Willie's firing evokes memories of odd exterminations from the past

It's never easy being told you're not wanted, that the organization is going in a different direction and that your services will no longer be needed. You can couch it in a thousand euphemisms -- all related to "philosophical differences," of course -- but it doesn't change the fact that you've just been fired.

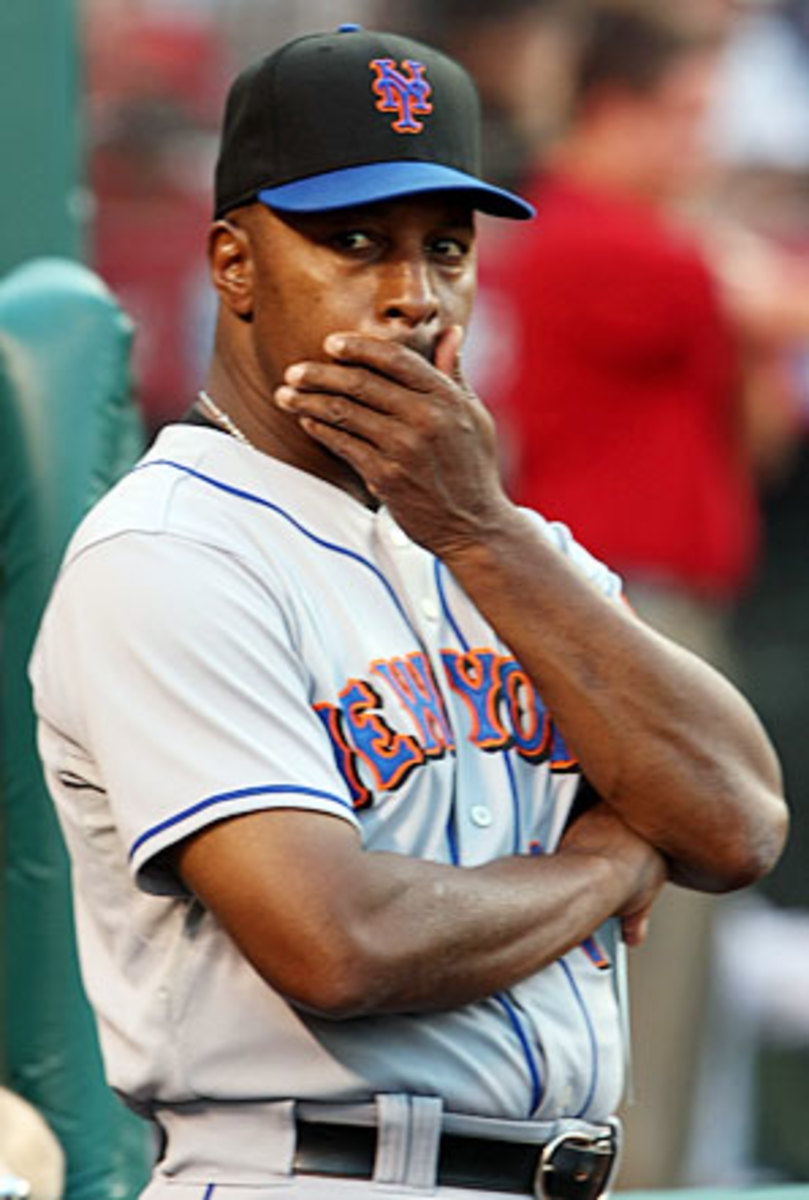

For a coach, losing a job is hard enough, but to learn about it on the road, after a win, at about midnight in an unfamiliar hotel, as Mets manager Willie Randolph did Monday night, that borders on offensive. To announce the firing at 3:12 a.m. ET, when all your fans are sleeping (and your local papers are rolling off the presses), is just plain cowardly.

But in sports, where job terminations are frequent, "coaches are hired to be fired." And although Randolph's dismissal was classless and crass, it doesn't come close to being the most outrageous firing in professional sports. In fact, it may not even be the strangest firing in New York baseball history. Remember that the Mets share the city with the Yankees and their longtime owner George Steinbrenner, who was notoriously trigger-happy with his managers throughout the 1980s.

From 1973-92, the Yankees managerial position had more turnover than the Baltimore Ravens' offense, with 13 different coaches occupying the spot during that period. Billy Martin took five trips on the Yankee managerial carousel; Yogi Berra, who was told he'd manage the whole 1985 season, win or lose, got the boot after 16 games, and the team went through three skippers during both the 1978 and '82 seasons.

Arguably the most memorable of those firings came in November 1980. After Yankees manager Dick Howser led New York to a 103-win season, Steinbrenner called an informal press luncheon to announce: "Dick has decided that he will not be returning to the Yankees next year. I should say, not returning to the Yankees as manager." He'd instead go into real estate development and scout from Florida. It was Howser's decision, Steinbrenner insisted. But when asked if he had been fired, Howser replied, "I'm not going to comment on that." He didn't comment, but everyone heard him loud and clear.

Steinbrenner's press conference, though, looks civil in comparison to the notable 2005 on-court near-firing of Ashley McElhiney. The former Vanderbilt hoops star became the first female coach of a men's professional basketball team in 2004 when she was hired to coach the ABA's Nashville Rhythm. Things were going well for the 23-year-old McElhiney until January 29, 2005, when team co-owner and CEO Sally Anthony told McElhiney to bench the team's star player Matt Freije, apparently upset her two partners had paid him $10,000 to play two games. The coach ignored the order.

As the game wore on, Anthony became so incensed with McElhiney that she eventually marched out onto the court during the middle of the game and fired her on the spot. Anthony had to be restrained by security and escorted off the court. McElhiney was "reinstated" as head coach by the other co-owners of the team but eventually resigned after the season ended. The Nashville franchise folded nine months later.

In truth, though, most firings aren't done quite so publicly. Sometimes they're done so privately that the coach barely knows it's happened at all. Take for example former Chicago Blackhawks coach Billy Reay, whose pink slip was literally shoved under his apartment door. The note came from owner Bill Wirtz, who dismissed the 13-year Chicago coach from the organization altogether just three days before Christmas in 1976. Or Joe Altobelli, who managed the Baltimore Orioles to a World Series title in 1983. On a Wednesday in June 1985, Orioles owner Edward Bennett Williams decided to fire the skipper. Yet Altobelli showed up to the offices the next day asking around, "Am I fired?"

And remember former Toronto Maple Leafs coach and general manager Punch Imlach? In November 1981, a month after suffering his third heart attack, Imlach learned he would no longer be needed by way of his parking spot. Maple Leafs owner Harold Ballard had reassigned it.

Three seasons earlier, Ballard orchestrated one of the most bizarre layoff ordeals ever when he fired head coach Roger Neilson twice in one season. In January 1979, Neilson was eating lunch at the Maple Leaf Grill when he overheard a radio announcer declare: "It's official! Neilson will be fired today."

"Everybody kind of looked at me. I just threw my hands up and said, 'I don't know,' " Neilson told SI in 1990.

Nothing even semi-official actually happened until March 1, when the Maple Leafs GM Jim Gregory told Neilson that the game in Montreal would be his last. The next morning, while collecting his belongings and bidding his players farewell, he told the beat reporters that the front office would announce his termination that afternoon. No such announcement came, as Ballard was having trouble finding a replacement. Three people had been offered the job, but each declined to take it. With a pair of games ahead and no coach named, Ballard proposed a deal. If Neilson wore a bag over his head and stood on the bench as the "mystery coach," a shameless (and in fact, shameful) publicity stunt, he'd be allowed to coach the game against Philadelphia. Neilson considered it for a moment but ultimately refused. The owner didn't seem to care and ultimately allowed Neilson to finish out the season; he coached the Leafs to a 34-33-13 record that year, the best record the franchise would have for the next 13 years. That June, Neilson was fired again (this time, on television).

Ironically enough, the "mystery coach" episode wasn't the last time Neilson would be unceremoniously fired. In 1999-2000, while coaching the Philadelphia Flyers, Neilson was diagnosed with multiple myeloma, a type of cancer that affects plasma cells. He was granted a leave of absence in February, and Craig Ramsay took over as interim head coach. After the first round of the playoffs, Neilson's doctors cleared him to return to the bench; Philadelphia GM Bobby Clarke, however, would not. Neilson wasn't even allowed to return as an assistant, Clarke said, and that summer Ramsay officially took over as head coach. To make matters worse, Clarke offered this explanation: "Roger got cancer -- that wasn't our fault. We didn't tell him to go get cancer. It's too bad that he did. We feel sorry for him, but then he went goofy on us."

Then there is the case of Elisabeth Loisel, the French woman hired to coach the Chinese women's soccer team. In March, she received her pink slip electronically through an e-mail that told her not to return to China for training because she'd been fired.

Some would argue that there's never a right time to fire somebody. But there certainly is a wrong time (3:12 a.m.). Oakland Raiders coach Mike White got axed on Christmas Eve 1996, and Chicago Bulls' Scott Skiles was dismissed as coach on the same day 11 years later. Glen Hanlon didn't have much to give thanks for last Thanksgiving when the Washington Capitals terminated his contract -- but, to be fair, Hanlon is Canadian.

More often than not, coaches know what's coming. In the case of Randolph, it was a matter of when, not if. And now that he's been relieved of his place on the hot seat, it's time for the Mets front office to explain this bungled firing -- one they hoped to bury in the news -- that won't soon be forgotten.