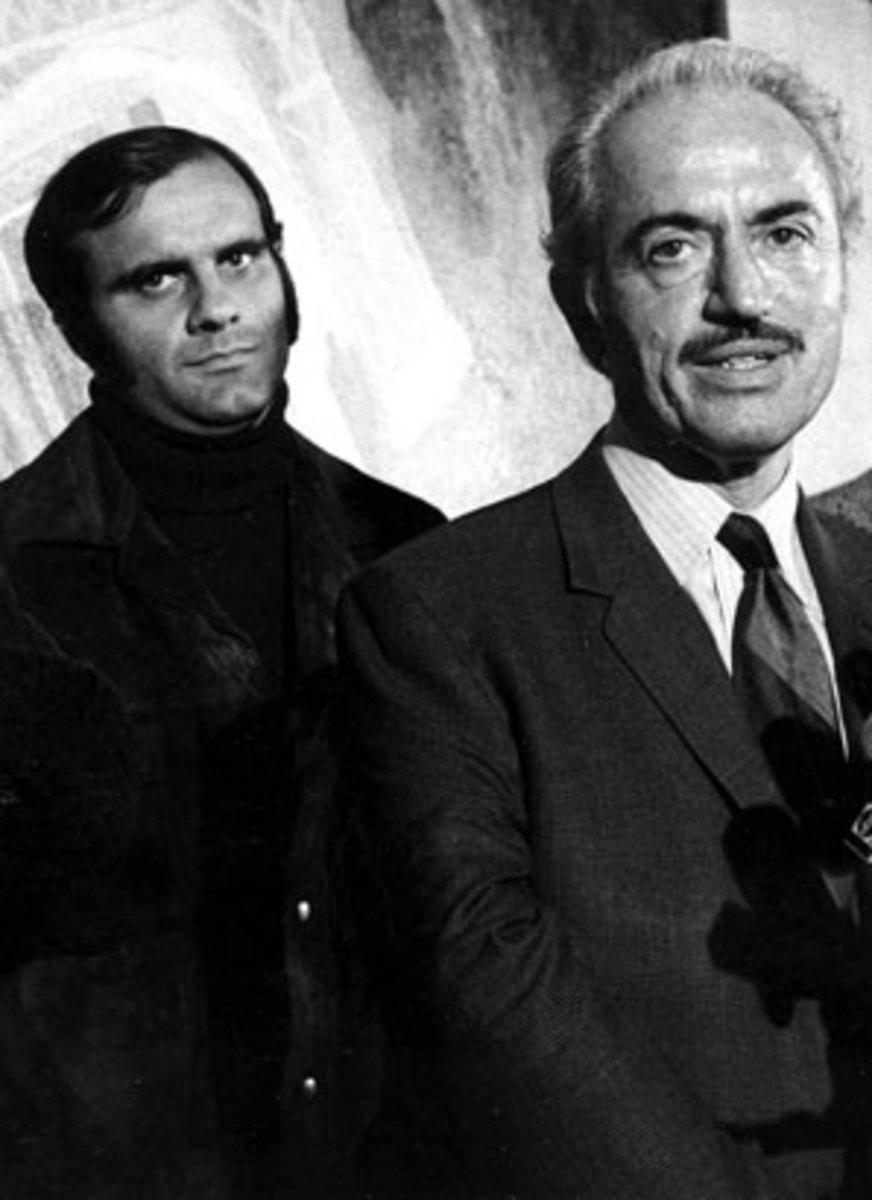

Marvin Miller changed players' union -- and baseball -- forever

The players were fixated on a single issue, griping about the state of the pension plan, but Miller was horrified by the broader picture. Relative to team revenues, wages were scandalously low -- over the previous 20 years, the minimum annual player salary had "grown," from $5,000 to $6,000. Working conditions were harsh, as management (i.e., club owners) asked labor to work without a day off for weeks on end and was unwilling to make investments on the order of padded outfield walls. Players were dismissive of the organization and the organization's coffers consisted of $5,400 in a checking account.

Above all, the "reserve clause," standard in every contract, stated that a team could renew a player's contract without the player's approval for the period of one year. The owners, however, interpreted this to mean that the clause could be renewed indefinitely each year, effectively tethering a player to a team until the club saw fit to trade or release him. When Miller examined the standard player contract he concluded that it was "one of the worst labor documents I've ever seen." Then, after the top two candidates rejected the offer, he took the job as executive director.

FORTUNE.COM: Q&A WITH MARVIN MILLER

By the time Miller, who died Tuesday at the age of 95, left office in 1983, he had singlehandedly changed the landscape. The MLBPA had become one of the most powerful labor unions not just in sports but in all of American industry, a model for how a unified bargaining unit with relentless leadership could gain concessions. Wages and salaries had improved dramatically. There were more jobs than ever. Most important, players had broken the bondage of the reserve clause and, through free agency, were able to receive maximum value in an open labor market.

"Marvin Miller took on the establishment and whipped them," crowed Reggie Jackson, one of the many players to benefit immensely from Miller's stewardship. Miller, though, had a more tempered view of his success: "It's not difficult to make strides," he once said, "in an industry a hundred years behind in labor relations."

Miller was born in the Bronx in 1917 and entered adulthood during the Depression. It was then, he says, that he learned the power of unity. From the start of his tenure in baseball, he cut a complex and sometimes contradictory figure. He was an unabashed liberal, who even dressed the part of the '60s counterculturalist, yet he advanced his arguments not with hot, radical rhetoric, but with cold, rational logic and economic principles. He was slight of stature and -- thanks largely to a right arm that had been mangled at birth -- not much of an athlete, yet he connected with his jock constituents. He enjoyed baseball and appreciated its place in the culture, but he would not let romance and nostalgia undermine his goals. While he could be combative and cutting and, at times, stubborn, he suppressed emotion during negotiations, seldom raising his voice, much less banging a fist on the table.

Apart from grasping the underlying economics, Miller understood one of the fundamental principles of labor relations: Win in the equivalent of a blowout and you create an aura of bad faith, the opposition girding for battle when the collective bargaining agreement comes up for renewal. (Labor and management "don't have to love each other," he once said, "but they have to live with each other.") Win, however, with the gradual, incremental victories, and that's you how make real progress.

Miller started with wages. In his first collective bargaining agreement he negotiated, the minimum player salary increased 40 percent to $10,000. Next, he set to work upgrading the players' pension plan -- which remains uncommonly generous to this day. In the 1970 basic agreement, Miller negotiated for the establishment of an impartial arbitrator to adjudicate grievances between the players and owners, a crucial gambit. (Prior to that, the final arbitrator had been the commissioner, the figure the owners had hand-picked to represent their interests.)

Once Miller had established the backing of his membership, he went after the reserve clause. It was St. Louis Cardinals outfielder Curt Flood who, both with Miller's gratitude and counsel, challenged the clause on anti-trust grounds, asserting that it was an unfair restraint of trade. While Flood eventually lost his case in front of the Supreme Court, he brought awareness to the issue.

Before the 1975 season, two pitchers, the Dodgers' Andy Messersmith and the Expos' Dave McNally, took over where Flood had left off, and, on Miller's advice, played without signing a contract (their teams, after all, still controlled their rights under the reserve clause) and then filed a grievance. Arbitrator Peter Seitz ruled in their favor, determining that the reserve clause was not renewable in perpetuity, that the one-year stipulation meant just that: one year. The owners fired Seitz the following day, but it was too late. The decision effectively ended the reserve clause and issued in the era of free agency.

It was the signature win of Miller's career, but he hardly stopped fighting, especially on issues of "worker" safety. He looked to improve everything from the scheduling of back-to-back doubleheaders to poorly-defined warning tracks. Under his guidance, the players went on strike for 50 days during the 1981 season -- "the association's finest hour" is how he characterized this unity in his memoirs -- and won still more concessions.

After leaving his post in 1983, Miller remained a consigliere of sorts at the MLBPA well into his '90s, venturing to the organization's midtown Manhattan office from his apartment on the Upper East Side. The players, once so impotent, had become too powerful in the eyes of some. It wasn't just that the players' salaries grew like Jack's beanstalk. Player conduct that, in other fields would be grounds for on-the-spot termination, was scarcely punished. (See: Steve Howe, a troubled pitcher who, thanks to provisions in the collective bargaining agreement, was suspended seven times for drug and alcohol violations, but never banned.) Critics cite the strength of the MLBPA in the "steroids era," noting the negotiated testing policy hardly deterred players from performance enhancing drugs. On these points, Miller was always unapologetic. The players had leverage and they were simply exercising it accordingly.

It was Red Smith, the venerable sportswriter, who declared Miller, "the second most influential man in the history of baseball." Babe Ruth was first. Bill James, the baseball historian and statistician asserts that Ruth, Jackie Robinson, Branch Rickey and Miller form the Mount Rushmore of baseball. In a 1994 poll of people who changed sports, Sports Illustrated once ranked Miller eighth, just ahead of Larry Bird and Magic Johnson.

Former players created the website www.thanksmarvin.com to pay homage to Miller. As one poster put it: "Those of us whose careers ended before free agency began in 1975 rarely made enough during the seasons to support ourselves and families without working in the off-seasons, never mind saving for the future. Thanks to this man, we now enjoy pensions, often greater than our salaries during our playing days."

If Miller aroused loyalty and gratitude from his constituents, he triggered proportionately strong contempt in other precincts. Some baseball purists saw him as an antichrist figure sullying a sacred pastime, turning players into mercenaries. The St. Louis Globe-Democrat once opined that Miller, "would do baseball a favor if he disappeared or got lost or found the nearest hole and jumped into it." For all the issues that divided club owners, they were in accord when it came to their opinions on Miller.

Given Miller's impact, his absence in the Hall of Fame is a glaring one. While the Baseball Writers Association of America votes for eligible players, the eligible "pioneers" are selected by a 12-member Veterans Committee, the majority of whom are current or former management members. So it is that marginal former commissioners on the order of Bowie Kuhn have been enshrined, yet Miller has been kept out.

"The failure to acknowledge Miller," James once told SI, "is a sort of symbolic holding on to the past, in the worst sense -- holding on to grudges, refusing to forget, refusing to move on."

Miller being Miller, he responded by calling the institution "a crock" and instructing his survivors to decline to accept any posthumous honor on his behalf.

Hall of Fame or not, his real legacy is the current state of the game -- not just players' rights and salaries, but the overall health of Major League Baseball. As he put it shortly before his death: "When I began . . . there were 20 major league franchises and they had a combined revenue of $50 million for the whole year. Last year, revenues exceeded $6 billion. That's the industry we've ruined with higher salaries."