NFL watching, but not expecting to strip Haslam of Browns ownership

In the relatively short but tortured history of the re-incarnated Cleveland Browns, every dark cloud appearing on the horizon has generally presaged a darker and more ominous one, leading the team's fans and even the organization itself to develop an almost instinctive, reflexive flinch when it comes to the potential for bad news and the consequences of poor decisions.

From the tone-setting selection of quarterback Tim Couch, to the hiring of a string of out-matched head coaches and front office executives, to the glaring shortcomings of ownership in the team's Lerner era, the Browns have become as familiar and intimately acquainted with the worst-case scenario as any team in the NFL. After all, there has been little else to rely on in the mostly miserable past 14 years in Cleveland.

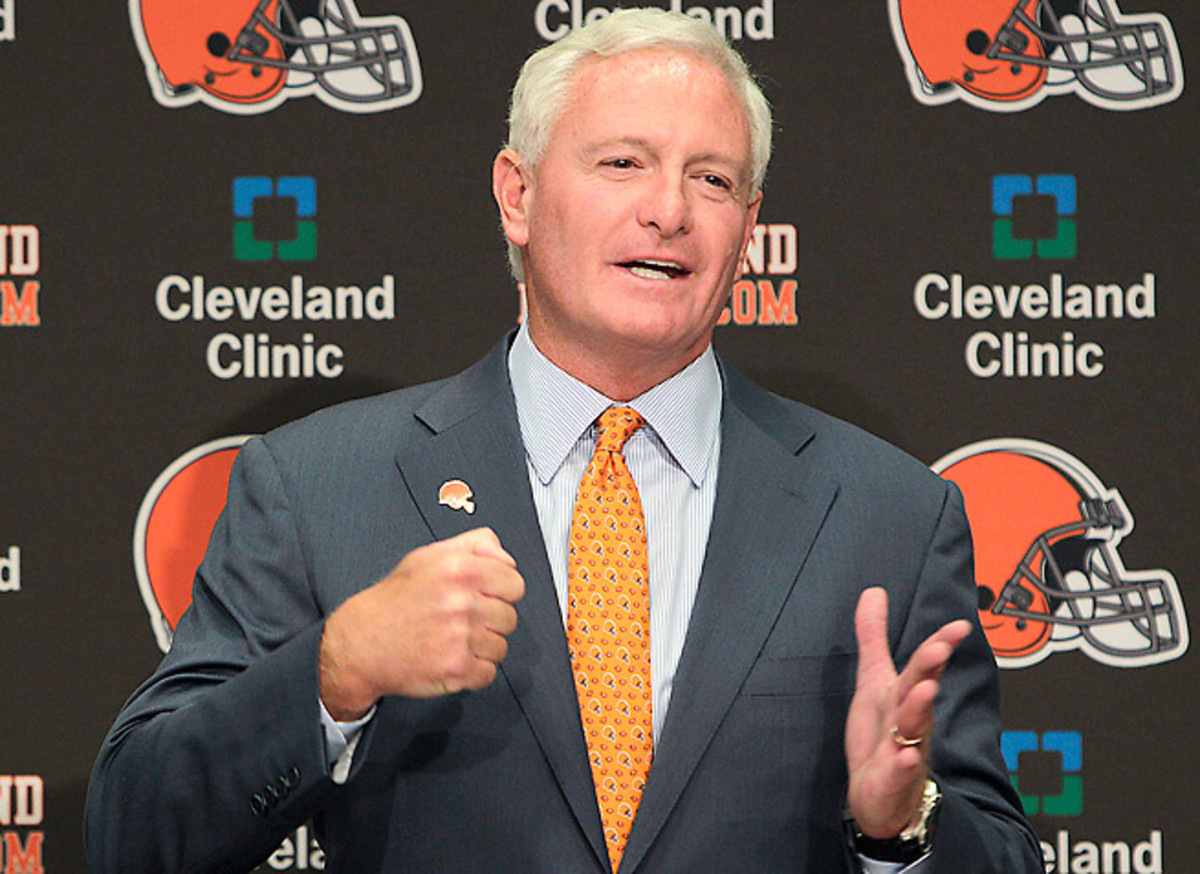

Which is why when the alarming news broke last month that first-year Browns owner Jimmy Haslam's family business was under federal investigation, many were quick to view it as yet another staggering blow being dealt to a franchise that has seemed trapped in a perpetual cycle of failure and attempted turnarounds. Cleveland, where gloom and doom have taken up permanent residence, and hope springs ephemeral.

But in this case, even if it is a sobering federal case that included the FBI raiding the Knoxville-based corporate offices of the Haslam family truck-stop chain, the here-we-go-again lament might be a bit premature for the Browns and their long-suffering fan base. We're always one news cycle away from the narrative changing in today's NFL, but for now there's no real sense the sky is falling in Cleveland and that Haslam's legal troubles will seriously imperil his ownership and completely snuff out the optimism his presence brought to town, almost before it has a chance to truly take root.

When the NFL team owners convene at a Boston airport hotel next Tuesday for their one-day spring meeting, the matter of Haslam's Pilot Flying J company being investigated by the government for a scheme involving diesel fuel rebate fraud will be the elephant in the room. In a league that covets stability and cringes at the effect that bad publicity can have on its reputation and bottom line, Haslam will naturally find himself in an unwanted spotlight among his 31 league partners.

NFL sources say they don't know whether he plans on addressing the controversy in front of the entire group or in a series of individual meetings with his peers, but acknowledge that Haslam likely has some "internal communications planned'' for the meeting and that he had expressed a "regretful and apologetic'' stance in his talks with league commissioner Roger Goodell, for creating a problem for the league in his first year of team ownership.

Haslam's legal issues have nothing to do with the Browns per se, but everything to do with his ownership of the team, and thus his fellow owners will be eager to hear from him and where he perceives the case is headed. In talking to league and team sources this week, Haslam is described as remaining resolute in his desire to make restitution to any trucking companies that the scheme affected, even while maintaining that neither he or his high-profile family -- Haslam's younger brother, Bill, is the governor of Tennessee -- were part of or aware of any illegalities being conducted in a $20 billion-plus privately held company that numbers more than 20,000 employees and includes more than 500 truck-stop locations in the U.S. and Canada.

That, of course, is not the same picture painted by a Pilot Flying J employee in the FBI affidavit that was unsealed last month, who told investigators that Haslam, the company's CEO, was present at sales meetings where the company's fraudulent rebate scheme, executed over many years, was discussed.

But if there's a temperature reading to be taken internally within the league regarding the status of Haslam and his ability to own and lead the Browns, it's a long way from the doomsday scenario that some early media reports portrayed, characterizing some team owners as "absolutely terrified'' and "scared to death'' at the potential damage the investigation could do to the Browns organization.

While no one within the league office is taking the possibility of a felony conviction against Haslam's company lightly, sources quickly point out that Haslam has not yet been personally charged with any wrongdoing, and say the Browns owner and former minority owner of the Steelers remains a known quantity within the league who has both the trust of Goodell and his fellow team owners.

To be sure, the Browns and the NFL didn't need this kind of development drowning out the positive vibes generated by Haslam's purchase of the team in 2012. But the league is also not ready to lump Haslam's legal plight in with that of a former NFL owner with ties to Ohio: ex-49ers">49ers owner Eddie DeBartolo Jr., the Youngstown native who pled guilty to a federal felony charge of bribing former Louisiana governor, Edwin Edwards in 1998, receiving two years of probation, a $1 million fine and a year's suspension from then-NFL commissioner Paul Tagliabue.

The key distinction in how the NFL views the two cases at this point is this, league sources say: DeBartolo was involved in an individual criminal matter, as opposed to being found responsible for a corporate act of illegality, as Haslam would seem to face. DeBartolo admitted to his role in the bribery, and even voluntarily recused himself from control of the 49ers in December 1997, just before being indicted by a federal grand jury. Haslam has repeatedly proclaimed his innocence and maintains the rebate fraud was the act of a small group of rogue employees who bent the rules for their own financial gain. He has promised to make restitution with interest to companies who have been cheated, and to put in place a chief compliance officer to restructure and oversee the company's rebate program.

But playing out the worst-case scenario that has been the Browns' fate in many other matters since their re-emergence in 1999, what would Haslam's potential fate be if he or his company were indeed convicted of a felony relating to the fuel rebate fraud? While DeBartolo's conviction of 15 years ago might not be the perfectly framed precedent, at least widely drawn the situation would seem to leave Goodell with little choice but to suspend Haslam for a year. Discipline of some sort would almost certainly be forthcoming from the league, NFL sources says.

Unless another part of the DeBartolo example short-circuited the need for such a penalty. DeBartolo stepped aside from leadership of his team once an indictment was on the way, ceding control to his sister, Denise DeBartolo York. He eventually lost control of the team to York in 2000 when the family divided its business assets, but DeBartolo had the opportunity to retain his ownership in the 49ers and opted for the family real estate company.

Haslam, league sources say, could be in the position to execute a similar family-related transfer of control if it became necessary due a felony conviction, and could choose to take that step proactively before the league has to issue any disciplinary ruling. The NFL has said it would not ask Haslem to step aside while the investigation continues, but Haslem is believed to have three or four family members with a stake in the team's ownership, and could deal with a suspension or a recusal by temporarily transferring the team to either one of his two grown daughters, or perhaps even his 82-year-old father, Jim Haslam, the founder and patriarch of the family business and a still very-active former University of Tennessee football player and member of the school's 1951 national championship team.

Providing no other Haslams are involved in the fraud case, the keep-it-in-the-family approach represents the most obvious and convenient way for Haslam to deal with any potential penalties from an NFL ownership standpoint. He would still be able to protect his ownership interest in the Browns, and give the league's other 31 owners the certainty that his family had the financial wherewithal to operate the team while he was serving some form of disciplinary action. And by not waiting for Goodell to act first, Haslam's road back to full acceptance among league ownership would likely be a quicker and smoother journey.

But for now, at least according to league and team sources, the idea of Haslam having to change his long-term status in team ownership in reaction to the fraud case seems unlikely. There's a long way to go in the Haslam case, but for once, the Browns might just steer clear of the worst-case scenario.