The Strike Zone Isn’t the Problem

Let me start this off by saying I really, really don’t want to be writing about the strike zone. Not during the playoffs, and especially not after the two late comebacks we saw last night.

Yet, here we are, talking about the strike zone, because some bad calls—one in particular—from last night have overshadowed everything that was so compelling about the conclusion of ALCS Game 4.

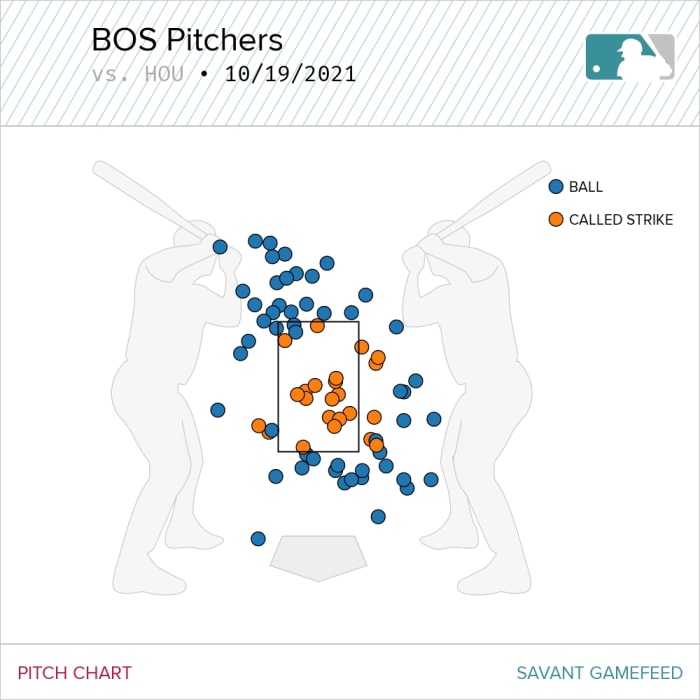

The score was tied, 2–2, in the top of the ninth inning at Fenway Park. The Astros had runners on first and second with two outs and Jason Castro at the plate. Nathan Eovaldi was pitching for the Red Sox, ahead in the count 1–2. Home plate umpire Laz Díaz’s strike zone was pretty rough all game, but his call on the next pitch was the inflection point that triggered the outcry.

This curveball appears to have caught the corner of the strike zone, but it’s pretty borderline. It could’ve gone either way, and had the rest of the game not played out like it did, we certainly wouldn’t be talking about this pitch. But after taking this pitch and fouling off the next, Castro ripped a go-ahead single to center field. From there, the Astros scored six more runs to cap off a ridiculous two-out rally in their eventual 9–2 win, which evened the series, 2–2.

For the most part, the strike zone is like the weather, field conditions and ballpark dimensions; it changes from game to game, or even within games, and is mostly out of the players’ control. Unlike many of baseball’s other uncontrollable variables, though, the strike zone is among the most visible and widely known aspects of the game.

Almost every broadcast superimposes a box graphic that represents the strike zone. If the pitch catches somewhere in that box, we expect it to be called a strike; if it’s outside the box, it’s supposed to be a ball.

That’s good information, and it certainly can be helpful for all of us as we watch and think about games. We use our understanding of the strike zone to evaluate talent, like when we consider a batter’s chase rate (how often he swings at pitches outside the strike zone) and a pitcher’s command. The most basic objective in baseball is to score more runs than the other team—batters are tasked with scoring runs; pitchers, preventing them. And the simplest way to do that is for batters to swing at hittable pitches (likely strikes) and for pitchers to make batters swing at pitches that are more difficult to hit (balls that look like strikes, or strikes that are closer to being balls).

Even without the in-your-face box, we all have a general understanding of where the strike zone should be. This is the definition of the strike zone as it appears in the glossary section of MLB’s website:

“The official strike zone is the area over home plate from the midpoint between a batter's shoulders and the top of the uniform pants—when the batter is in his stance and prepared to swing at a pitched ball—and a point just below the kneecap. In order to get a strike call, part of the ball must cross over part of home plate while in the aforementioned area.”

Except, this definition of the strike zone isn’t exact. The zone fluctuates because different batters are different heights, and kneecaps and mid-torsos are not pinpoint parts of the body.

Where specifically is “a point just below the kneecap”? The same question applies for “the midpoint between the batter’s shoulder and the top of the uniform pants.” Is it a strike when a breaking ball that nicks only a speck of the front right corner of the plate before sliding outside? Did it actually catch the corner?

These questions don’t even acknowledge that the vertical parameters of the strike zone have been intentionally altered over the years. At times, pitches as high as the top of the batter’s shoulders were considered strikes. The top of the knees have also been used as the lowest point of the strike zone on and off throughout the league’s history. During the stretches when the strike zone was shorter, umpires became more generous with its width, many of them turning to the Very Official Ball Length Metric System. If the pitch was one or two balls off the edge of the plate, it was considered a strike.

Really, the strike zone is an approximation, and it’s always been that way. The strike zone is meant to cover the area in which a typical batter can swing and expect to have a reasonable chance of hitting the baseball thrown by a typical pitcher trying to get him out. When the scales have tipped too much in the favor of the pitchers or the hitters over an extended period of time, MLB has altered the strike zone.

Sure, there are always going to be infuriatingly egregious ball-strike calls, but those are exceptions to the general rule: The strike zone is a location where most batters should have a reasonable chance of hitting the pitches thrown within its area. The 1–2 pitch from Eovaldi probably could’ve been considered within this area, based on this interpretation of the strike zone, but again, it’s borderline. There were plenty of other calls last night that were worse, but most of them followed a broad particular pattern: The strike zone was wider than the plate, so pitchers from both teams were getting strikes called that were one or two ball lengths off the edge. Díaz typically wasn’t calling strikes on pitches at the top or bottom of the box.

This is not a good strike zone, but it’s also not downright dreadful because it was similar for both teams. If you want to gripe about Díaz and the zone, that’s fair, because again, this isn’t good. But Eovaldi’s 1–2 pitch to Castro is not worth getting worked up about. If anything from that ninth inning, Red Sox fans should be livid about manager Alex Cora’s calling on mediocre-at-best lefthander Martín Pérez to get out of the ninth inning jam and keep it a 3–2 game. Boston’s offense could’ve come back from a one-run deficit. Instead, the Astros ripped Pérez and put the game out of reach.

O.K. That's enough about the strike zone. Let’s get into the rest of the day’s most important baseball stories and topics.

Have any questions for our team? Send a note to mlb@si.com.

1. THE OPENER

“The Astros’ season was circling the drain of inevitability when the smallest man on the field marched to home plate at Fenway Park on Tuesday. Down 2–1 in the game and six outs from a 3–1 deficit in the American League Championship Series, Houston needed oxygen. Fast.”

That’s how Tom Verducci sets the scene for the most important play from last night’s game, which happened an inning before the Eovaldi 1–2 pitch. Jose Altuve’s game-tying home run ignited the Houston hitters and helped even the series.

Read Tom’s entire story here.

2. ICYMI

Want to know more about the other exciting game from last night? We’ve got you covered.

The Rebirth of Cody Bellinger Resuscitates Los Angeles by Stephanie Apstein

The 2019 National League MVP floundered for most of the year. But when the Dodgers' season was slipping away Tuesday, he used his simplified swing to keep it alive and well.

Need a refresher on the rest of the NLCS? You can find that here.

Atlanta Won NLCS Game 2 By the Narrowest of Margins by Stephanie Apstein

The Braves just barely won Sunday's matchup against L.A. at Truist Park. The most important takeaway? They won.

Chris Taylor's Blunder Bungles Dodgers’ Chance in Game 1 by Stephanie Apstein

L.A. faced its best opportunity to win against Atlanta in the top of the ninth. Instead, the Braves walked off with a 3–2 win.

3. WORTH NOTING

Tom Verducci writes: How long can the Astros get away with feeding fastballs to Rafael Devers? They threw him 93% fastballs during the regular season. They have thrown him 90% fastballs in the ALCS (62 of 69).

Astros Pitches to Devers, ALCS (69 Total)

Astros Pitches to Devers, 2021 (182 Total)

Why would they do that? They follow the numbers. Devers is a great breaking ball hitter. He has the highest slugging percentage against secondary pitches in MLB (.587). He hits .298 against secondary (ranked sixth best) but only .266 against fastballs (94th).

Stephanie Apstein writes: The Dodgers won Game 3 of the NLCS, but they needed 5⅓ innings from their bullpen to do it. Walker Buehler, starting on extra rest after starting Game 4 of the NLDS on short rest, lasted only 3⅔ innings before manager Dave Roberts came and got him. Now Los Angeles needs to find a way to win one of the next two games and three of the next four with a taxed staff. Every pitcher on the roster has recorded at least two outs, and top relievers Kenley Jansen, Joe Kelly and Alex Vesia have pitched in every game. Julio Urías is scheduled to start Game 4 tonight, but his ability to go deep is unclear: He threw a high-stress inning of relief in Game 2. With a bullpen game looming on Thursday, the Dodgers will need him to stay out there for as long as possible.

4. WHAT TO WATCH FOR from Will Laws

After a thrilling couple of comeback-fueled contests last night, another doubleheader—perhaps the last of the year—is on tap today. This time, Astros–Red Sox starts things off at 5 p.m. ET with Game 5 of the ALCS on FS1. Then, Braves-Dodgers follows at 8 p.m. ET for Game 4 of the NLCS on TBS.

While Los Angeles will lean on Julio Urías, MLB’s lone 20-game winner this season, Atlanta is set to rely on a bullpen game. Braves relievers had recorded a 1.43 ERA during the playoffs entering the eighth inning of Tuesday’s loss, the best mark of any postseason team. Then, Luke Jackson was charged with four earned runs, matching the total number of runs charged to Atlanta’s bullpen in its first 25⅔ innings of postseason play. Can the Braves’ relief corps be trusted to regain its prior form?

Jackson and Tyler Matzek are the first relievers in franchise history to appear in each of the team’s first seven playoff games. If they show up again tonight, they will have pitched four times in five days, potentially ruling them out for Game 5. Meanwhile, Drew Smyly hasn’t pitched since the second-to-last game of the regular season, and Huascar Ynoa hasn’t been used since Game 4 of the NLDS, his postseason debut. Jacob Webb and Chris Martin each pitched a shutout inning in Game 2, their only respective playoff appearances. A.J. Minter improbably hurled a career-high three scoreless frames while making his first professional start in Game 5 of last year’s NLCS, but it’d be unrealistic to expect a repeat performance after he appeared in both Games 2 and 3, totaling 35 pitches. Who will Braves manager Brian Snitker trust in Game 4, and for how long?

5. THE CLOSER from Emma Baccellieri

For the Braves, it might seem easy to fixate on the pitch that doomed them yesterday, the one that Cody Bellinger drove out of the park for a three-run, game-tying shot in the eighth inning. Except … the pitch was fine. It was a fastball that was not just high but very high, almost a foot above the zone, and there was little reason to believe it would cause a problem. Bellinger had 86 at bats with a high heater this season. Do you know how many resulted in hits? Just eight. (That’s a batting average of .093.)

“Sad thing is, I would do the same thing again,” Atlanta reliever Luke Jackson said of the pitch after the game. “Good player put a good swing on it. Pretty remarkable.” He was right. It would make plenty of sense to do again. It made plenty of sense in the moment. But Bellinger, to his (considerable!) credit put a good swing on it, and he made all the difference.

That’s all from us today. We’ll be back in your inbox tomorrow. In the meantime, share this newsletter with your friends and family, and tell them to sign up at SI.com/newsletters. If you have any questions or comments, shoot us an email at mlb@si.com.