Before Scott Boras ruled baseball, he was a 24-year-old second baseman in Double A, and he was fast asleep. A knock on his hotel room door awoke him around 6 a.m. “Boras!” rumbled Cardinals minor league field coordinator George Kissell. “Get up!”

Boras’s mind raced. He was scorching the ball for the Arkansas Travelers. He had just come off a two-hit night. He was imagining his call-up by the time he turned the knob.

“Put some clothes on,” Kissell said. “We’re going to church.”

“George,” Boras pointed out, “it’s Tuesday.”

“I know,” Kissell said. “But I saw you play defense last night, and we’re going to church and praying that this workout’s gonna make you better defensively.”

There were better players throughout the minor leagues. But none of them would have as much of an impact on the sport as the guy who couldn’t field, didn’t hit for power and would never make the majors.

***

This winter alone, the Boras Corporation cleared more than $1 billion in contracts. That minor league second baseman has become the most prominent agent in sports.

These days, he is as consumed by the coronavirus pandemic as the rest of us. Even without games, he keeps himself—as is often the case—at the center of the baseball world. In March, he submitted to MLB a suggestion of a new postseason structure. Last week, he wrote a New York Times op-ed. On Monday, he told Sports Illustrated that he would urge the players' association not to accept the owners' latest salary proposal. And in between, he says, he is working 18-hour days consulting with epidemiologists and advising his clients. "I've lost my voice four times," he says.

The qualities that general managers see—and sometimes lament—now, his teammates saw four decades ago: the work ethic, the attention to detail, the ability to see what others don’t. Boras did not just become an agent (he prefers the term “baseball attorney”) after he failed to make the majors; he became a better agent precisely because he failed. It fueled his respect for just how hard the game is. It helps explain why he so relentlessly and easily paints his clients in the best possible light. A lot of people in baseball have reverence for the game. Boras has uncommon reverence for those who play it exceptionally well, because he couldn’t.

The greatest lesson of his playing career did not involve a glove or a bat. It was that the game he loved as a boy was, above all, a business.

***

Boras’s father, Jim, was a dairy farmer outside Sacramento, so young Scott spent long days milking cows and harvesting crops. Despite his dad’s exhortations to focus, the boy wired a transistor radio into his cap and listened to Giants and A’s games as he worked. One summer afternoon when he was about 14, he drove his tractor into a hole he hadn’t seen, snapped an axle and knocked himself unconscious. His father found the tractor on its side and his son passed out. He grabbed the radio, crushed it and only then set about reviving Scott.

Eventually the younger Boras made his way to the University of the Pacific, where he played center field for the Tigers and studied industrial pharmacology, taking classes in everything from anatomy to zoology. He would play a doubleheader on Saturday and then complete two three-hour labs, then do the same thing on Sunday. He planned to get drafted, enjoy a successful major league career, then get his J.D. and work in medical law.

But three weeks before the 1974 draft, he collided with another outfielder and tore the cartilage in his right knee. Major league teams could not get his medical information in time, so he went undrafted—or, as Boras puts it, he became a free agent.

He could have signed with anybody willing to offer him a low-level contract. He chose the storied Cardinals and reported to the rookie-level Gulf Coast League. In those days, most players signed out of high school, so between his age and his disposition, Boras carved out a role for himself as something of an assistant coach. Even though he was just a minor league second baseman, he did what he could to help the whole organization. He would memorize his teammates’ swings, then approach them if they began slumping: This is what you look like when you’re hitting well. He would take note of who was out late and encourage him to take better care of his body. Bob Kennedy, the farm director before Kissell, noticed and began assigning him players to befriend.

They got a kick out of him. One day in his second season, he got locker neighbor Nick Leyva’s attention.

“Watch these guys put their socks on,” Boras said.

“What?” Leyva said.

“Watch,” Boras said. “A right-handed guy will put his left sock on first and a left-handed guy will put his right sock on first.”

Leyva laughed. “Shut up.”

“This is the kind of stuff he came up with,” Leyva recalls now.

Boras’s mother, Betty, had begged him not to abandon his education, so he continued working toward his doctor of pharmacy degree. He would start school a month late and leave six weeks before the semester ended, so he spent much of his downtime studying. In Class A he asked his manager, Jack Krol, to proctor an exam. They’ll send you the test, Boras explained, and you’ll watch me take it.

Krol was skeptical. “It’s gonna cost you two six-packs of beer,” he said finally.

So Boras sat there for an hour and half, answering questions about neural pharmacology, while Krol slowly made his way through all 12 Budweisers, punctuating every few sips with a loud belch.

But Boras wanted to be thought of as a ballplayer, so in the clubhouse—not generally a bastion of educational excellence—he largely kept silent about his studies. He was mortified when his diploma was mailed to the ballpark. On interminable minor league bus rides, he wrapped copies of Playboy around his textbooks and got his homework done. He was certain no one noticed. Everyone did. And everyone was cracking up.

His Double A roommate, Jim Riggleman, laughs as he recalls the scene: “He was an academic surrounded by Neanderthals.”

He was also a good athlete surrounded by better ones.

“I thought I could run,” Boras says. “These guys could fly.”

He had expected to play center field but realized he wasn’t fast enough. So he joined a crowded Cardinals infield depth chart that included Héctor Cruz, Joe Edelen, Tom Herr, Nick Leyva, Ken Oberkfell and Garry Templeton—all future big leaguers.

Boras discovered he was also not really fast enough for the infield. He likes to joke that he taught righty Bill Caudill how to pitch: When Boras played third base, Caudill induced all the right-handed hitters to go the other way and lefties to pull the ball. When Boras played second, Caudill pitched righties to pull the ball and lefties to go the other way.

Finally, Boras grew tired of standing around. He confronted Caudill: What was the pitcher working on? What was he trying to do out there?

“Scott,” Caudill said, “We’re trying to win games. I’m trying to keep balls away from your glove.”

But he could hit. Even Templeton, a better player by every measure, admired Boras’s swing: short to the ball and punctuated by his quick wrists. Boras also possessed an unusually good eye. His Double A statistics have been lost to history, but in three years of rookie and Class A ball, he hit .286 and had a .390 OBP.

“Nothing excited me more than you took that 95-mile-an-hour fastball and you barreled it up and then you hit it in the gap—I didn’t have the power to hit it out—and then you stand there on second base knowing that feeling,” he says. “There’s a lot of thrilling things in life, your children being born and watching your children do things and certainly the people you work with and the people you work for, watching them succeed, that’s so rewarding, but on an individual level, that’s that feeling.”

***

After Boras’s second year in the minors, the players’ union filed grievances on behalf of pitchers Andy Messersmith and Dave McNally, contending that the one-year team option written into every player's contract expired if he did not sign a new deal. That winter, just over two years after Curt Flood’s lawsuit had begun chipping away at the system, arbitrator Peter Seitz agreed with the players, ushering in free agency.

For major leaguers. Minor leaguers were still beholden to their original clubs. During batting practice and on bus rides, Boras would remind his teammates that they lacked rights. “This is wrong,” he would insist.

His teammates mostly nodded and returned to whatever they had been doing. They were not particularly concerned about the ethics of the minor leagues; they just wanted to get out of the minor leagues. Boras had once been that way, too—just thrilled someone wanted to pay him to play baseball. Then he started paying attention.

He noticed cut day in spring training, when two dozen young men would trudge, sobbing, to their beat-up cars. Most of them had signed out of high school. They had no education. They had no backup plan.

As a child, Boras was so enthralled by César Chávez, the labor leader and civil rights activist, that his parents occasionally used to send him to his room when guests came over rather than endure yet another paean. Now he started to see baseball players as a labor force. He began to wonder whether he had to settle for all this. Heading into the 1977 season, he declined to sign his annual contract. He pointed out that his .295 average had led the Class A St. Petersburg Cardinals the year before and he’d been the only member of the club named to the Florida State League All-Star team. He felt he deserved more than the standard $1,250 a month. The team offered him $1,300. He accepted.

“That was my first negotiation,” he says.

A few months later, between games of a doubleheader, Boras was summoned to his manager’s office.

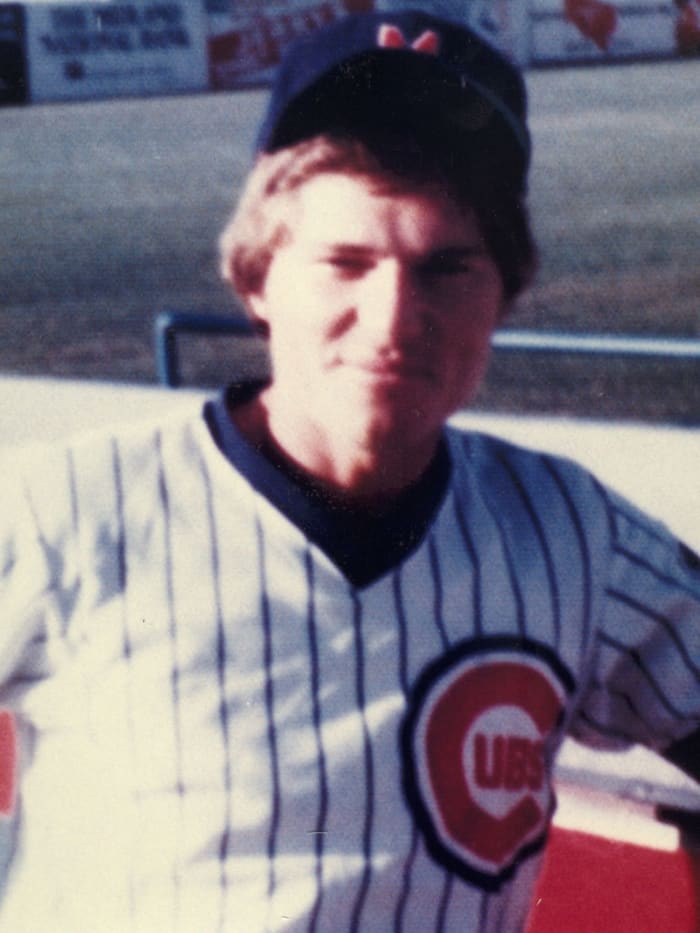

He was told he had been traded to the Cubs—whose Double A team, the Midland Cubs, his Arkansas Travelers were playing.

Boras was devastated. He had been “raised a Cardinal,” he likes to say, and there was no greater hit to his pride than to be sent to the enemy. He dragged himself into the other clubhouse and suited up for Game 2. Nobody could ever tell Scott Boras about loyalty in baseball again.

***

At every level, that old predraft injury continued to dog him. Between clutch hits and neural pharmacology tests, he hobbled to the training room in agony every eight to 10 days to have the bursa sac drained in his right knee. He was undergoing surgery after nearly every season. It was becoming clear to him that he could not go on in this way.

He had finished his doctor of pharmacy. The University of the Pacific had always been accommodating to his baseball schedule, so when he realized he’d miss graduation, his professors arranged an alternative: They invited Boras, his parents and some of his coaches to a private ceremony. Boras, dressed in his black cap and gown, accepted his diploma as three members of the student band played “Pomp and Circumstance.”

• South Side Hit Pen: Meeting Scott Boras

He and Kennedy, who had become the Cubs’ GM, had talked about Boras’s desire to go to law school after he retired. Now Kennedy suggested he give his knee a year to heal and get started on his J.D. I’ll keep you under contract, Kennedy promised, essentially funding the young man’s first year of school. They continued the charade for another two seasons—Let’s give it one more year—but Boras knew the end had come early in the spring of that first year.

He emerged from a building and the smell of freshly cut grass hit him. He staggered to a bench and tried to collect himself as his baseball career flashed before his eyes. He would never again stand there on second base knowing that feeling. He hunched on that bench and tried to come to terms with his overwhelming loss.

***

The greatest failure of Boras’s professional life led directly to his greatest successes. If he had become the major leaguer he wanted to be, he would never have approached a partner at his law firm one day and asked whether he could work, pro bono, on behalf of young players set to enter the MLB draft.

He has revolutionized his occupation. He does statistical analysis on his clients that rivals—and sometimes contradicts—that of the teams wishing to employ them. He can—and often does—make a case for almost any of the players he represents as a “generational talent.” And for years he has encouraged them to wait out the market. In 1997, the Phillies chose J.D. Drew with the second pick of the draft and offered him $3 million. Boras advised him to spend a year in independent ball. Twelve months later, the Cardinals took him fifth and signed him for $7 million. Last year, Boras client Bryce Harper did not sign until spring training games had begun. He netted $330 million over 13 years, the largest free-agent deal in North American sports history. All this makes him a polarizing figure in the industry. It also helps make his clients rich.

The legacy he will leave at the negotiating table is much greater than the one he could have left in the batter’s box, even if he had made the Hall of Fame. And at 5% commission, he is personally wealthy beyond what he could ever have imagined when he was making $1,300 a month. Still, he allows himself to wonder sometimes whether he wouldn’t rather have had it the way he dreamed: a decade or so in the majors, then a second act doing medical-malpractice work. If he could choose, which path would he take? He has an answer ready.

“Being a major leaguer,” he says immediately. His voice softens as he recalls those moments in the hospital, feeling the incision in his knee, praying this fix would hold. He knew he could hit, and he knew there was a place for people who could hit. “You might have been a bench player,” he says, “but you’d be in the major leagues.”

He pauses. “No,” he says finally, “Because to be able to stay in the game—how many people get to stay in the game for as long as I’ve been in it? Few people have done that. They may be in it for 10 years, 15 years, maybe 20, but that’s the real honor and privilege of this. I can say after thinking of it that I would choose the longevity and association of the game over a short period of time of playing in it.”

Even after negotiating more than $9 billion in major league baseball contracts, Boras can’t bring himself to walk onto a major league baseball field. He watches the clean way the ball bounces during batting practice and remembers the dusty diamonds where he once fielded grounders. He sees the crisp white jerseys his clients wear and reminds them, so frequently it almost reaches the point of comedy: You made it. He remembers that he didn’t. He can’t cross those foul lines. He hasn’t earned it.

Instead he catches a couple of Dodgers and Angels games a week, then steers the black Range Rover (he bought that one new) back to his Orange County mansion overlooking the Pacific Ocean. Still dressed in his Boras Corporation half-zip, he heads downstairs, into his 35-by-80-foot batting cage. Eleven p.m. has come and gone. His neighbors are heading to bed. All is dark around him. He reaches into a garbage can and grabs a baseball. He sets it on the tee. He begins swinging.