Houston's Worst Hitter Haunts the Braves in Fitting Potential Farewell to Original Baseball

ATLANTA - You would have to go back to 1937 and Margaret Mitchell to find the last time anybody in Georgia authored a story this perfect. On a majestic home run by Freddie Freeman, in his 14th and possibly final year in the Braves organization, Atlanta took a 5–4 lead into the fifth inning as uber-reliever A.J. Minter started the front leg of a bullpen relay race that would bring the Braves to their first World Series title in 26 years.

But this was Halloween night. And there was a knock on the door. It was Martín Maldonado, who came disguised as a Little Leaguer.

The Braves did not become World Series champions with a win in Game 5 Sunday. Their date with destiny was not so much gone with the wind as it was gone with a laugh. Maldonado, he of the .095 batting average this postseason, staged an epic trick-or-treat at bat. It was better than doorbell ditch.

“It turned the game around,” Astros hitting coach Troy Snitker says.

There was so much to admire about Game 5 on a grand scale. If this turns out to be the end of original baseball—the last game played in which all players must play offense and defense if the powers that be are bent on homogenizing baseball with the universal DH—this was a fitting breakup. The 9–5 win by Houston left a last reminder that baseball might never again be played with this intricacy. Astros manager Dusty Baker won the game by using nine players in the No. 9 spot in his lineup, including a pitcher getting a pinch hit and a bench player who had not driven in a run in 40 days getting the go-ahead pinch hit.

Goodbye, chess. Hello, checkers.

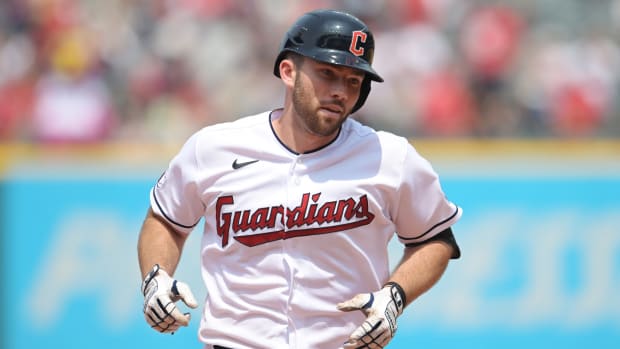

Astros catcher Martín Maldonado hits an RBI double against the Braves during the seventh inning of Game 5.

Brett Davis/USA Today Sports

It was not the end of the Astros’ core four. On a night in which Yuli Gurriel, Jose Altuve, Carlos Correa and Alex Bregman surpassed Derek Jeter, Bernie Williams, Tino Martinez and Paul O’Neill as the longest-touring band of four in postseason history (78 games), the Houston infielders made sure there is at least one more game before Correa departs via free agency. The four combined for eight hits, six runs and four RBI in an unmistakable show of veteran strength when staring into the abyss of elimination.

But nothing on this night was more remarkable than what Maldonado did. The World Series turned on ingenuity.

“That’s one of the things about this team,” Bregman says. “Nobody is scared. Nobody is afraid to fail. They try whatever they think will work.”

Braves manager Brian Snitker had this game exactly where he wanted it, which is upside down. Snitker has been on the kind of ridiculous roll that gets people kicked out of Vegas on suspicion of counting cards. No manager ever before dared start three rookie pitchers in a World Series. Snitker did it three days in a row, the last of which, Tucker Davidson, had not pitched competitively in 28 days and last pitched in the majors on June 15.

Of course, it “worked,” which is to say the Braves somehow survived Davidson to hand the 5–4 lead to Minter. That’s when Snitker finally hit on 16 and busted.

Minter wasn’t as sharp. Correa began the fifth by lining a cutter for a single. Yordan Alvarez, buried in a deep funk, struck out. Gurriel resumed the rally by stroking another of those Minter cutters for a single. After Kyle Tucker popped out, Snitker made the perfectly understandable decision of intentionally walking Bregman to have Minter dispose of Maldonado for the third out.

As Snitker settled on the idea, Maldonado came up with a counter one.

“I told the guys, ‘If I get the bases loaded, I’m going to stand on the plate,’” Maldonado says. “I might get hit with a cutter.”

Says Correa, “He said, ‘He’s throwing cutters in. I’m going to go Little League mode and get on top of the plate and make him feel uncomfortable.’”

Maldonado is a great defensive catcher. But he is such a poor hitter that one of his career comps is Cy Young, the pitcher. Only Maldonado, Young and two terrible hitting catchers, Bill Bergen and Jeff Mathis, ever came to the plate since 1900 more than 2,900 times and hit .212 or worse. His superior game-calling, receiving, throwing arm, baseball intellect and his nickname (Machete, for cutting down runners; you don’t easily dispose of that) are why he keeps getting playing time.

All Minter needed to do was punch out Cy Young’s hitting doppelgänger and the party in Atlanta was on.

He could not do it.

Maldonado stood nearly on top of the plate, affecting the position of a Little Leaguer given the take sign when the coach figures the only path to avoiding an out is a walk.

“No, I had no intention of swinging before two strikes,” he says.

From first base Bregman admired Maldonado’s ingenuity.

“I loved it,” he says. “It was awesome. The guy has tremendous baseball feel. Only he can adjust his plan and get on top of the dish and make you throw strikes.”

Minter threw a first-pitch cutter that nearly hit Maldonado. The next pitch, another cutter, was off the outside corner. Finally, Minter landed a four-seam fastball for a called strike, after which he barked something out in frustration.

“Martín told me that after the 2–0 fastball he heard him say something,” Correa says. “He said, ‘I think he cursed at me! I don’t know why. I’m just having a good at bat.’”

Minter threw another cutter. Too low. Now it was 3-and-1 and Minter knew he had to throw a strike. His next pitch was the worst of the five, another cutter that nearly hit Maldonado. The game was tied. The bullpen relay race, the Halloween party, the Margaret Mitchell sequel … all of it was on hold.

As Correa crossed the plate, he sidled up to Marwin Gonzalez, Baker’s choice to pinch hit who was looking for his first RBI since Sept. 20.

“'He relies on the cutter,’” Correa told Gonzalez. “Look for the cutter up the whole at bat. Hit cutter. Don’t look for anything else.’”

On the first pitch, Minter threw Gonzalez a first-pitch cutter up. Gonzalez dunked it into left field for a two-run single. The Astros led, 7–5. They would not be caught.

No more perfect postseason at home for the Braves. No more Snitker-doodle wins. No more invincibility for Minter. He entered Game 5 holding hitters this postseason to 2-for-20 on his magic cutter, and left having allowed three hits and a walk on ordinary cutters in a span of seven batters.

Astros catcher Martín Maldonado talks with starting pitcher Framber Valdez after he gave up a grand slam during Game 5.

Brett Davis/USA Today Sports

The exposure of his relief pitchers could be catching up to Snitker. Or maybe the Astros are just that wily. Maldonado is the baseball version of a fixer. He knows how to get things done in largely unnoticed ways, at least by fans. Teammates are awed by his knowledge.

Maldonado has made a first-inning mound visit in all but one of these five World Series games. He runs a game as if it’s his personal property. In the fifth inning of Game 5, for instance, he called timeout as Eddie Rosario came to bat for Atlanta with a runner at second. He walked out to the mound toward pitcher Phil Maton. Remember when your mom used to say, “Wait ‘til your father gets home?” Maldonado walks to the mound like the father who just got home. After a hard day of work. And bad traffic.

“Uh, he told me in very stern language how we wanted to pitch to him,” Maton says with a laugh. “He just wanted to remind me you have to pitch him like it’s 0-and-2 right off the bat. But it was, uh, a little stronger than that in terms of the language.”

Maton retired Rosario on a curveball Rosario tapped back to the box.

The next inning, Correa was in the on-deck circle when Maldonado called the bat boy over. He whispered a message in his ear he wanted him to deliver to Correa. The bat boy did as instructed.

“I just told him to remind him he is the guy who loves the big moment,” Maldonado says. “It was more like, ‘Have a great at bat.’”

As usual, Maldonado was behind the dish for all 151 pitches thrown by six Houston pitchers. Only one other team had won a World Series elimination game by using half a dozen pitchers: the 1972 Reds under Sparky “Captain Hook” Anderson in a 5–4 win over Oakland—another strategic spellbinder made possible only by the game’s original (pre-DH) rules.

Maldonado knocked in three runs in three varietals: an out, a walk and a hit.

“Yes, it’s probably the best game of my career,” he says, “especially because we were down like that. But this team has a lot of pride. And we love each other.”

Who knows where this World Series goes from here? It’s been like driving an unlit back country road on a miserable night as wet and dank as the one for Game 3: you can hardly see what’s immediately beyond the hood, but you know twists and turns are coming. It’s steering-wheel gripping time. On paper, the Braves should feel good about having Max Fried and Ian Anderson lined up for the two potential games. The Astros should feel good about getting the series back in their park.

What is certain is that the Braves’ clincher was put off in Game 5 by a light-hitting catcher who deserved the Best Costume award. With devilish creativity, and without taking the bat off his shoulder, Maldonado might well haunt Atlanta for more than just this night.

More MLB Coverage:

• Pearls Before Swing: Meet the Man Behind the Joctober Bling

• Soler's Go-Ahead, Pinch-Hit Home Run Shows Value of the Even Man Out

• The Greatest 21 Days of Brian Snitker's Life

• Why Does MLB Still Allow Synchronized, Team-Sanctioned Racism in Atlanta?