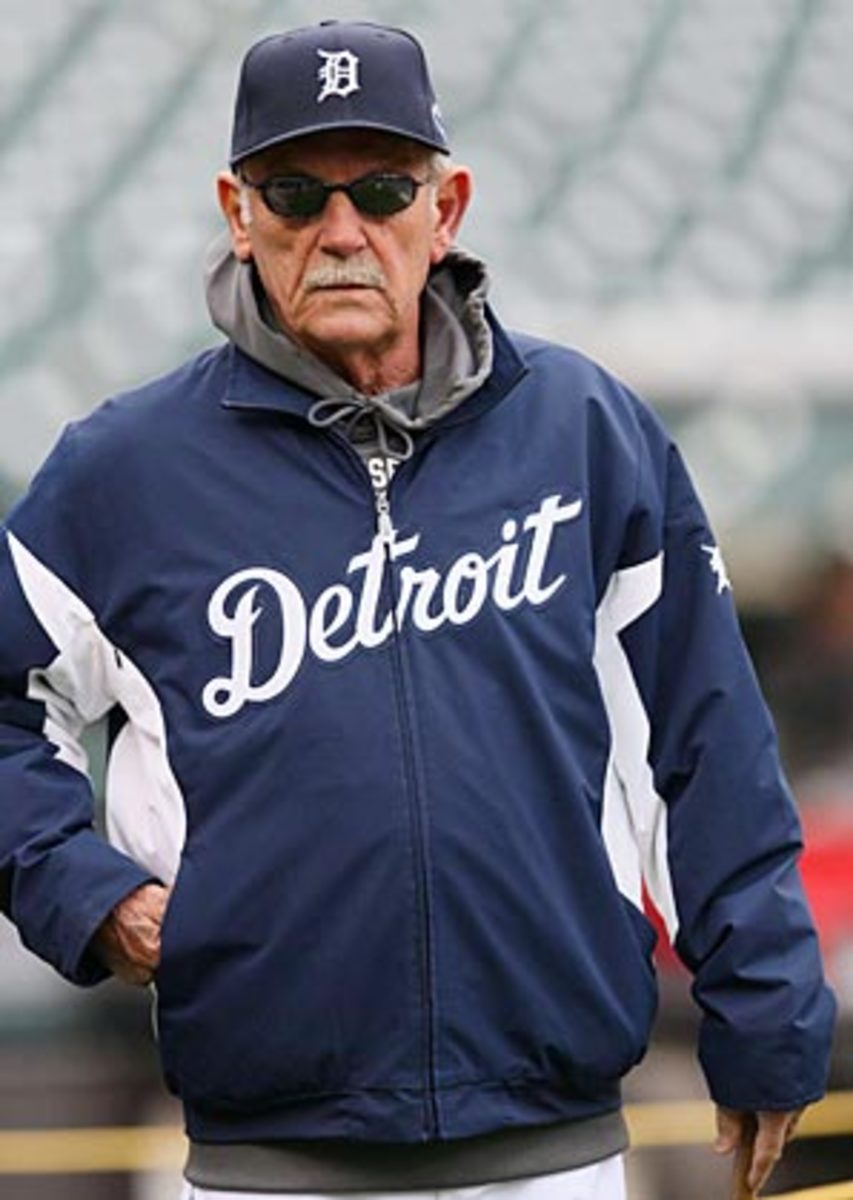

Twenty-eight years later, Jim Leyland fires up heaters at Comerica Park, but otherwise not much has changed at the Tigers' helm: The team still has a skinny white-haired wise man at the wheel, a manager entirely devoid of pretension.

Sparky would not have been impressed that the team's Gothic D is now tattooed to the right forearms of Eminem and Kid Rock. "The word celebrity and the word VIP?" he once said to me. "I die laughing when I get a letter marked VIP. It says call this number to say whether you're coming or not. I don't wanna go to the White House. I don't wanna go nowhere. Show-business people, that don't thrill me."

Likewise, I once followed Leyland in his Chrysler sedan to his modest home in suburban Pittsburgh when he managed the Pirates. "I could never be a slave to a $600,000 house," he made a point of telling me. He was 48 at the time, and his 15-month-old son, Patrick, played in the next room, and his wife, Katie, was pregnant with their daughter, Kellie.

These are the only two men to manage the Tigers for seven or more consecutive seasons since Hughie Jennings did so a century ago, and the two are remarkably similar in outlook. Both Sparky and Leyland were grateful for (and embarrassed by) the extraordinary perks of their jobs. "You're spoiled in the major leagues, let's face it," Sparky said. "Phil Niekro put it best. They asked him why he continued to play on and on all those years and he said, 'Nobody ever gives you meal money in real life.' "

Leyland, likewise, found it scarcely believable that multi-million-dollar contracts were supplemented by meal money. Twenty years ago, when his Pirates lost a heartbreaking Game 7 of the NLCS to the Braves, he was paid $9,000 in meal money that season. "When I made $400 a month, I thought I was the richest son of a bitch you ever saw," he told me. "I always had a buck in my pocket and a pack of cigarettes. My dad always said, 'He's not gonna amount to nothin', because you give him a buck and a pack of cigarettes, and he's the happiest son of a bitch I've ever seen in my life.' Well, now I make a lot more bucks. And not a damn thing has changed."

As players, Sparky and Leyland were career minor leaguers with a single season of big-league baseball between them. Both became used to -- and got a charge from -- seeing other people happy. It's a good trait to have as a World Series-winning manager, whose job is to watch from a distance as the players celebrate.

Leyland loved that his mom, Veronica, loved the TV close-ups she got in the stands when the Pirates were in the playoffs. "She was happier than a hot hog in a cool mud puddle," Leyland said. "All her friends back home [in Ohio] saw her. And, I mean, that's a thrill. And it thrills me for my mom."

Sparky, meanwhile, would visit Henry Ford Hospital in Detroit every week that the Tigers played at home, a weekly reminder of his enormous good luck. "You and me, we wake up tomorrow, what's our biggest problem?" he asked me. "You might have a few bills? I might have a loss?" He shook his head and thought of a child he'd seen who was undergoing a skin graft. "People feel bad for a baseball player having a bad year? Our values are so messed up it's unbelievable."

They managed the Tigers for 22 of the last 33 seasons: Sparky won the club's last World Series, 28 years ago, and Leyland may win the next, within a week. Both could look grizzled and ulcerated -- Leyland's stress is contagious through the TV; he makes even neutral viewers vicariously anxious. But that's not what ties the two skippers together. It's not the Gothic D, either, or the signature smoking or even the serial success.

It's this: Both knew that a life in baseball is a stroke of luck. "When I'm here," Sparky said of the ballpark, "I'm home."

"The Number One most fortunate thing in my life," Leyland said, "is I've made a living doing what I loved most as a boy."

That was nearly 20 years ago, to say nothing of several millions dollars, and two more managerial stops, and a World Series title with the Marlins. Leyland is 67 now, and his 15-month-old son just turned 21. For the last three seasons Pat Leyland has been a catcher/first baseman/DH in the Tigers' system.

Sparky, meanwhile, departed this Earth three days after the conclusion of the 2010 World Series, won by the San Francisco Giants, the same Giants who are the Tigers' World Series opponent this week, when Leyland will be in frequent tight close-up, jonesing for a smoke, for all of America to see.

But I won't be seeing any of that. I'll be seeing Leyland, as I always do, all those years ago in Pittsburgh, in his normal house, in the winter, with an infant in the next room, and him saying: "Here I am, a little Double A backup catcher, and, Christ, I'm the manager! I mean, it's hard to believe, you know? I'm seeing history and I'm thinking: [Expletive], I'm here, I'm in uniform, I'm in this dugout -- what in the hell is going on here?"