League, players put season's gains at risk with looming lockout

It's hard to believe that such a miserable epilogue could follow so entertaining and popular a season as the NBA enjoyed up through a couple of weeks ago. But that was then and this is now: The league claims 22 teams are operating in red ink and that the current system no longer suffices.

The owners intend to create a new system that ensures profitability for each franchise. Their argument is that anyone who spends the going rate for an NBA franchise should not be asked in addition to lose money on an annual basis. The league cannot grow otherwise, they say.

The players respond that the owners can resolve their problems through revenue sharing (something they are negotiating among themselves even as they conduct separate talks with the players' union) as well as other fixes and minor cutbacks that altogether will enable small-market teams -- those that are run wisely -- to succeed financially. The players are not interested in absorbing major salary reductions in order to subsidize owners and front offices that routinely make bad decisions.

There are two major issues at play. Most important is the percentage of revenues that will go to the players, who currently receive 57 percent of NBA income (minus a few categories, such as the money that comes from arena naming rights, suites and so on). The players recoil at the owners' insistence that their share drop below 50 percent (based on the current formula). In reply, the union has offered to absorb an average of $100 million less per year over a five-year period, a proposal that commissioner David Stern termed "modest."

Nothing can be more important than arriving at a final decision on how much money the owners will keep and how much will be allocated to the players. Once they've reached that monumental agreement, then many of the other issues turn into negotiations on how the money should be delivered.

The other issue is the owners' desire for some form of a hard cap on player salaries, which would prevent the richest franchises from outspending the less rich. Stern has referred to the latest owners' offer as a "flex cap," in which the floor and ceiling for each team's budget would be subject to negotiation with the players. Union president Derek Fisher dismissed the plan as another derivation of a hard cap.

The players insist that a hard cap would reduce player movement and lead to the death of guaranteed contracts for most players. They foresee a hard cap leading to an environment in which the best players receive most of the money, while the majority of players wrestle over the remainder. Imagine the selfishness of teammates competing against each for touches and shots, they warn.

The outcome of the hard-cap negotiations will be significant, regardless of the eventual split in revenues. The hard-cap debate represents a philosophical difference between the two sides on how the NBA should be operated. For the first time in modern memory, it puts the players on the high-ground position of defending the health of the league.

The players have long been cast as seeking to bleed the owners in collective bargaining, to grab as much money as possible without regard for the long-term consequences to the NBA. Of course the players still want as much money as they can get, but by arguing now against a hard cap, the players are also fighting to maintain a system that succeeded in creating more championship-contending teams than we've seen in the modern era (dating to the 1979 arrival of Magic Johnson and Larry Bird). A hard-cap system would, according to the players, result in fewer deeply talented teams and, therefore, the NBA itself would be damaged.

The union also fears that player movement will be restricted by a hard cap, which means the league won't benefit from the kind of endlessly hyped speculation around LeBron James, Dwyane Wade and Chris Bosh that created large mainstream audiences throughout season. For the first time, the players can maintain a straight face when they claim to be fighting on behalf of fans.

But the owners' retort is not without validity either: that the current system is doomed to fail, and if the core problem of unprofitability is not resolved then everyone -- including players and fans -- will ultimately suffer.

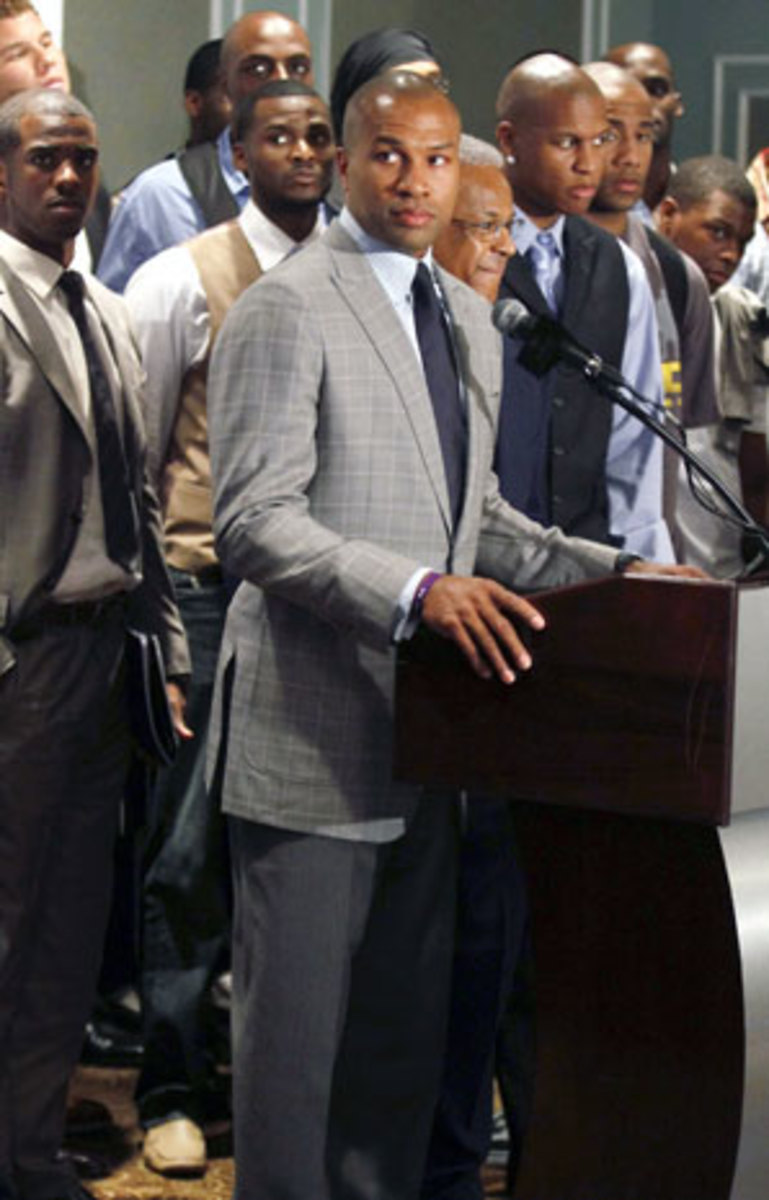

So far these negotiations have been relatively free of vitriol, but civility may be doomed as the deadline approaches. When dozens of players arrived last week at a negotiating session wearing identical T-shirts that read STAND, it was their attempt at a statement of unity -- that they would stand together even if they are locked out. No doubt the owners didn't appreciate it.

In recent weeks both sides have made compromises based on their original proposals, which from the beginning were viewed as extreme positions from which to bargain toward the middle. The reality is that the two sides are unlikely over the next several days to resolve their differing views of how the revenues should be divided.

The owners are now offering players a 10-year plan that would guarantee them $2 billion in salary and benefits annually; the players say it would amount to a salary cut in all but the last year of the plan.

Stern and deputy commissioner Adam Silver have insisted that the league wants desperately to avoid a lockout -- even an abbreviated exclusion will turn away fans and income while hurting the overall business in a variety of ways. Yet the threat of a lockout has always been the owners' biggest hammer.

If the players are compelled eventually to accept some form of large cutback in pay, they are unlikely to surrender to it this week -- five months before they receive their first paycheck for next season. As hard as both sides are working to negotiate an acceptable settlement before the collective bargaining agreement expires June 30, the pressure to complete a new deal won't heighten until training camps approach and both sides face the loss of some or all of the 82-game season. That's when the time for bluffing will expire, forcing the players and owners to understand and respect each other's positions, for better or for worse.

In the end, it comes down to the type of agreement that will be reached by the two sides. Will they find compromise on a new deal that minimizes the collateral damage? Or will they instead agree to damage their prospects for the future, squander the gains in popularity earned over the past year and convince fans to become disillusioned and discouraged?