Everyone knows Nick Saban stacks his teams with the best talent.

Not his football teams, though that, too, is true, but his basketball teams—the pickup games he used to preside over before hip surgery three years ago ended his playing days. Whether it was three-on-three or five-on-five, half court or full court, the best players who showed up that day to play in the NBA (the Noon Basketball Association) found themselves on Saban’s team.

Saban not only picked the teams, but he was also the final arbiter on fouls and he controlled the scoring system (1 ½ points for a three-pointer and one point for anything else). This is how it was. Everyone knew this is how it was. And no one argued with how it was.

If you showed up late, you got an earful from the commissioner. If you didn’t show at all, you’d hear about it the next day. Just ask Jeff Purinton, now Alabama’s deputy athletic director, who once missed a game for a doctor’s appointment.

“Where the hell were you yesterday?” Saban asked him a day later.

“Doctor,” Purinton replied.

“Well,” Saban said, “you need to do that s--- on your own time.”

The NBA was serious business. Saban, his team always stacked with talent, rarely lost (sound familiar?).

So no one was really surprised when a young, athletic guy arrived on LSU’s coaching staff in 2004 and instantly became a regular member of Saban’s pickup basketball team. For 11 of the next 12 years, that guy, Kirby Smart, helped Saban win four conference championships, four national titles, 120 games on the football field (minus five vacated ones) and dozens on the basketball court.

They weren’t necessarily buddies (few are close enough with the coach to call themselves a “buddy”). They were, however, partners in constructing the greatest dynasty in college football history, like minds with striking similarities. Separated in age by 24 years, they shared a father-and-son relationship, a teacher-and-pupil bond.

And then, within months of their separation, the bond suddenly began to deteriorate. The relationship forever changed.

“There is no love lost,” says one of their former players.

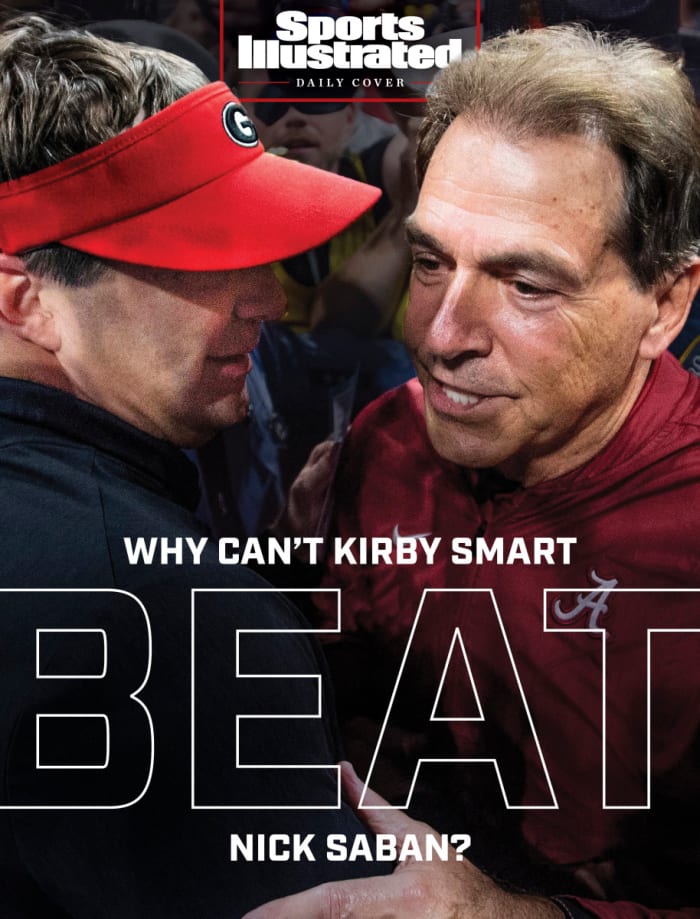

After winning the Orange Bowl, Smart and Georgia get a second crack at Alabama this season.

David E. Klutho/Sports Illustrated

When Alabama (13–1) and Georgia (13–1) play Monday night at Lucas Oil Stadium for the College Football Playoff crown, master meets apprentice for the fifth time in five years, this one another game of mega proportions. They’ve played for two national championships (2017 and ’21) and two SEC championships (’18 and ’21), and their regular-season meeting last year was a top-10 duel.

It is a remarkable stretch of collisions between arguably the two programs that develop and recruit better than any in the country. Since 2018, Georgia (20) and Alabama (16) have signed the most five-star rated prospects of any two teams—a combined 36, nine more than the next two, Clemson (14) and Ohio State (13).

Each program has strong administrative support, a tradition-rich history and is located in a football-crazed territory just 270 miles from each other within the nation’s most powerful league.

They are set up to win it all. But only one of the two coaches has.

“Kirby knows Nick better than anybody,” says Kirk Herbstreit, ESPN’s lead college football analyst, “and he just can’t quite get over the hump.”

Their four-game series features a truly stunning statistic. They’ve played a total of 240 minutes of football. Georgia has either led or been tied for 171 of those minutes, or 71% of the time. Despite that, Smart is 0–4 against Saban.

In the 2017 title game, the Bulldogs led 20–7 midway through the third quarter before Tua Tagovailoa’s game-winning touchdown on second-and-26 in overtime. In the ’18 SEC championship game, Georgia led 28–14 in the third quarter before an infamous failed fake punt from Smart turned the momentum. Last year, Alabama shut out Georgia in the second half to overcome a halftime deficit, and then a month ago, as touchdown favorites, Smart’s Bulldogs jumped out to a 10–0 lead before Alabama’s offense stunningly cruised to 41 points in a 17-point win.

These are the most recent daggers thrust into the gut of a Georgia program that is long suffering against Saban and on the national stage. The Bulldogs have lost seven straight against the coach. Over the last 19 years, Georgia, in search of its first title since 1980, has fallen one win shy of winning it all (2017), one win shy of twice advancing to the championship game (’02 and ’12) and one win shy of qualifying for the Playoff (’18).

Standing in the way three of the four times? Alabama.

“They've also been a problem and a thorn for any team they've played, [not only] ours,” Smart said. “We have that in common with a lot of teams.”

But when you’ve been so close so many times, when you’ve blown big leads, when you’ve stumbled in confounding ways, people start to ask a question.

“The knock on Kirby is he can’t beat Nick,” says Pete Jenkins, a longtime defensive line coach who works as a consultant for both men. “A lot of people said that about Coach [Bear] Bryant’s assistants. Well, none of the rest of us could beat Coach Bryant either.”

Smart has modeled his program almost identically to Alabama’s. He uses the year-round blueprint, says one former Saban assistant, which starts and ends with recruiting. The programs, Alabama and Georgia, remind one NFL scout of a professional team’s franchise: the organization, the structure and the practices—my goodness, the practices.

“They are each the most intense college practices we see every year,” the scout says.

The programs are so similar that one might get confused after spending time at one and then arriving at the other, as Jenkins has done before. “And the colors are similar, too,” Jenkins says, half-joking. “It’s like ‘Wait, whose practice field am I on?’”

What Smart has done is a rarity—an ex-assistant virtually copying his former boss’s program and replicating the success, almost.

“There’s been a lot of great coaches, but nobody has ever been able to work for the great coach and duplicate it. There’s not a lot of that,” says Kevin Steele, a man who has worked for both coaches and remains close with them. “Kirby has done that, short of a national championship.”

That obstruction has stood in the way of many pupils of the game’s greatest coaches. Mark Richt, Bobby Bowden’s former protégé, never won it all at Georgia. At Auburn, Pat Dye, a Bryant disciple, never reached the summit.

Can Smart hop over the hurdle before him?

“I wouldn’t call it a hurdle,” Steele chuckles. “It’s a mountain.”

In the early 2000s, Eddie Nuñez was a 20-something low-level LSU athletic department staff member when he learned about the lunchtime pickup basketball game that the football staff held nearly each day in the spring. Soon, he learned something else.

“It was the Nick Basketball Association,” Nuñez says, laughing.

Saban selected his team from those who showed up, and then everyone else formed the opposing team. This was not skins vs. shirts. It was Sabans vs. Schmucks.

A walk-on hoops player at Florida, Nuñez had skills, and it didn’t take long for Saban to realize it. The Nuñez-led schmucks beat the Sabans in back-to-back games. “Guys were walking out on the court for the third game and, all the sudden, he redoes the teams,” says Nuñez, now athletic director at New Mexico. “I’m now on Nick’s team.”

The games, played at LSU’s Pete Maravich Assembly Center, were intense and, at times, aggressive. There was trash-talking, and lots of it. “Everybody there had a mouth on them,” Nuñez recalls.

During Saban’s five years in Baton Rouge, the participants changed day to day and year to year. Will Muschamp, then defensive coordinator, was a regular. So were linebackers coach Mike Collins and running backs coach Derek Dooley. Line coaches Stacy Searels and Travis Jones often played as well.

In 2004, a new guy showed up. Kirby Smart left his graduate assistant post at Florida State for an unenviable job, coaching defensive backs for Saban—the position group with which Saban was most involved. Muschamp recommended Smart. The two worked together previously at Division II Valdosta State.

Not long after Smart arrived in Baton Rouge, he made his NBA debut.

“Coach Saban recognized the young, bouncing-off-the-wall Kirby and put him on his team,” Collins says. “And that was it.”

For years, Saban and Smart mostly swept the basketball court with everyone, a stretch that spanned that year in Baton Rouge, a year in Miami and then nine in Tuscaloosa. Their partnership extended to the golf course, too, where Saban and the visor-wearing Smart largely crushed the competition.

Smart was an O.K. golf player, the guy who tried to always outdrive you. Saban was a good player, even firing rounds in the 70s with ball-striking that he crafted each spring and summer.

Inside the football offices at Alabama, the young defensive coordinator served as a sponge of knowledge, absorbing Saban’s process as much as anyone. As the years passed, Smart felt less of Saban’s wrath than anyone. In many ways, some say, he evolved into the teacher’s pet. He got away with more things than any other staff member. Between Saban and Smart, there was a trust that grew.

“Nick trusted Kirby big time,” says Greg McElroy, quarterback at Alabama from 2007 to ’10. “Two coaches I never saw Nick get after were Joe Pendry and Kirby Smart.”

It wasn’t always like that. The first year they were together at LSU, there were hard times. Every week, Saban met with each position coach individually to watch film, back then recorded on videotape. If the tape, for whatever reason, didn’t work, you’d better have a backup ready.

“Kirby was nervous as a cat on a hot tin roof to make sure he had that beta [video backup],” Collins says, laughing.

Smart did a good enough job that the trust led to more responsibilities, such as being promoted from secondary coach to defensive coordinator in 2008, Saban’s second year in Tuscaloosa. Eventually, Smart went from captaining the defense to calling the defense.

Smart became a “sounding board” for Saban, says one assistant who worked with both coaches. The two spent more time around each other than any other coaches on staff.

For those who know both men, the relationship made sense. At their core, they are the same person. Former college defensive backs. Geniuses at attacking offenses. Fiercely competitive. Great talent evaluators. Persuasive recruiters.

“Kirby is so much like Nick in so many ways,” says McElroy.

Before leaving to lead his alma mater in 2015, Smart had been an on-field assistant for 11 years under Saban—still the second-longest run of any Saban assistant (the first is Bobby Williams at 17 years). How Smart lasted so long on the man’s staff remains a mystery for some. Saban is notoriously difficult to work under. He’s as demanding as anyone in the sport. Exhibit A: Since Smart’s departure six years ago, Alabama has employed four different offensive coordinators and three different defensive ones.

Smart passed on plenty of head coaching opportunities before Georgia called after the 2015 season. During that time, he saw many Saban assistants leave, become head coaches and fail. He waited on the right spot, says Steele. Georgia provides bountiful resources—financial, talent, facilities. You name it, they’ve got it.

At his new school, Smart kicked off things by using Alabama’s recruiting board, of which he had intimate knowledge, to his advantage. With the inside information, he showed prospects their true place within the Tide’s recruiting pecking order, a way to persuade them to join him in Athens. This is no revolutionary approach. In defending Smart, one person said, “Nick would have done the same.” That said, it rankled some in Tuscaloosa.

A few months later, the Maurice Smith situation in 2016 drove a wedge further between the two men. Smith, an Alabama defensive back, wanted to transfer from Alabama to Georgia. Even as a graduate, Smith needed a release from Alabama to move within the conference and become immediately eligible.

In a sometimes nasty battle that played out publicly, Saban refused to budge. Smart spoke out against the decision and so did Smith’s mother. In the end, the SEC stepped in, releasing Smith and triggering a discussion over intraconference transfer rules. In Athens, Smith flourished during his one season, serving as a team captain and recording 50 tackles, two interceptions and two forced fumbles.

“It was the straw that broke the relationship,” says one former assistant.

In social settings, Smart and Saban are cordial and respectful. In fact, during SEC coaches meetings, they often agree on legislation and policy. But their relationship is nothing like it used to be. And maybe that’s O.K.

“There were some things on his way out that the people in Tuscaloosa probably didn’t appreciate,” says Cole Cubelic, a former Auburn offensive lineman who now works as an analyst for ESPN and the SEC Network. “Since he left, it’s ‘I’m doing everything I can to win, and you are doing everything you can to win.’ It’s part of life.”

Smart's Bulldogs have given up more than 17 points just once this season: against Alabama in the SEC title game.

Erick W. Rasco/Sports Illustrated

This past June, two days after Father’s Day, Mississippi coach Lane Kiffin tweeted an image that playfully characterized the results of Saban and Smart’s on-field battles.

The image, clearly doctored, depicted a muscle-bound man in a tank top cradling a young child in his arms. Through the magic of Photoshop, Saban’s head was situated atop the man’s body and Smart’s head onto the child’s.

“Happy Father’s Day,” was scrolled at the top of the image, and Kiffin tagged both Smart’s Twitter account and the Alabama football team’s account.

The message was quite clear: There is one daddy in this relationship.

Smart isn’t alone. Before Alabama’s loss at Texas A&M this season, Saban had never lost to a former assistant, winning 24 consecutive games. On weeks when facing his old staff members, Saban grows even more serious. “He can get very intense about it,” former Alabama defensive back Shyheim Carter said a few years ago.

The feeling is mutual.

“Kirby wants to beat his ass,” says one former Alabama assistant who worked with both coaches. “I promise you, this is the best team Georgia has to do it. It’s probably eye-opening losing in the SEC championship game. Feels like this is the time. It’s hard to beat a team twice in a season.”

The result of Round 1, Alabama’s 41–24 win in Atlanta, surprised many coaches. For once, Georgia, not Alabama, had the talent edge. The Bulldogs’ defense entered the game straddling history. Smart’s crew had allowed no more than 17 points to any opponent.

Pound for pound, says one coach, UGA’s defense is the most talented unit in college football. Despite that, the Bulldogs were torched by Bama quarterback Bryce Young and his speedy receivers—536 yards, 25 first downs and seven (of 14) third-down conversions.

Bama’s offensive line, to that point the team’s weakest link, performed its best on the biggest stage. A Georgia team with 45 sacks this season had none. Cubelic says UGA is the most “calculated pressure team” in football, but on that day, the pressure wasn’t as precise. One Big 12 assistant says UGA defensive coordinator Dan Lanning chose not to blitz as much against Bama as he had all season. He got away from what made the unit so successful.

Offensively, Georgia then got too one-dimensional, says Herbstreit, and the game slipped away. The Bulldogs aren’t necessarily built to score in a frenzy through the air. Quarterback Stetson Bennett, a former walk-on turned starter, threw two costly second-half interceptions, one returned for a touchdown.

“In these big games, your quarterback is making a play or he’s not. The quarterback play has been the differentiator,” says Herbstreit.

But is there something more? A mental block? A psychological hurdle?

“I feel like that’s been present at times,” says Cubelic. “Football players, when it comes to the locker room, are very smart. If the coach is on edge and amped up more, those kids will see it. When we saw a coach get tight, we were like, ‘Aw s---.’”

Maybe Smart enters these games with too much intensity, suggests McElroy. Might the team instead need a more calming presence, a stoic man on the sideline and in the locker room—not the fiery, visor-throwing guy we often see? “He wants it so dang bad,” McElroy says. “If you press and want it and force the issue, those things can blow up.”

Herbstreit says the psychology of the matchup is “overblown.” Either way, Georgia finds itself in a peculiar situation. Despite losing to Alabama by 17 points a month ago, the Bulldogs are favored by a field goal ahead of Round 2. In addition to that, this one is for all the marbles, where Saban has thrived. He’s 7–2 in championship games, and, in his last six instances as an underdog, he is 5–1.

“It’s a recipe for disaster,” says one Power 5 assistant. “Alabama has the engine humming. It’s scary.”

Meanwhile, Smart takes the typical approach when asked about the series with his old boss. This isn’t about “he and I,” he said. “That’s for you guys to do.” Well, here we are. And here they are, Saban and Smart, meeting again as opponents after years of playing together—on the basketball court, on the golf course and on the sidelines.

Round 5 is here.

“Everybody can wonder, ‘Can Kirby beat Nick?’” says Herbstreit. “Put yourself in Kirby’s shoes. You respect the guy you grew up under and of course you want to win a championship for your alma mater. I don't think he’ll say it publicly, but there’s something more there. If that confetti comes down and it’s against Alabama and Nick Saban, there’s got to be something there.

“It’s like, if you beat your dad in something,” Herbstreit says. “He never let me win and I finally got him!”

More College Football Coverage:

• Expert Picks: Will Alabama or Georgia Win?

• Film Room: What UGA Must Do Differently This Time

• Saban's Coaching Pivot Pays Dividends in Title Run

• Is the SEC's CFP Dominance Bad for the Sport?