The Incredible Feats of Young Andy Reid

Gary Gramling and Susan Szeliga contributed research for this story.

The Eagles and Colts were in the fourth quarter and heading toward a tight finish, when, during a break in the action, CBS cut away to an unexpected gem. The clip re-appears every few years now, it seems, whenever a producer wants to get a laugh.

It’s a video of the Punt, Pass, and Kick competition between Los Angeles area youths that took place on December 13, 1971, during halftime of a Rams-Redskins game that was broadcast on Monday Night Football.

On the field at the L.A. Coliseum, there’s a line of six boys dressed in Rams uniforms, taking their turn throwing a ball as far as they can downfield. Only, the kid at the front of the line is about twice the size of everyone else. He looks like an adult who’s wandered onto the field. It’s Andy Reid, all of 13 years old.

“A little bit of a size advantage,” Jim Nantz said, chuckling, as the clip ended.

To be fair, the kids lined up behind Reid were in younger age groups. But over the years, Reid has grown accustomed to remarks like that; they were common throughout his childhood. He grew up in the Los Feliz neighborhood of Los Angeles, just south of Griffith Park and east of Hollywood. Due to its proximity to the movie studios, Los Feliz was home to many of the film industry’s working class. Reid’s father, Walter, was a scenic artist who made backgrounds and props for film, TV, and stage production. The family lived on Holly Knoll Drive, just down the street from John Marshall High School, which is where some of the scenes of the movie Grease were shot. Young Andy spent a lot of time down at the high school hanging around the football field, working as the team’s water boy. One day Reid was hanging around when Mike Haynes, the future Hall of Fame cornerback who attended Marshall High at the time, asked him: Why aren’t you suited up?

Because I’m 12 years old, Reid replied.

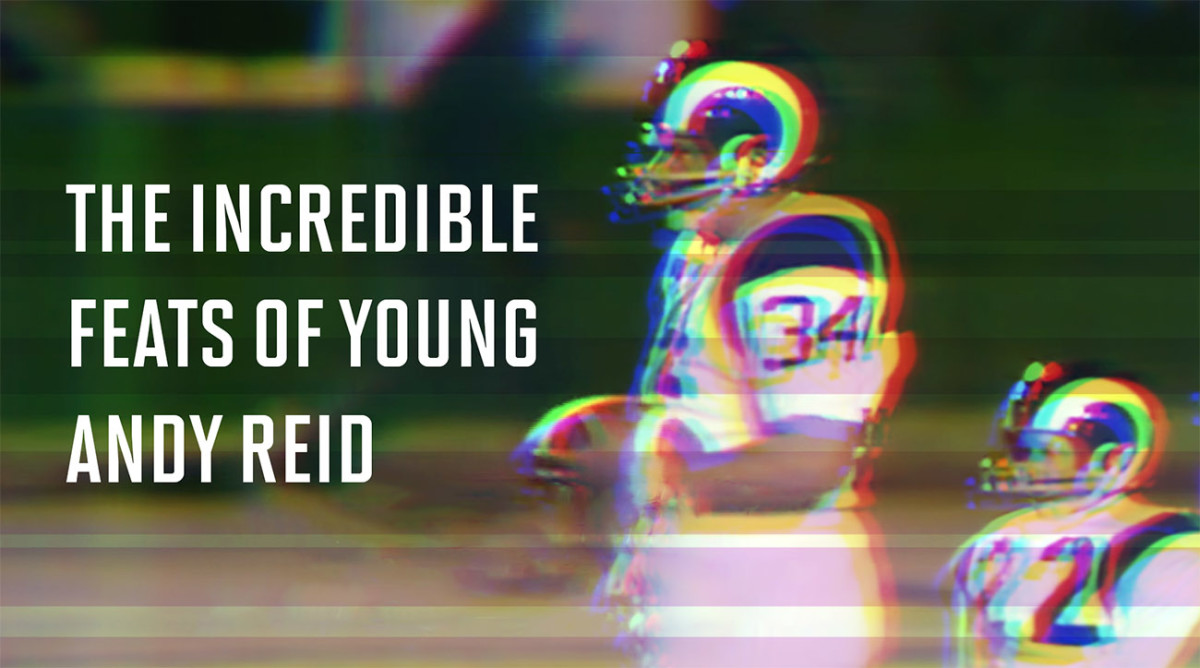

Reid's Hollywood Little League team photo, circa 1970. The 12-year-old Reid is in the middle of the back row, in the adult-sized jersey.

Courtesy Tony Stewart

There was a group of kids in the Los Feliz area who were Reid’s age, with whom he would always play sports. There was Bobby Volkel, the quarterback who lived across the street. There was Ted Pallas, who lived around the corner, and his buddy Tony Stewart, who were both pretty good baseball players. Then there was Andy Reid, the manchild.

They’d go down to Marshall High and hop the fence, or have someone jimmy their way in if they had to, and then play all day long. Baseball, basketball, football—whatever was in season. “It was the good old days where you’d get on your bike, you’d play all day, and you’d go home when the street lights came on,” Stewart says. Afterward, they’d sometimes go to Tommy’s, the classic L.A. burger joint, and compete over who could eat the most double chili cheeseburgers. The other boys could eat two, maybe three. Reid could eat as many as five of those things in one sitting.

“His waist was probably twice as big as mine, and he was probably eight inches to a foot taller than everybody,” Pallas says. Ken Gerard, one of Reid’s physical education teachers at Thomas Starr King Junior High School, estimates that, at 13 years old, Reid stood about 6' 2", and weighed 220 pounds. Reid’s friends confirm, he was right around that size.

VRENTAS:Andy Reid Is Creating Football’s Future, and Patrick Mahomes Is Living It

It gave Reid a distinct advantage in sports. When they played Little League baseball, Reid was so big he wore an adult-sized uniform. He was a catcher, and Stewart remembers one game when he had the misfortune of rounding third just as Reid caught the relay throw at home. “I remember colliding into Andy with all of my might, and then bouncing off him like a cartoon,” Stewart says. “I was lying on the ground and Andy picked me up like, ‘Hey, you O.K. buddy?’ I gave it all I had, but it was like hitting a wall with my 80-pound frame.”

Some of the home runs Reid hit back then are still talked about in reverent tones among his friends. At the Lemon Grove Rec Center, Reid is said to have once hit a ball over the 20-foot wall beyond centerfield and onto The Hollywood Freeway. At Franklin Avenue Elementary, there was a story that Reid once smacked a ball so far that it bounced into the school, where some women from the PTA were making hot dogs, and landed in the hot dog pot.

When the boys played basketball, Reid was always one of the first ones picked. He could’ve dominated every game in the post, if he wanted to. But he also had a dash of shimmy shake in his game. He could hold the ball over your head, cause you to turn around, and then pull it back and shoot it. “He had a couple of moves where it was like, Where did that come from, Andy?” says Volkel. “He had a pretty good shot, too. He had soft touch for a big guy.”

BREER:Why the Andy Reid Coaching Tree Has Been So Successful

But Reid’s favorite sport was football. When the boys were growing up, the Volkels had season tickets for USC football, and they’d bring Reid to a few games every year. Mr. Volkel was a USC booster and a diehard fan; he liked getting to the games early, so the boys spent a lot of time wandering around the L.A. Coliseum. They’d go to the end zone, wait behind the uprights, and try catching footballs as the kickers warmed up, as if they were trying to catch foul balls at a baseball game. They’d go down near the tunnel where the players came and went and try to get autographs. Then they’d watch the players going through their pregame calisthenics. Those USC teams were pretty good, too. The Trojans won the national championship in 1967, 1972, and 1974 (ages 9, 14 and 16 for Reid).

After the game, once they got back to Los Feliz, they’d often play their own game of football—usually touch, but not always. If Reid wasn’t on your team, it was almost unfair. A few times, Volkel was so frustrated that he tried attacking him. “You couldn’t take Andy on. Like, no way would I try to fight him one-on-one in those days,” Volkel says. “But if we were mad at him, we would kind of surround him. Ted would be on one side, me on the other, and we might try to take him together. [The fights] never really escalated and they never lasted very long. I don’t think we ever won.”

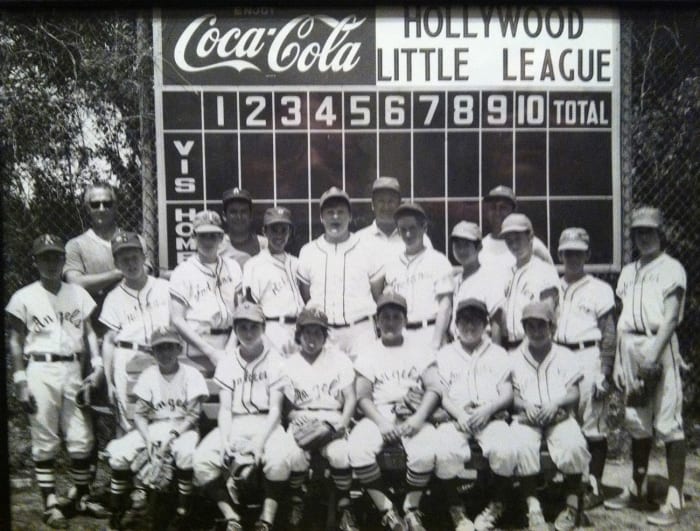

Not that Reid was one to throw his weight around. In fact, in junior high, he was a member of a group called B.M.O.C.—the Big Men on Campus. Organized by one of the Thomas Starr King P.E. teachers, B.M.O.C. was comprised of bigger kids, most of them athletes, whose job was to essentially patrol the school, break up fights, and keep the peace. The school apparently had an issue with gangs at the time. “When you’re that size, people can target you,” says Lee Bruno, another one of Reid’s friends from Los Feliz. “But [Andy] always found a way to avoid conflict.”

Reid (back row, second from left in black jacket) with the Thomas Starr King Junior High Big Men on Campus, who helped keep the peace around the school.

Courtesy Tony Stewart

Reid kept himself busy playing sports. Pallas and Reid signed up to participate in the local Punt, Pass, and Kick competition three or four years in a row. Back then, it was a nationwide competition sponsored by the NFL and the Ford Motor Company, for kids between the ages of 8 and 13. The basic idea was: One punt, one throw, one kick. Then you took the sum of those three distances to determine the winner. But accuracy counted. If your attempt was off the mark by some number of feet, that distance was subtracted from your score. “It was just something to do, basically,” Pallas says. “We were all competitive. It was like, why not?”

Pallas remembers he and Reid would spend a month or two practicing at Marshall High leading up to the competition. Gerard, Reid’s junior high PE teacher, remembers Reid asking him to stay after school to help him practice. They’d take a bunch of footballs and spend an hour out on the grass field adjacent to the school, just the two of them.

Half the time, Reid would kick the ball over the fence onto the school grounds—he was starting to become a pretty good kicker. When Reid was in high school, he would play on the offensive and defensive lines, but also serve as his team’s placekicker. He famously won three games on last-minute kicks. Once, one of his kicks broke a church window across the street. He approached the ball straight on and toe-poked it with his big right foot, which was the style back then. “[In high school] he had one of these George Blanda kind of shoes, like a placekicking shoe,” Volkel recalls. “It had this blunt nose on it, kind of like a flat nose. This was before they did the soccer style. You’d just go straight at it and … boom! He could really boom it.” Reid’s range was said to be 40 yards.

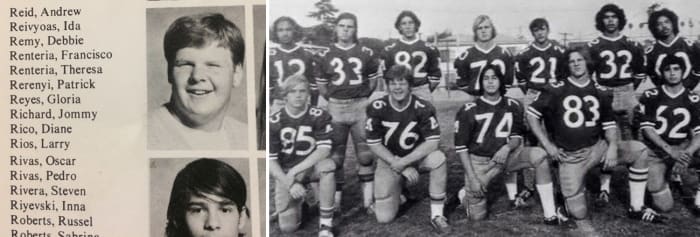

Andrew Reid, in ninth grade (left), and with the 1975-76 Marshall high football team (right, No. 76) a few years later.

Courtesy Tony Stewart

The kicking and punting portions were where Reid really separated himself in Punt, Pass, and Kick. After all, everyone practiced their throwing, but what 13-year-old took the time to practice kicking? In 1971, behind the strength of his right foot, Reid won his region and then kept advancing until he reached the L.A. Coliseum, where he’d compete against kids from all over Southern California.

At that stage, there were a dozen boys remaining, two from each age group. One boy from each age group would advance. They would do the kicking and punting portions of the competition beforehand, and then they would throw their pass at halftime of the Rams-Redskins Monday Night Football game at the Coliseum, in front of a national TV audience.

For this round of the competition, the kids dressed in full Rams gear. But when Reid arrived, organizers had to scramble to find him a jersey—none of the youth sizes came close to fitting. They ended up going into the Rams locker room and grabbing a jersey from Les Josephson, the Rams’ starting running back who was listed at 6' 1", 207 pounds.

Warming up on the field, Reid later told his friend Lee Bruno, he played catch with Sonny Jurgensen, Washington’s starting quarterback. Both Jurgensen and Reid had red hair, which caused one teammate to call out: Hey, Sonny, is that your little brother? In reality, Reid dwarfed the Hall of Famer. Jurgensen was listed at 5' 11", 202 pounds.

Once halftime arrived, the Punt, Pass, and Kick competitors trotted out onto the field, all of these small children, dressed in their little Rams jerseys, and there was Reid, in Josephson’s jersey, towering over them.

One of the youngsters there that year was 8-year old Bobby Cunningham, from Long Beach. He’s the pipsqueak standing directly behind Reid during the competition. Cunningham has seen the video of the two of them, but he has no recollection of Reid from that day. “He was a big guy back then,” Cunningham says. “I was a little guy, even for an eight-year-old, so the discrepancy was striking.”

Now, Cunningham works in construction in Florida. Recently, he thought about writing Reid a letter, asking if he could come meet him when the Chiefs played in L.A. “Obviously I never did it,” he says. “It was just a fun thought.”

Next in line was Steve Sukut, a nine-year old competitor from Laguna Niguel. He remembers meeting the Rams before the game and having them sign his game program. There was Roman Gabriel, Jack Snow, Merlin Olsen—he’ll never forget meeting Olsen, his idol. As Sukut gawked at his size, Olsen lifted the boy off the ground.

Sukut still lives in California; he works in real estate now. He doesn’t remember Reid from the competition, either. “Back then, you wouldn’t have noticed, because he wasn’t famous then,” Sukut says. “I’m sure we must’ve noticed.”

Up in the stands that day, Reid had a mini cheering section. Gerard had brought Bobby Volkel and some of Reid’s other friends to the game, and they were going crazy. Andy’s on the field! At the Coliseum! “It was so surreal,” Volkel says. “It was like, Whoa, there he is!” Granted, Reid had been easy to pick out.

Back in Los Feliz, the game had been blacked out, but Pallas and Stewart weren’t going to miss their buddy’s big moment. Stewart’s father made a phone call, and the two boys watched the game from the ABC studio over on Prospect Ave. As Reid came up to take his turn, his name flashed across TV screens across the country: “Andrew Ried, Los Angeles, Calif.” Someone had misspelled his last name, but the boys didn’t seem to mind. “He was like a hero to us,” Pallas says. “We were just thinking, My God, one of our best buddies is on TV!”

All these years later, no one can seem to remember whether Reid even won. Sports Illustrated conducted an extensive search of Los Angeles area newspapers from that time, and found no mention of that specific event, or of Reid winning.

“I’m pretty sure he won, because he got a really nice trophy,” Volkel says, but admits he could be mistaken. Last week, Stewart texted Reid, asking if he won, and Reid didn’t remember. The Chiefs declined to make Reid available for this story; he is busy preparing for Sunday’s AFC title game, during which he will, once again, be on TV.

Apparently, the only evidence that remains from that Punt, Pass, and Kick competition is that brief video clip that TV producers like to pull up from time to time. Well, that and the memories of the people who witnessed for themselves the athletic feats of young Andy Reid.

Not so long ago, when Reid was coaching the Eagles, Ted Pallas and Tony Stewart went to Philadelphia for a game. Afterward, Reid invited them back to his house to have dinner, catch up and reminisce. He gave them a tour of his den, which was decorated with years of memorabilia earned during a long and distinguished NFL coaching career. Among it, Stewart noticed a nondescript paper certificate: Thomas Starr King Junior High, Athlete of the Year.

• Question or comment? Email us at talkback@themmqb.com.