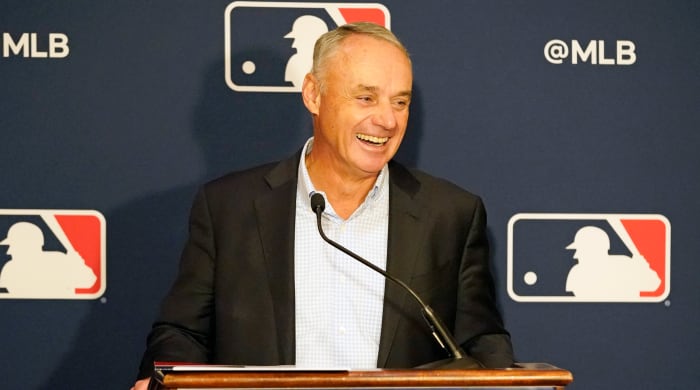

Don’t Be Silly. This Isn’t Rob Manfred’s Fault, Says Rob Manfred.

“In terms of any delay in the process, that’s a mutual responsibility of the bargaining parties. Phones work two ways.”

This was MLB commissioner Rob Manfred discussing the pace of labor negotiations during his press conference Thursday. It was a perfect representation of the spirit of the session: a line that was technically true—or, at least, not explicitly untrue—while being wildly, eye-roll-inducingly disingenuous.

Who’s to blame for the MLB lockout? Certainly not this smiling guy, says this smiling guy.

AP Photo/John Raoux

When the league began the lockout in December, after the expiration of the old collective bargaining agreement, it said the move was necessary to speed up the process of negotiating a new one. “Simply put, we believe that an offseason lockout is the best mechanism to protect the 2022 season,” Manfred wrote in his letter to fans. “We hope that the lockout will jumpstart the negotiations and get us to an agreement that will allow the season to start on time.” The result of that jumpstart? The league waited 43 days to return to the negotiating table with a response to the last proposal from the players. If MLB had an interest in establishing a regular cadence of bargaining, it did nothing to show it. All for Manfred to walk in front of the cameras Thursday and talk about the pace as a matter of “mutual responsibility.”

Which, yes, is true—bargaining takes both sides, and phones do indeed work two ways. But the side hosting the press conference Thursday was MLB, and, as its representative, Manfred had strikingly little of substance to say about what was actually happening here. Instead, the only message seemed to be that none of this can be his, the owners’ or the league’s fault.

Why do the players seem to have so little trust in him and the league? Not Manfred’s fault, Manfred said. “Most of the commentary that’s out there is tactical,” he replied. And what if there were players who actually were expressing themselves honestly and really did distrust Manfred? Well, naturally, that was on them. “In the history of baseball, the only person who has made a labor agreement without a dispute, and I did four of them, was me,” Manfred said, referencing the three agreements he worked on after becoming an executive vice president in 1998, and the one he has finished since becoming commissioner in 2015. “Somehow during those four negotiations, players and union representatives figured out a way to trust me enough to make a deal. I’m the same person today as I was in 1998 when I took that labor job. I just don’t know what else to say in response to that.” Perhaps to engage with the substance of the current criticisms? Or to consider whether the financial picture has shifted in a way that might make players more frustrated now than they were in past years? Nah. Of course not.

When asked about how that self-congratulatory remark on his negotiating record squared with the lengthy back-and-forth about how to start the season in 2020? “We had a contentious negotiation in 2020 over one issue in the middle of a pandemic,” Manfred replied. “The longer track record is we made four basic agreements without losing a game.” That is true. Yet the “one issue” in question here was how much players were going to be paid and for how many games: a huge, fundamental piece of any labor negotiation, and one that it seems weirdly insincere to categorize as “one issue.” But, then again, if the World Series trophy is “just a piece of metal,” I suppose player salaries are just “one issue.”

Finally, and perhaps most perplexingly, was Manfred’s answer when asked about the financial benefit of owning a baseball team. “We actually hired an investment banker, a really good one, actually, to look at that very issue,” Manfred said. “If you look at the purchase price of franchises, the cash that's put in during the period of ownership and then what they've sold for, historically the return on those investments is below what you’d get in the stock market, what you’d expect to get in the stock market, with a lot more risk.” Again—if this isn’t technically true, it can’t immediately be proved as obviously untrue, because teams’ financial books are generally closed. But given how franchise values have increased in recent decades … if owners really think they would be better off just investing in the stock market, well, they’re welcome to sell as soon as they can.

Sign up to get the Five-Tool Newsletter in your inbox every week during the MLB offseason.

So, to recap: The players who criticize Manfred are just trying to be strategic, and, if they actually mean it, that’s because they don’t grasp how well he works with the union. If they’re thinking about the contentious talks in 2020, they shouldn’t, because that was just one issue. And if you think owners are in the business of baseball because it’s an investment that has been shown to appreciate wildly? Ha! Don’t be silly.

Manfred said at one point that he was an “optimist” and believes an agreement will be reached before the lockout has a chance to cut into the season: “I see missing games as a disastrous outcome for this industry, and we’re committed to making an agreement in an effort to avoid that.”

If they don’t? Well, I’m sure you can guess where Manfred will assign the blame.

More MLB Coverage:

• What’s Behind MLB’s Latest Lockout Tactic

• The Start of the MLB Regular Season Is in Jeopardy

• Elite Defense Is Killing Ground Balls

• WAR Is Not the Solution for Baseball’s Labor Woes