In Football, Moving Right Along Takes a Massive Effort

Imagine for a moment what it would be like organize and pack your family for a week-long stay to Miami, only to return and then do it all over again within 24 hours for another trip in the other direction to San Francisco.

Then imagine during it for roughly 300 people.

That’s what Jeffrey Springer and his staff pulled off last year when Alabama played in the College Football Playoff for the fifth straight season. In some ways it made the previous postseason’s destinations of New Orleans and Atlanta look simpler, but really very little of what they do is easy. Not even the home games.

“Last year was obviously harder than some of our other seasons,” Springer said. “There’s a lot of preparation that goes into what we do every year in the playoff.”

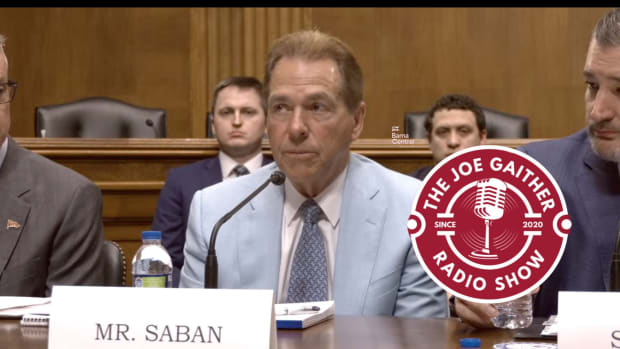

While Nick Saban may have what he calls "The process," and has arguably created the most successful program in college football history, Springer heads the massive operation under the Crimson Tide’s hood.

His official title is Associate Athletics Director, Equipment Operations, but few fully comprehend everything that entails. Equipment means a lot more than making sure 100 loads of laundry get done every week or making sure the quarterbacks have enough footballs to throw around.

First off there’s shoes. Alabama has a dedicated shoe room filled with everything from your standard cleats to whatever the kickers prefer, plus options for every possible surface the team might play or practice on. It’s like an entire Nike store crammed into the space where the bathrooms should be.

Then there’s the jerseys, both for games and practices, plus what the coaches wear depending on the weather. That includes short-sleeve jackets, long-sleeve jackets, sweatshirts, rain gear, slacks, polo shirts, undershirts, underwear, socks and any hats they might prefer. It’s the same for the trainers, weight-room, equipment, nutrition and medical staffs, among others.

Here’s the especially tricky part. Per its apparel sponsorship contract with Nike, Alabama has to order everything, and we mean everything, a year in advance. It’s a one-and-done thing, and the window for the 2020-21 football season closed near the end of September. The gear will all start arriving in March.

Think on that for a moment. Springer had to order everything for the 2019 recruiting class, from massive offensive tackle Evan Neal (6-7, 360 pounds) and speedy running back Keiland Robinson (5-9, 190), last fall before anyone signed his scholarship papers.

Alabama also has seven new assistant coaches this season, new analysts … you get the idea.

“The ordering aspect of it is huge in itself,” he said. “And then there’s the traveling and the packing for any game.”

Now you’re beginning to grasp the scope his job.

Springer has been at Alabama since 2011, when Tank Conerly retired after 23 years. He had the same position at Louisiana Tech with previous stops at The Citadel, LSU, Tulane and with the Miami Dolphins.

It was as an assistant equipment manager at LSU he first met Saban.

Springer has two assistants, Garrett Walker and Kyle Smith (while Jakob Walden is the equipment manager for Olympic sports) and an intern. For football there’s 15 students who get financial packages as full-time workers plus another 12 in the training group working their way up.

Combined they do everything from acquiring and distributing equipment, to getting deep grass stains out of the pants and setting up the locker rooms.

They also man practices. Each student is assigned a position coach, whom they help with everything from setting up drills, to holding up the play cards for the players. When each timed period ends, Saban expects everything to be immediately ready for the next drill so no moment is wasted.

(There’s a classic Saban story from before Springer arrived about a student making a bad mistake at practice and essentially being fired. The equipment staff kept him away from the coach for a couple of weeks and may have altered his appearance a little – depending on who is telling the story – before sneaking him back into the practice rotation. Saban didn’t let on that he noticed until near the end of the season.)

“There’s lots of different facets for what we do that a lot of people don’t realize about what goes into it and the time that it takes,” Springer said. “It’s 14 hours a day, seven days a week. Games are a lot longer than people think. A lot of people think you show up right before kickoff, they watch the game, as soon as the game is over they go home.

“A game for us starts at about 2 p.m. Thursday. We start packing.”

Alabama uses an 18-wheeler for a road game and a 26-foot box truck when it plays at Bryant-Denny Stadium – yes, it has to move everything from the practice fields a mile down the road. Since the team usually only has a walk-through on Fridays the trucks usually roll out shortly after Thursday’s practice ends.

On Saturday, the staff is in the locker room four hours prior to kickoff. They’re lucky to be done in the same time period after the game ends, and that doesn’t include the final cleanup and or any re-packing that needs to be done.

“So a game day for us is really a four-day process,” Springer said. “And then for a road game we have to travel.”

Last year’s playoff was especially problematic because of the quick turnaround, and television didn’t do the equipment staff any favors by scheduling the Orange Bowl as the night semifinal on Dec. 29, which was a Saturday.

Following the 45-34 victory over Oklahoma, the truck driven by Jack Vickers pulled out of Hard Rock Stadium at 2:30 a.m. ET and arrived in Tuscaloosa at 4:30 p.m. CT Sunday. With the staff having flown back (after riding a bus down), everyone was on-hand to immediately unload, wash anything that wouldn’t be replaced for the title game, re-stock and re-pack the truck.

The entire flip had to be done in 24 hours. Unlike the 15 hours it took the truck to reach Miami, the drive to San Francisco was at least twice as long, between 30 hours and three full days, with little margin for error. Alabama had to be completely set up and ready to go for the team’s arrival on Jan. 4, and first on-site workout at Stanford University the following day.

“You do whatever it takes,” Springer said.