Senseless NBA players, owners will look back on lockout with regret

Right now the owners are blaming the players, and the players are blaming the owners. If only the other side of the table would have shown common sense then an agreement would have been made long ago -- that's what each side is saying about its former partner.

But 20 years from now, when the emotions have boiled away and they can see this breakdown for what it is, the owners and players will also blame themselves. The wise people on each side of this argument will think about what they might have done differently, and they will realize the needless harm that was done.

There was no natural disaster at play here. Nothing beyond the control of the owners and players forced them to push this season to the edge of cancellation. They did this together.

They will continue to blame and complain about each other. But any person of reason, watching from afar, is going to recognize blame on both sides of the table. You may feel more anger for the owners or for the players, but if you are a fan of basketball then the bottom line is that you are angry with everybody who had anything to do with the fact that there is $4 billion in revenue on the table and they can't even talk any longer about how to share it.

For the NBA owners and players to shut down their league during the worst economic times in more than 60 years has got to be the dumbest thing they could imagine doing. At a time when so many businesses are fighting for every last dollar, the NBA players and owners are giving back money to their season-ticket holders -- their die-hard fans -- and saying we don't want it. Put that money back in your pockets for now, and when we decide to start playing again, think about whether we are worthy of your investment.

The priorities and sensibilities of the owners and players exemplify an arrogance that now threatens the future of their business. But the players and owners don't see it that way. They are too focused on viewing their relationship as a divorce rather than a marriage.

Someday the owners and players are going to view this argument the way millions of people around the world view it today. At that time in the distant future, when it will be far too late, everyone involved is going to feel regret for his role in a mess that -- given the economic environment and the pessimistic mood of the country -- threatens to become worse than the Tim Donaghy scandal, the 2004 brawl in Detroit and the 1998-99 lockout combined. This breakdown was not set off by the union's legal maneuverings on Monday, and it didn't happen with commissioner David Stern's recent ultimatum. It goes beyond the lockout of July 1 or the launching of negotiations more than two years ago.

It goes back to when the losses were starting to pile up among the smaller-market franchises, as they realized they were being outspent by the deeper-pocketed teams. If Jerry Buss, Jim Dolan and other big-market owners had been willing to share their revenues earlier and more comprehensively for the greater health of the league, could the division among owners have been headed off?

Or look at it from the other side of the owners' room. If so many of these small-market owners had operated their teams more wisely and efficiently, might the bigger-market teams have been more willing to share money with them on good faith that they were investing in the health of the league?

And then could the owners together have not inched forward on a few points of contention here and there in order to ensure agreement with the players?

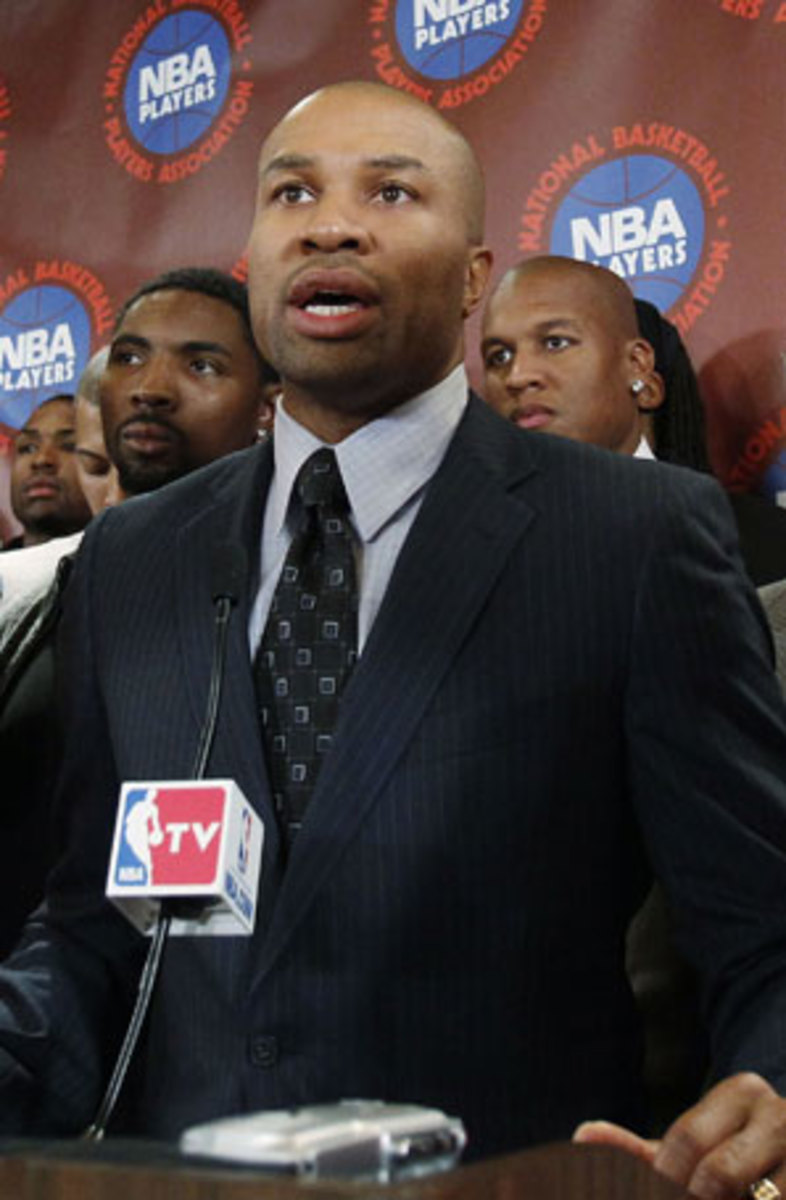

There will come the day when everyone is going to hold himself accountable. How much did union executive director Billy Hunter learn from the lockout of 1998-99? Not enough, it appears, for he failed to organize a system to deal with the crisis in which he and the players now find themselves. Why wasn't every player in the league provided a copy of the final NBA proposal? Why were there so many breakdowns in communication between players and their union representatives?

This will be a subject of enormous dissension and regret moving forward, as scores of players will insist they would have voted in favor of this proposal if presented with the opportunity. As the months pass by and the reality settles in, there will be complaints of how the chain of command broke down and the membership was failed. This is a small union of less than 500 members with equal voting rights, and yet many of them believe they had no say in this decision to file a lawsuit rather than begin the season Dec. 15. The union leadership spent the last two years warning players to save their money, yet the same leadership didn't prepare itself to learn from the mistakes in communication of 13 years ago.

How did Stern lose his ability to reason with Hunter and the players? How is it that a leader who has empowered African-American culture more than any other commissioner (remember the Allen Iverson era when the NBA was accused of being too hip-hop?) is now facing veiled charges of racism and plantation governance?

Over the last decade Stern has seen his relationships with the players suffer, much as his leadership of the owners has suffered. The players appear to view him as some kind of dictator who enforced a dress code and a respect-for-the-game rule, while giving him little credit for raising their average salary to $5 million; he surely played a role in transforming the negative image of NBA players in the 1970s to help them become popular around the world. Yet something went wrong somewhere along the way, and Stern went from being the partner of players (as he was during the era of Magic Johnson and Larry Bird) to being viewed as their dictator. Perhaps this was a natural progression for someone who has been in charge for so long. Someday, in his heart of hearts, he will wonder where it went wrong, and the part he played in this breakdown of negotiations.

The same can be said for the group of powerful agents who encouraged the legal action that was taken by the players Monday. They surely will regret their failure to push for decertification earlier, when there was a stronger chance to save the season. As time goes by and their clients suffer, will these agents be viewed as contributors to the players' suffering? I believe they acted in good faith, as a result of frustration for their clients and themselves. But there may be unexpected consequences for their agenda, and especially for their sense of timing. Someday there is going to be a deal, and it will be very easy for the players to compare the terms of that agreement against the collectively bargained agreement they could have had Monday, in addition to a 72-game season.

Someday, too, the players will regret their moves, step by step along the way. As of this day they view the league's final proposal as an ultimatum. As the years go by, however, they may come to realize that the proposal of a 50-50 split and other concessions was the best offer that Stern could negotiate for them, and that while trying to herd his divided owners he was essentially negotiating on behalf of the players. This statement is going to anger players and agents, but I believe it to be true: I believe Stern wanted sincerely to save the season, and that he marshaled his political capital in forcing owners to put forth a proposal that the players may be able to accept. Everyone knows that many of those owners were not happy with the deal Stern offered.

Imagine the regret so many players will experience 20 years from now. And for what? They had surrendered a lot of money in these negotiations so far, and in the end they refused to accept every last dictate of owners, which is understandable in light of the players' polarization from the owners. In the bigger picture, however, the players' stance does not reconcile with the realities of the time in which they live.

Recently an essay by Etan Thomas posted on ESPN.com chose to compare the plights of the players union with the stand taken by the so-called 99 percent who have formed the "Occupy" movement on Wall Street and other locations around the world. I have enormous respect for Thomas, a sensitive poet who is serving his union's executive board for no pay because he believes in the principle. This is why I could not believe how out of touch he was to view the mission of his union as having anything at all in common with the movement to Occupy Wall Street. How in the imagination of any reasonable person could a player in the highest-paid league in the history of mankind begin to compare the terms of this $4 billion negotiation against the people who are unable to feed their families, who have lost their homes to foreclosure and who believe they have been neglected by employers and government?

If someone as smart and sensitive as Etan Thomas cannot recognize the great fortune that has placed him among the elite 1 percent, and how very little the rest of the world will sympathize with his cause, then what hope is there for any common sense to prevail amid this senselessness? He and the players talk about principle, but what will they be saying about the high price of that principle 20 years from now?

Here is the fundamental problem, and I believe 99 percent of you will agree with me: The owners and players share too much in common. People on each side of the table believe absolutely that they are in the right, that they won't be dictated to, and that they would rather see no season in 2011-12 than to surrender to their partners-turned-enemies.

The result is that they are all doomed to regret their role in what has happened. Because someday they're going to think about why they got into this business. The owners bought into the league because they love sports, and the players have always played because they love to play. That love is what brought them together, and now look at the harm they're doing to the thing they love most.