Where are they Now: Catching up with Dan Gable and Larry Owings

Is he really going to cry?

Is the hardest S.O.B. in the state of Iowa really going to lose it right now? His voice cracks, his eyes flicker, and suddenly, he goes silent, grasping for words. His days now are spent talking -- talking on stages and in boardrooms across the country on the speaking circuit; talking to millionaires over dinners to raise money for a sport he’s trying to save; talking to strangers who still worship him like a god -- here in Iowa there are, at latest count, three bronze statues of him in the state. Yes, Dan Gable -- the most famous wrestler and most decorated coach in the history of the sport, the volcanic legend who was so combustible as a coach at Iowa that after losses he’d return home and punch holes into his young daughters’ bedroom doors -- has admitted that he has become more emotional these last few years, someone who finds himself now tearing up at the end of old movies. That softie had been nowhere to be found earlier in on this day as he navigated his black pickup through Iowa City while downing cans of Mountain Dew and breathlessly telling rollicking old wrestling stories that crackle like firecrackers.

But now it is late afternoon, and Gable is sitting at a desk in the cabin behind his house that is his place of refuge, and his throat has closed. Through the windows an orange sun is sinking just beyond the towering pines, and light glows his pale bald head. It is the subject of an old wrestling match from 44 years ago that has him go silent. Finally, Gable says in a quiet, raspy voice, “I know that the match affected my entire life. Just sitting here, talking about it … it hurts. I’m emotional about it. I’m emotional about it because there’s still a lot of meaning …”

Where Are They Now: Catching up with former Cavs guard Craig Ehlo

His voice trails off, and he lifts a hand to dry his eyes; something that’s been buried deep is suddenly resurfacing. Later, over beers at a local bar, when he’s asked how often he thinks about his loss in the 1970 NCAA wrestling national championships, he will say, without a beat, “Everyday.” His wife, Kathy, will turn to him and look as if she suddenly doesn’t know this man she’s been married to for 40 years. “No,” she says, disbelieving. “Really? Really?”

It was the greatest wrestling match of all-time. It was one of the greatest upsets in American sports: an unknown sophomore from the University of Washington slaying the god from Iowa State and one of the most astonishing streaks in sports history. It is the match that Dan Gable will say turned him into a great wrestler -- and yet he still has trouble bringing himself to talk about it.

But now he is about to try. First, though, he has a question about the man who beat him:

“Where is Larry Owings now?”

*****

Here is Larry Owings: sitting at his dining room table in his modest house in the Oregon countryside, 30 miles outside of Portland, on a May afternoon. He is turning on his iPad, hoping to find clips of the match that would change his life in unexpected and complicated ways. He has one VHS cassette of the broadcast but the tape is the only copy of the match he’s ever owned, so worn that he’s afraid that if he runs it in the VCR one more time the tape will be ruined forever. Lately he’s been calling around -- to the University of Washington, to the Wrestling Hall of Fame in Iowa named after the loser of the match, to ABC, which was there to broadcast the event -- to see if anyone can send him a DVD, but no one seems to have one. He Googles his name on the iPad. A Seattle Times article, “Whatever happened to… Larry Owings?” comes up, as well as the Wikipedia entry for Dan Gable. A few old black-and-white wrestling photos turn up in the image results, but mostly he finds himself staring at photos of strange faces. “Well, that’s not me,” he says, as he reads about the retirement of Larry Owings of Brownwood, Texas. The tributes to Dan Gable on the Internet are endless, but time, it seems, has forgotten the one man who beat him.

That’s the way Owings prefers it. While wrestling still consumes Gable’s life, it now occupies such a small corner of Owings’ -- a retired school administrator, his life revolves around his wife and his 15-year-old daughter Sami, his work with his church and maintaining his properties in the small town of Aurora, Ore. -- that even some of those closest to him are unaware of his wrestling past. Owings’ neighbor and close friend of two decades showed up to a tournament a few years ago and saw Owings in the stands wearing a shiny purple Washington jacket. “Larry, what are you doing here?” the neighbor said, then looked up and saw the banner that read LARRY OWINGS INVITATIONAL TOURNAMENT.

The way Owings sees it, there was his life before the match and his life after: before 1970 he was a nobody hungry to make a name for himself in the sport, though also an introvert completely unequipped for the attention that would come. He grew up the youngest of five Owings brothers, all of them wrestlers; Larry, overweight growing up, was always the least likely of the Owings brothers to go one to become a great in the sport. His four brothers, his classmates, even his coaches at Canby High when he started wrestling told him he was fat. When Larry was on his high school team, the coach used to joke that he was so slow that they’d have to drive pegs into the mat to see if he’s still moving. The teasing was merciless and nearly crushed him, but it also fueled him to drop the weight and spend extra hours in the gym, and by his senior year he was the best wrestler in the state, competing in national tournaments and Olympic trials. In 1968, in Ames, Iowa, he stepped onto the mat to face the Iowa State sophomore who was already considered the best wrestler in the country. Dan Gable won 13-4 in a match that would serve as the central motivation for Owings two years later.

“It was simple: I wanted to beat the guy who beat me,” says Owings. “The match changed my life,” he says, but then he suddenly adds, “but there was a time, a long time, when I wished it never happened.”

The words hang in the air. And then, having found a nine-minute YouTube clip titled Gable-Owings, Larry Owings taps the play button, and, with a strange mix of fascination and unease, he leans back in his chair.

*****

More than any other sport, wrestling is rooted in self-belief and desire: being big, strong, fast and talented can take you only so far; in the end, it is about endurance, stamina, conviction. Dan Gable will tell you that eighty percent of wrestling matches are decided before the first whistle blows. “One competitor already knows he’s going to win, and the other knows he’s going to lose before either steps onto the mat,” Gable likes to say. Once there is a seed of doubt planted in your mind, well, you’re probably doomed.

Gable remembers the moment the seed of doubt was planted entering the 1970 national championships at Northwestern University’s McGaw Hall. His career had been one of perfection -- he was 64-0 as a high schooler, a three-time state champion, and 117-0, with two national championships, entering the final collegiate match of his career -- and there was no reason for Gable to be anything other than supremely confident when he arrived with his teammates in Evanston. The night before the start of the tournament, a teammate asked if he’d seen the front page of the Chicago Tribune sports section. Later, in a quiet moment in his hotel room, Gable got his hands on the paper, and there, in big bold letters across the top of the paper was the headline I’M HERE TO BEAT DAN GABLE. “I’d never experienced that before,” says Gable. “There’s the verbal stuff, here and there. But in ink? I didn’t know you could do that. I was like, ‘Who would say that?’”

Where are they now: Catching up with Chamique Holdsclaw

The wrestler was an unknown coming off a 30-1 season at Washington, a reserved 19-year-old who didn’t appreciate anyone who suggested that any result on the mat was a foregone conclusion. “Was I annoyed?” says Owings. “Yes. Wrestling is just two people out there -- anyone can be beat, anything can happen.” Owings had dropped two weight classes to wrestle in Gable’s class at 142 pounds. During the weigh-in, an ABC reporter asked, “Larry, why, particularly with such a successful sophomore season, would you drop a weight class that will be impossible to win because of Gable’s presence?” Owings glared at the interviewer and said, “I’ll beat him.”

Gable’s obsession with preparation and routine was already legendary; the stories are almost outlandish -- but they are all true. Gable would go for five mile runs, then get inside a car and, with the windows rolled up all the way, turn the heater on full blast so he would return to his ideal wrestling weight at the end of the day. He would mow the lawn of his parents’ home in Waterloo, on a 100-degree Iowa summer day with double layers of jogging pants to burn calories. He would sprint from class to class on the campus at Ames, clutching course books and wearing weights tied to his ankles.

His intensity only grew when he became coach at Iowa in 1976; Gable was legendary for going to extreme limits to solve a problem. Gable loves telling the story of how he once had a freshman wrestler on his team who faded at the end of matches; to build up the wrestler’s mental toughness, Gable drove would drive the wrestler 10 miles out of town a several times a week after practices, and had the freshman run all the way back to campus as Gable followed him in his car. The wrestler would go on to win a national championship. Gable’s success was always due in large part of his ability to live in a bubble -- no distractions ever got in his way. When his teammates passed him in the tunnels they never expected a hello.

In Chicago, though, the bubble burst. The night before the finals he reluctantly attended a banquet honoring him as the sport’s Man of the Year. He was taking time out to do countless interviews, up until the very moment of his match: ABC’s Wide World of Sports requested that he tape a spot for them on the mat just minutes before the final. The line Gable had to recite was simple: “Hi, I’m Dan Gable. Come watch me next week as I finish my career 182-0.” Gable kept bungling the lines, and the take took half an hour; by the time he was finished, without having gone through his regular pregame warm-up, every seat in the area was already filled, and the match was about to start.

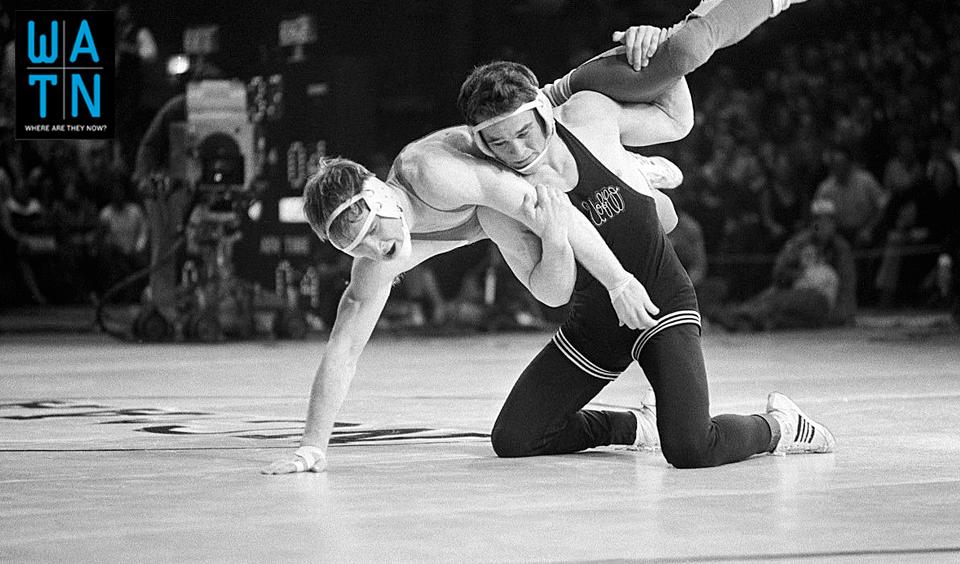

There had never been a day like March 28, 1970 in the world of wrestling, and there has never been one since. By the time the two wrestlers took center stage of the arena for the fourth match of the evening-- Gable in a sleeveless cardinal-and-gold jersey and separate trunks; Owings in a one-piece purple piece with “U of W” monogrammed on the chest -- it was so loud, with a standing room crowd of nearly 9,000 squeezed into McGaw Hall, that the wrestlers couldn’t hear the ref, Pascal Perri, unless they leaned in close. The atmosphere was electric, though what everyone had expected -- what ABC had come for -- was a coronation, not a competition.

Facing a wrestler legendary for his endurance, opponents of Gable would almost always go for broke from the opening whistle. Owings’ strategy in the match was his strategy in all his others: to wear out the other guy; he was, in short, going to out Gable Gable. “His gig was always that he was going to out condition people,” says Owings. “But that was my gig, too.” Over the first two periods the match went back and forth, and when the match stretched into the third period the energy of the hall seemed to change -- from frenzy to palpable anxiety -- as the crowd seemed to realize that Gable was in a fight. That Gable could lose.

It was the final moments of the third period that elevated the match into the realm of myth: 30 seconds remained, and Gable was ahead 10-9; if he could stall, if he could just bide his time, a third national title was his. “I had it,” says Gable. “And then I got greedy.” Gable had pinned an astonishing 70 percent of his opponents entering the final, and now he determined to pin Owings to close out his collegiate career. He attempted an arm-bar move, raising his arm over Owings’s shoulder to lock him up and take him down. Owings at that moment pulled off a move that he’d never done in a match: a leg sweep that caught Gable by surprise and dropped him down to the mat -- as Gable fell, he felt like he was going down in slow motion. Owings got four points for the move -- two for the takedown, two for exposing Gable’s shoulders to the mat. The move was so fast that Perri stopped the match and walked to the scorer’s table to ensure that the proper points were awarded. With 17 seconds left, Owings was ahead 13-11. The final seconds ticked down, and it was actually Owings, in the lead, who went for a final takedown. Gable was more exhausted than he’d ever been at the end of a match. “If we would have tied and there was an overtime, I don’t think I would have won,” he says.

Owings watches the video as Perri lifts his arm and Gable staggers away. “And that was it,” he says. The YouTube video cuts to black. “It was a good match, wasn’t it?” he says.

*****

The basement in the Gable home in Iowa City is full of trophies and trinkets and framed photos in glass cases; Dan Gable calls this part of the house the museum, and every museum must be a complete representation of history. In a corner of the room there’s a photo of Gable on the podium after the Owings match, a close black and white shot of his face with tears in his eyes. Looking at the photo now, Gable says, “I felt -- I feel -- like I let everyone down.” After Gable received his second place trophy, there was a loud ovation in the hall that stretched on for minutes, until one of Gable’s teammates approached him and said, “Gable, lift up your head. They’re waiting for you to lift your head.” Gable did -- and the cheering finally stopped.

Where Are They Now: Catching up with Cubs legend Ernie Banks

With none of his family members in attendance that day, Owings remembers staggering around, trying to process what just happened. “I was almost embarrassed to have won,” he says. Many who were there that day use the same words to describe the strange aftermath: it was like a bomb went off. Gable was in the locker room when he heard the water running in the shower. He walked over and saw his teammate Chuck Jean there. Jean was due to wrestle in the night’s final match, and the PA announcer called for the match wrestlers: Jean had three minutes to get to the mat. What are you doing? Gable asked Jean as he stood there under the water. “I’m not going out there,” Jean said. “I’ve never wrestled after you’ve lost a match, and I’m not going to do it now.” Says Gable, “You could say that this was my first coaching moment. I told him he had to get out there.” Jean made it out just in time; he won the match, and the national title.

Gable says that the loss was “like a death in the family.” “It just about killed my parents,” he says. “It was my mom’s worst fear.” Feeling stripped of his powers after his loss, Gable was finding out what it was like to be human. After returning to Ames the next day, the first thing he did was ask teammates to wrestle him. After beating up on them, he thought to himself, OK, I’m still good. In the days afterward he shut himself from the world. He holed himself up in his room, he didn’t talk to anyone, he didn’t even return his parents’ phone calls. One day his mother finally showed up at his door and when she saw Dan, she slapped him across the face, walked away, and made the one and a half hour drive back to Waterloo. “I could talk after that,” he says.

In fact, Gable would emerge from the Owings match stronger, more determined. “I say that I went undefeated for seven years, lost a match, and then I got good,” he says. “It would take me years to realize this, but I wouldn’t have become great wrestler and a great coach -- a legend in the sport -- without that match.” After he left Iowa State, Gable went on to win the 1971 Pan Am games and world championships, he took gold at the Munich Olympics in 1972 without allowing surrendering a single point; he went on to a 21-year coaching career at the University of Iowa, where he led the Hawkeyes to an unprecedented 15 national titles.

But the scars from 1970 would never go away, and not just for Gable. A few years ago, at a wrestling banquet, Les Anderson, a former assistant coach at Iowa State, pulled his former protégé aside, and said, “Gable, I just want to apologize for that last match. There were some things I could have done … We just thought you were invincible.”

Anderson was dying of cancer, and as Gable says, “It was like he was unloading a lifelong burden.”

*****

Where are They Now: Former UConn star Doron Sheffer

“‘I’d beaten the best in the world -- it was the pinnacle of my career, and would be, no matter what,” says Owings. “Where do you go from there?” Owings remained one of the top wrestlers in the country, but as disappointments mounted -- he finished second in the NCAA championships in 1971 and ’72 -- Owings began to feel like his national championship win was a curse.

He faced Gable on the mat one more time, at the 1972 Olympic trials in Anoka, Minn. Owings was wrestling best at 136.5 that year, but he struggled to keep his weight under 138. The night before the weigh in, he had a fight with his wife, who was seven months pregnant and didn’t want him to leave her and the baby behind and go to the Olympics. Owings thought to himself, I’m not going to the Olympics, Why am I cutting weight? “So I went up to 149,” he says, “and I told myself that he’d beat me, and everybody will leave me alone.” It was not a contest: Gable won 7-1. But neither wrestler found the peace that they sought: Gable walked away wondering, How could I have lost to this guy?. As for Owings, people did not leave him alone. “All people still wanted to talk about was that match,” he says. “Who wants to be known for just one thing?” He thinks about what would have happened if he would have lost his match: maybe he wouldn’t have entered a failed marriage in 1970 just months after the match (“Maybe she wouldn’t have married me if I wouldn’t have been a winner,” he says), maybe he would have pushed himself harder to become an Olympian.

Wrestling was already fading in his life when he met Diane, the woman who would become his second wife. They were on their first date when Owings asked if she was into sports. “Every sport except boxing and wrestling,” she said. Wrestling never came up until they went on a date later in their relationship and two strangers walked up to them and asked for Owings’ autograph. “Now why on earth would they want that?” Diane asked.

Every once in a while now Owings will still go to the mat. He will show up at a practice at a high school just a few miles from where he lives now, and he will stand in front of the teenagers and say, “If you can score on me, you can win the state title.” Some of the wrestlers will think he’s joking. He’s not. Owings looks like he’s one sweaty workout away from his wrestling weight at Washington. No high school kid can come close to scoring on Owings.

Owings shows up at local wrestling practices and events more, and when people ask him about the Gable match, he no longer tightens up. “There was a time I wished it never happened,” he says. “It was around the time I turned 50, and maybe that has something to do with it: I realized that I had a talent, and what’s the point of denying that I had that talent? When I started to embrace that, I started to become happier, I think.”

The young wrestlers have all heard of Dan Gable. Most have never heard of Larry Owings. That has never bothered Owings. What bothered him was how he was always introduced to the room, but now, it almost makes him proud, the words, “Larry Owings. National Champion. The man who beat Dan Gable.”

*****

A few years ago, the Republican Party recruited Gable to run for governor of Iowa. He was intrigued -- Dan and Kathy went to Washington to have a series of meetings at the White House. In his final meeting, he sat face to face with Karl Rove, who made the mistake of saying something to the effect of, You’ll do what we tell you to do. Gable said no thank you. Even now, no one tells Dan Gable what to do.

It’s been 17 years since he coached his last match, but his life still revolves around wrestling and fixing problems within in the sport, both small and big, from the new freshman at the university who needs a kick in the butt to the sport’s very survival -- last year, after the International Olympic Committee dropped wrestling as one of its core sports in February 2013, Gable made it a personal crusade to have it reinstated. Now he’s fighting for it to be reinstated beyond 2020. “The way I see it,” he says, “I’m the coach of the sport.”

Gable is 65 now, still works out every day on the elliptical and lifting his old high school weights, but lately he’s been feeling his body crumbling; he walks with a limp, the result of eight knee surgeries and four hip replacements. “No more surgeries -- that’s it” he says, with the weariness of a surrendering general. He has softened in his old age -- that’s what nine grandchildren will do to you -- and lately he has been more reflective; a stack of papers on the desk is the memoir he’s working on with a writer. He has come to peace with things he never thought he would. Earlier in the day, without any prodding, he brought up the murder of his sister Diane in 1964. Two years ago, Gable got the call that Diane’s killer had died in prison. Gable didn’t feel redemption or justice, only a heavy weight lifted: in an unexpected moment of clarity, he realized that all these years he’s somehow been partly blaming himself for her death. Now, it was like a burden was lifted.

There is, however, still the open wound from 1970. It’s harder and harder now for Gable to feel the fire that was in him for so long, but he becomes alive again, the old wrestler with the mean streak, when he talks about the Owings match. Maybe Larry Owings is the only thing that is keeping that part of him alive. He growls, “What I don’t understand, and what still pisses me, off is that how, I did not get up properly for the biggest match of the year. And that’s something that still pisses me off …

“Owings and I, we have an interesting relationship, that I just have never … let’s just say we’ve never become close,” he says. From inside his cabin Gable looks out onto the night fast approaching. Finally, he says, “There’s a barrier between us that I’m not sure needs to ever go away.”