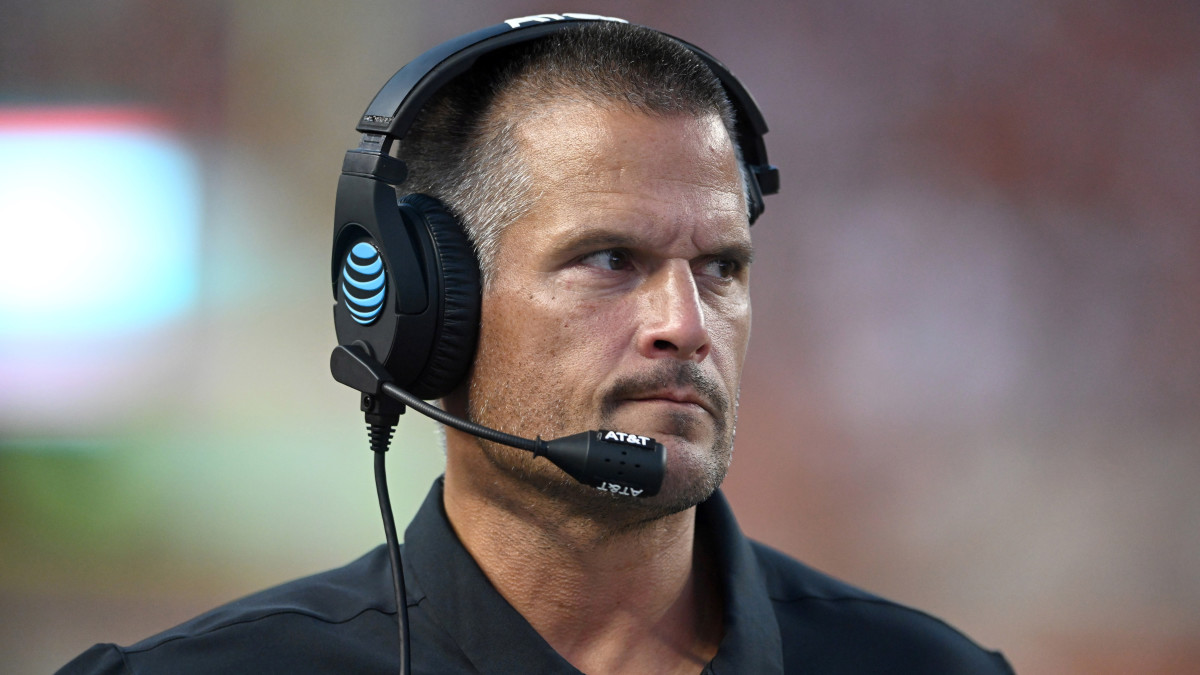

Texas DC Todd Orlando and the Unenviable Task of Slowing Oklahoma's Jalen Hurts

AUSTIN, Texas — If he would have passed a test, Todd Orlando might not be here right now standing in the Texas players’ lounge, behind him orange-felted billiard tables, leather recliners and a picturesque view into Darrell K Royal Stadium. Instead, maybe he’d be in Manhattan’s financial district selling stock and blowing whistles, surrounded by some of the tallest skyscrapers in the world. That’s what he wanted to do. Then he took the Series 7 exam, a grueling four-hour test mandatory for all entry-level financial professionals. “I didn’t make it,” he chuckles.

As the story goes, Orlando visited his old Pittsburgh high school that summer, connected with a recruiter from Penn there on a visit, and a few months later was at the Ivy League school coaching linebackers in what was then called a “limited earnings job,” says Orlando. “It was limited earnings and maximum work.” Orlando is now a handsomely paid football coach, in his third year as the Texas defensive coordinator having progressed up the career coaching ladder, from Penn to UConn to FIU to Utah State to Houston and now here. This week he’s the one with an unenviable task: slowing Jalen Hurts.

In a bonanza weekend of college football that includes four games pitting top-25 teams, the matchup between No. 6 Oklahoma (5–0) and No. 11 Texas (4–1) looms as maybe the most exciting of them all. Vegas sports books believe the teams will combine for more than 75 points, and that’s not so hard to fathom. The offenses and the quarterbacks are in the top 13 in both scoring and passing. Hurts’s numbers alone are enough for an entire team. He is averaging 404 yards a game and has scored more touchdowns (21) than 75 FBS programs this year. There’s no stopping him, coaches say. The only hope is to slow him down, and the simplest way to do that is through disguised blitzes.

That’s good, because that’s Orlando’s defensive style. “Best way to describe it would be Star Wars,” explains Texas quarterback Sam Ehlinger, who has battled Orlando’s defense during practice for three years. “Picture a Star Wars battle and that’s how it feels every single play. It’s very difficult. You never know where guys are coming from. They could be showing one look and it could be the complete opposite at the snap.”

Hurts is not invincible, as his numbers might suggest. In fact, Kansas—Kansas!—offered somewhat of a blueprint in slowing him down during a successful first half last week in OU’s 45–20 win. In this case, a successful first half is holding the Sooners to 21 points, but that is somewhat deceiving. One of their three touchdowns came after a 10-yard drive set up by a long punt return. The Jayhawks camouflaged their blitz packages, often getting pressure with four pass rushers and occasionally chasing Hurts out of the pocket with a fifth extra man. They sent at least five rushers on one-third of the snaps and pressured Hurts a half-dozen times during the first two quarters. On the broadcast, ESPN sideline reporter Tom Luginbill noted KU’s exploitation of the OU front. “As eye popping as the numbers have been, it’s been the offensive line that is concerning,” Luginbill said. “It’s been an area (coach) Lincoln Riley knows has to improve. They’ve got to be more physical.”

This is a play from Oklahoma's win over Kansas last week. Here you see how the Jayhawks disguised their four-man rush. Two linebackers faked a rush (first two red arrows) before the real fourth rusher attacked.

This is another example from Oklahoma's win over Kansas of the Jayhawks camouflaging their fourth rusher. Here, the linebacker delays his attack and, despite it being four vs. five on the line, breaks through.

Is this a crack in the Crimson and Cream armor? Yes, says one Big 12 assistant coach. “Not the skill positions but on the lines, I think Texas has the edge,” the assistant said. Like many quarterbacks, Hurts is at his best when he’s given time to diagnose a defense from the pocket and when he can make his read even before the snap. That’s why disguising coverages and pressure packages is critical. And so is possessing the ball offensively. In the first half last week, Kansas’s offense had two drives of more than five minutes. Hurts is good, but he’s not good enough to score from the sideline.

While he’s on the field, the onus falls on Orlando and what he calls his “unique” defensive scheme. He uses the same concepts as many other defenses, but he does so from an array of unusual formations. During an interview with Sports Illustrated, Orlando explains his defense in offensive terms. “It’s similar to an offense that says I like to run this run play, but I’m going to do it out of fly motion or unbalanced or trips and doubles,” he says. “When it hits the line of scrimmage, it is that same play, but the presentation can be different. Every week something might be tweaked here or there.”

The scheme has roots at Utah State. In 2013, Matt Wells was promoted to head coach in Logan, Utah, replacing Gary Anderson, who left for Wisconsin. As his defensive coordinator, Wells hired Orlando to replace Dave Aranda, who also left for Wisconsin and is now at LSU as the highest-paid coordinator in the nation. Wells wanted to keep Aranda’s defense intact, so Orlando learned it. “It was a scheme I didn’t want to go against on offense,” says Wells, now head coach at Texas Tech. “Odd front and even fronts, multiple blitz packages, false pressures, pressure packages, creepers, zone pressures, man pressures. It was a mix of all of it. It made life hard on the quarterback.”

Through the years, Orlando has put his own twist on the scheme, evolving it into the version today that helped revitalized a Longhorns defense that produced historic lows in the two years before his arrival. In the scoring-frenzy Big 12, Orlando’s units finished second and third respectively the last two years. The numbers aren’t as good so far this year (104 nationally), but the Longhorns have played two of the most high-powered offenses in college football: LSU and Oklahoma State. The faith is there. The foundation of this scheme is the same one in which Aranda used at Utah State to produce a top-15 defense in 2012, two years after it ranked 101. (In fact, Aranda, a college buddy of Texas head coach Tom Herman, strongly recommended Herman hire Orlando at Houston.)

Orlando is more aggressive with his scheme than Aranda, and he operates it with more variety. This year, for instance, he incorporated what’s called the “Cowboy package,” an eight-defensive back set built to match speedy spread offenses. “Might as well be 10 DBs because the two linebackers that stay in the game are fast and can cover,” says Ehlinger. In the coaching industry, Orlando is known for his aggressive and volatile approach. For instance, he often drops eight men into coverage or sends six rushing into the backfield. “He’s an aggressive guy by nature,” Wells says. “His defenses take on his personality.”

In searching for a defensive coordinator in 2013, Wells turned for advice to an NFL executive and a longtime college coach on the east coast. They each gave him two names with one in common: Todd Orlando. He flew to Logan to meet with Wells for an interview. “He’d never been west of the Mississippi, had no idea where Utah was,” Wells laughs. “Within 45 minutes, I knew I was going to hire him.” The Wells and Orlando families became close. In fact, Wells’s children recognize Orlando on television while watching Texas games. “That’s uncle Todd!” they’ll yell. Addison Orlando, now 6, is one of Wells’s favorites. He still refers to her by her nickname, one handed down from her father: the Little Berserker.

On the field and in the football facility, Orlando is a film junkie always sporting a serious scowl. Off the field and at home, he’s a goofy, fun-loving dad who everyone refers to as T.O., a nickname that a former colleague at UConn gave him during the height of NFL receiver Terrell Owens’s career. He’s the real T.O. Orlando is the other T.O. His players refer to him as a “genius” defensively, but he assures them of his real secret: He’s old. “He likes to say ‘You guys think I’m a genius, but I’m not. Just been doing it for so long,’” says UT linebacker Joseph Ossai.

Orlando is 48, ripe time for a potential head coaching gig. In fact, multiple outlets last winter reported that he interviewed for Temple’s vacancy. Randy Edsall was Orlando’s boss for more than a decade during their run at UConn, an impressive program resurrection that ended with a Fiesta Bowl. “I’ve had some people call me about him as a possible head coach,” Edsall says. “Does Todd aspire to be a head coach? I think he could be a really good head coach. Some people are satisfied being a coordinator and don’t want all that responsibility. It’s hard this day to be a head coach and call one side of the ball.”

Does Orlando want to be a head coach? “I’ve always said I wanted to be a head coach, but I’m not going to chase it,” he answers. “I’ve seen that before with other people and they’re chasing and trying to find this and that. I’m very happy here. Thing I look at with a job is (1) do you like your boss, (2) can you win a championship and (3) can you sustain success through recruiting.” Texas checks all of the boxes. He’s not necessarily itching to change jobs. After all, he feels blessed to be here. Remember, he was supposed to be a stock broker—for all the wrong reasons, he admits. “Stock market was big back then,” he says. “I was like, ‘Pretty good money.’” One-quarter of a century later, Todd Orlando is in the second year of a four-year contract paying him a year salary of $1.7 million. He’ll earn it this week. His goal: slow Hurts.