Homeland Security

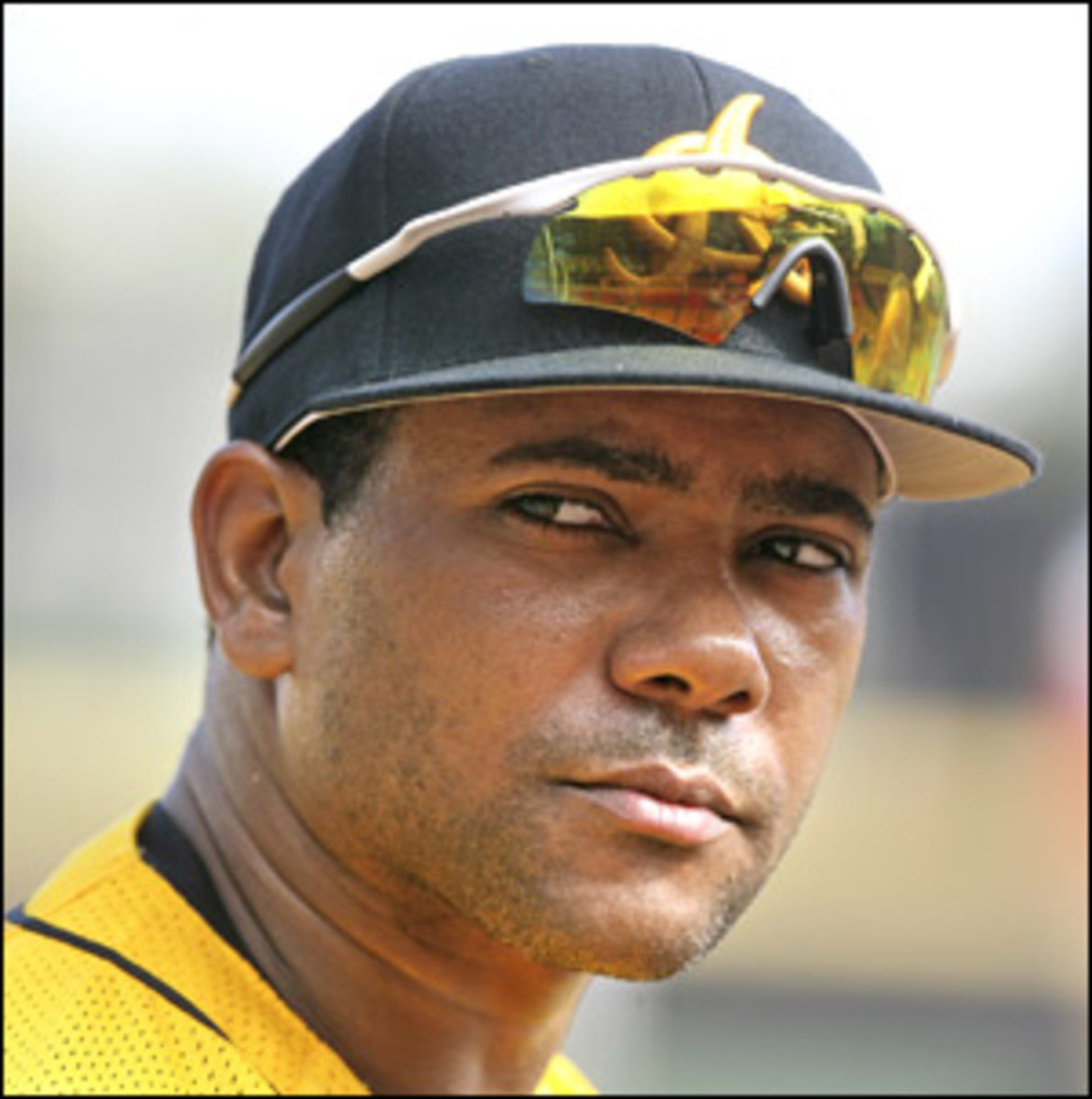

The forecast called for rain in Santiago, but the dark, heavy clouds were stalled on the horizon, allowing sunshine to illuminate the diamond at Estadio Cibao. It was Jan. 31, two days before Miguel Tejada was to lead the Aguilas, his Dominican winter-league team, against the Yanquis of Mexico in the opening game of Latin America's biggest baseball event, the Caribbean Series. The 31-year-old Houston Astros shortstop, four times an All-Star with the Oakland A's and the Baltimore Orioles, bounded up the dugout steps, still tucking in his yellow practice jersey as he ran to join teammates. After batting practice, he soft-tossed with a team assistant and then headed for the infield. When he wasn't taking grounders, Tejada swung an imaginary bat at an imaginary ball, as a third-grader might.

The lightness of his step, the ease of his smile, however, masked a grimmer picture. On Jan. 15 Tejada learned that federal authorities would be investigating whether he had lied when he told U.S. congressional aides in August 2005 that he never took steroids or any other performance-enhancing drugs. If charged with and convicted of perjury, he could face up to five years in jail. What's more, just hours after hearing of the investigation, he received word that his older brother Freddy had died in a motorcycle accident.

But here at Estadio Cibao his demeanor was undeniably upbeat. He nodded to stadium workers who called his name and waved to reporters before he spied New York Yankees first base coach Tony Peña stepping onto the field. Peña, a five-time All-Star catcher during his 18-year major league career and idol to many young Dominican players, walked over and grabbed Tejada firmly by both arms, then whispered in the shortstop's right ear: "Don't let anybody hurt you. There are a lot of people after you."

"Tony," Tejada whispered back in Spanish, "my heart is clean."

"I know you," Peña said, still holding him tightly.

"My heart is clean," repeated Tejada.

While Roger Clemens, Chuck Knoblauch and Andy Pettitte gave depositions last week to a House committee investigating steroid use in baseball, Miguel Tejada took infield and received a key to the city of Santiago. Tejada, however, remained very much on the minds of the House members -- and was in greater legal peril at the time than any of the players who were scheduled to testify at Wednesday's hearings.

On Aug. 26, 2005, Tejada, accompanied by his lawyer and an interpreter, was interviewed by congressional aides at a Baltimore hotel as part of a perjury investigation of his former Orioles teammate Rafael Palmeiro. Earlier that year Palmeiro, who had testified in front of Congress that he had never used performance-enhancing drugs, tested positive for the anabolic steroid Stanozolol. Palmeiro told a House committee that the positive test might have resulted from a steroid-tainted B-12 injection he had received from Tejada. During Tejada's hotel interview, an aide said to the shortstop, "You, I believe, testified to this earlier, but I just want to make sure, have you ever taken a steroid before?"

"No," Tejada replied.

More than two years later that statement was contradicted in the Mitchell Report, which contained 38 references to Tejada by name, including copies of two checks -- for $3,100 and $3,200 -- that he wrote to former A's teammate Adam Piatt in March 2003. In the report Piatt, who retired from baseball in '04, told Mitchell's investigators that the checks were payment for Deca-Durbalin and human-growth hormone that he had obtained from Kirk Radomski, the personal trainer and former New York Mets clubhouse attendant. (Last week Radomski received five years probation after pleading guilty to distributing steroids and money laundering.)

None of that mattered at Estadio Cibao, where Tejada has spent the last 14 winters. The fans pounding thundersticks at the Caribbean Series only cared that Tejada was there, playing for them. "The one thing that sets Miguel apart is the humility with which he's embraced his success," says Francisco Dominguez Brito, a Dominican senator and former attorney general. "Normally someone of his stature, with his fame and stardom, they don't come back to the Dominican Republic to play. All those young ballplayers have a lot of limitations in terms of education, and all of a sudden they find themselves with a lot of money and it makes them act out of control, but Miguel's never acted that way. He still plays in the D.R. like he's a rookie who still needs a job."

This is not the U.S., where congressional hearings and the bare-knuckled feud between Clemens and his former trainer Brian McNamee dominates the headlines. In Estadio Cibao, the myths die harder and ballplayers such as Tejada are unconditionally adored. The fans know the hardship Tejada endured growing up in the neighborhood whose very name sums up its challenges: Los Barrancones (the Obstacles). In 1979 Hurricane David, with its 150-mph winds that produced 30-foot-high waves, wiped out the Tejada home in the town of Baní and forced the family into the slums of Los Barrancones. That's the same dirt-poor barrio to which Tejada returns every off-season to deliver food. In 2004 he donated the money to build a 3,000-seat stadium in Baní. And one day after he buried his brother, Tejada was on the field for the Dominican Winter League championship, where the approximately 5,000 fans stood for every one of his at bats and screamed their support for the man they call El Pelotero de la Patria (the country's player).

Dominicans have an easy explanation for their collective shrug whenever the subject of steroids arises. They argue that just as stealing bread is not a crime when a man is starving, taking performance-enhancing drugs is acceptable when a player is desperate to get off an island where the poverty rate hovers around 40%. "What's wrong [in the U.S.]," says Fernando Mateo, president of Hispanics Across America, a New York-based advocacy group that lobbies Major League Baseball on Latino issues, "isn't so wrong there."

For baseball, fighting steroid use in the Dominican Republic has been like throwing punches underwater. The island that produced nearly 12% of the major leaguers on last year's Opening Day rosters and more than 20% of the All-Star starters last July, also produced one-third of the positive drug tests in the major and minor leagues in 2007. Though the Dominican summer and winter leagues -- where many of the country's top young prospects play even after they are signed by major league clubs -- have tested for steroids since 2004, the country's labor laws prohibited teams from suspending players who tested positive; violators were instead referred to counseling. But after intense lobbying by Major League Baseball, the Dominican government reinterpreted its laws: Starting this summer, players who test positive will face the same escalating 50-game, 100-game and permanent suspensions doled out by MLB.

Meanwhile, Tejada, who is not known to have tested positive in the Dominican or in the U.S., refuses to discuss the Mitchell Report or the perjury investigation, on the advice of his lawyers. "I'm preoccupied with baseball," he says. "[The charges] affect me a lot, especially because what I've done is based all on hard work. I know I'm going to come out of this clean."

Astros general manager Ed Wade, who obtained Tejada from Baltimore the day before the Mitchell Report was released on Dec. 13, expresses no buyer's remorse for his high-priced ($26 million for the next two seasons) acquisition and expects him to report to spring training next week. Though Wade acknowledges that Tejada could face punishment (commissioner Bud Selig, for one, has not ruled out suspensions for players implicated in the Mitchell Report), he defends the trade, saying, "He's a middle-of-the-order power bat at a position that's normally reserved for defensive guys. We just felt that if we had the chance to put him in the lineup with Lance Berkman and Carlos Lee, and with the additions of Michael Bourn and Kaz Matsui at the top of the order, that it would make us very productive."

Wade was in the crowd for Game 2 of the Caribbean Series when Tejada sent a seventh-inning pitch over the leftfield wall for his 12th career home run in Series play, breaking the record held by Tony Armas. Tejada circled the bases quickly, pointing skyward in memory of Freddy. As he headed toward home, his entire team -- and seemingly, a country -- waited with open arms.