Is UM Exposing Itself to COVID-19 Litigation? Heck Yes (And Heck No)!

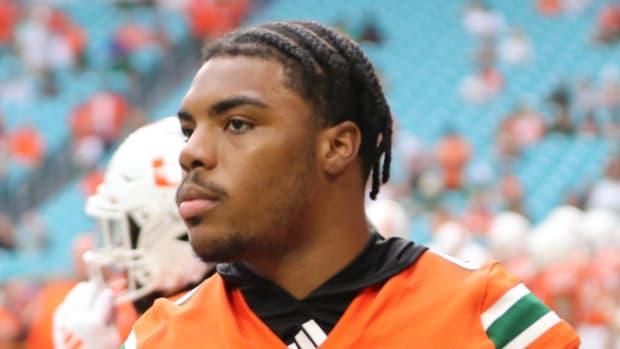

As the University of Miami continues its plans to play football in the fall some might wonder whether the school could be hit with a million-dollar lawsuit years down the line because one of its players sustains long-term effects from COVID-19.

The answer: It depends on which attorney you ask.

It also depends on something called sovereign immunity, a principle that basically insulates state entities (colleges and universities) from being sued and caps the damages if they are sued.

Sovereign immunity could be one reason the Big Ten and Pac-12 decided not to play in the fall (even though the Big Ten is re-visiting that decision) while the ACC, SEC and Big 12 are going forward. With damages capped at fewer than $1 million per occurrence in most states, public schools have little to fear financially.

In Florida, damages are capped at $200,000 per person and $300,00 per occurrence. In Mississippi, damages are capped at $500,000 per occurrence. Arkansas and California have no damage caps.

Whether each individual is regarded as a separate occurrence or all are enjoined as one occurrence would be a source of contention and probably left to the discretion of a judge.

The problem for the University of Miami is sovereign immunity applies only to public schools (Florida, Florida State, etc …).

Private schools such as UM are on their own.

“I think there could be very significant legal exposure,” Miami-based attorney Kendall Coffey, a founding member of Coffey Burlington, said of UM playing football in the fall.

However, a plaintiff (the player or perhaps a family member) would have to prove negligence or that UM failed to provide a reasonable amount of care, and that could be a difficult standard to meet, according to attorney Jim Waide, who represented ex-Mississippi State coach Jackie Sherrill in a recently-settled years-long lawsuit against the NCAA. Sherrill was accused of providing a car for one recruit and promising to help another recruit’s family. The NCAA eventually dropped the charges but Sherrill alleged the NCAA tarnished his reputation and prevented him from pursuing other coaching options.

Waide, founder of Waide & Associates in Tupelo, Miss., said he doesn’t think there could be any admissible evidence or any expert who could credibly testify the school didn’t meet a standard for negligence.

“Under the federal rules of evidence, you have to show there’s some scientific basis for any claims you make, some reliable scientific basis, and I don’t see how they could ever even get any admissible evidence the universities are negligent, because the doctors are so divided on it and there’s no scientific consensus.”

Waide added, “I guess the bottom line is I don’t think there’s any significant amount of exposure. There’s definitely not in Mississippi.”

But Miami and other schools are surely aware of the possibilities when it comes to long-term liability on ailments such as myocarditis and other heart issues that are potentially linked to COVID-19.

There’s no time limit on when the suit might come.

Debra Hardin-Ploetz sued the NCAA for negligence and wrongful death in 2017, which was 46 years after her husband, Greg Ploetz, played linebacker-defensive tackle for the University of Texas, and two years after he died from brain injuries, possibly as a result of CTE (chronic traumatic encephalopathy), a brain degeneration likely caused by repeated blows to the head.

Hardin-Plotez’s attorney, Eugene Egdorf, based near Houston, said in his opening remarks of the June 2018 trial that deceased Texas linebacker-defensive tackle Greg Ploetz took the risk that he could blow out a knee, separate a shoulder or sprain an ankle when he played college football. Nobody told him, Egdorf continued, that he was taking a risk of having permanent brain damage and dementia.

The case settled for undisclosed terms three days after the trial began. But it was a landmark event because it was the first civil case to make it to jury trial using the argument the NCAA didn’t do enough to protect football players.

As the University of Miami, as well as the ACC, SEC and Big 12, continue with their plans to play football in the fall, they’re surely aware of the possibility of unknown long-term effects of COVID-19.

They’re also aware attorneys are aggressively preparing for the possibility of lawsuits. One argument they might use is schools or conferences are asking players to accept the risks of COVID-19 when the risks aren’t fully known.

“Take what we’re seeing in college football,” Egdorf said. “If you’ve got a player, they’re getting told by President Trump, they’re being told by the SEC, they’re being told by their coaches there’s no real risk, and if you’re an 18-year-old athlete you’ve got a better chance of getting hit by lightning.

“And maybe that’s true. I’m not an epidemiologist. Maybe that’s true. But you’ve basically been told you’ve got zero to worry about. And so how does that ultimately play into whether you’re knowingly taking that risk? And there’s so much we don’t know yet. Is this heart thing really anything or not? Is lung damage permanent or not? Is immunity going to last or not? If you’re one of those nine kids at OU, are you in the clear or can you get it again in three months?

“So it’s kind of hard to have knowing acceptance of a risk when you don’t know the risk.”

Attorneys also say having a player sign a waiver might not be good enough for a school or conference to escape litigation.

“Many (players) would feel essentially forced to make a choice to return to the football field,” Coffey said, adding that players might think sitting out could adversely affect their scholarship or pro future, “and, of course would sign the waivers.

“And if the student contracted the virus and there were health consequences down the road I think the releases…would certainly be challenged, and I think a tidal wave of litigation could be expected.”

Egdorf, senior counselor at Shrader & Associates, said there’s another consideration with waivers--insurance policies.

“The thing that hasn’t been talked about is there are many insurance policies where if you have someone sign a waiver, your insurance policy becomes void,” he said. “I’m, as you know, a cynic about the NCAA. Do we think the NCAA, out of the goodness of its heart for athletes, told schools they can’t have waivers? Or maybe there’s something else to it?

“So I think that’s a big issue that’s out there, too. What is the impact on insurance policies?”

Attorneys being attorneys, they said they could find other possible defendants aside from the school, conference or possibly the NCAA.

“I haven’t thoroughly explored this,” Egdorf said, “but it occurs to me because the way a lot of coaches are paid these days you also have these booster clubs that are really how coaches get paid. So you take like Ole Miss, you take Arkansas, because they have a lawsuit going on with former coach (Brett) Bielema about whether they should actually have to pay his buyout.

“There’s other viable defendants that are going to make all these folks really nervous.”

Despite all that, Waide stands on what he thinks is solid legal ground.

“As far as suing the conferences if they expose athletes, you’d have to prove negligence,” he said. “You’d have to prove they failed to use reasonable care. Of course anybody can file a lawsuit about anything, but it would be extremely difficult to establish it, in my opinion, because the nature of the disease is unknown.

“It’d be somewhat like food poisoning cases. They’re very difficult and rarely won because you really can’t establish where they got it. In my opinion if somebody’s basing a decision on liability, if they were in Mississippi, I would say that’s not a very sound reason not to be doing it. Now if they’re basing it on they think the risk is too much for the kids, that’s different.”

And that’s the small opening that could expose UM and others to a lawsuit.

Some (schools) think they can manage the risk, Coffey said.

But: “There’s no doubt there’s a risk,” he continued. “And I don’t think anyone’s going to say there’s no risk, there’s no potential for adverse consequences.”