Major League Baseball had a problem. It was 1968, A’s owner Charlie Finley had just moved his team from Kansas City to Oakland, and Missouri Senator Stuart Symington was threatening to revoke the league’s antitrust exemption, the carve-out that allows the sport to operate as a legal monopoly. To placate Symington, baseball’s 20 owners agreed to create the Royals, plus three other teams.

Walter O’Malley, the Dodgers’ owner and the most powerful man in baseball, suggested that one franchise go to San Diego. It was a clever bit of maneuvering by him. O’Malley arranged for the Dodgers’ team president, Buzzie Bavasi, to become a part owner, thus freeing up Bavasi’s job for O’Malley’s son, Peter. And as a market, San Diego came with some competitive disadvantages; as Bavasi would later say, it was hemmed in by Mexico to the south, the desert to the east, the Pacific Ocean to the west and Vin Scully to the north. O’Malley was basically giving his own team a neighbor to torment a dozen or more times a year.

More often than not over the next half century, that’s exactly what happened. During the 1970s, while the Dodgers carried hefty payrolls and saw the results, the cash-strapped Padres once asked players to wait three days to deposit their checks. In ’74 the team needed a $71,000 advance from the city of San Diego. Finances were so dire in ’92 that the team did away with its lobby Christmas tree.

It has not been all bad for the Padres: They twice made the World Series, in 1984 and ’98, although they were quickly dispatched by superior teams. But mostly, they have dwelled in the reality that San Diego, which Nielsen categorizes as the No. 27 media market in the United States, cannot match the revenue, and therefore the payroll, of such heavyweights as Los Angeles (No. 2) and San Francisco (No. 6), or even Phoenix (No. 11) or Denver (No. 16), its divisional rivals. And for years, the Padres’ payrolls reflected that reality; a three-year sample from a decade ago: No. 29 in 2011, No. 27 in ’12 and No. 25 in ’13, according to Spotrac.

But in August 2012, a group including Peter Seidler bought the team for $800 million. Seidler, a two-time cancer survivor, was undergoing treatment at the time; when he felt healthy enough, in ’20, he took over as principal owner and chairman. Since that day, payrolls have looked like this: No. 8, No. 5 and, entering March, No. 4. Upon signing 30-year-old third baseman Manny Machado to an 11-year, $350 million extension in late February, San Diego became the first franchise in history to employ two $340 million players. The Padres’ coffers have swelled to the point that they have gone from receiving revenue sharing to contributing to it.

As the Dodgers swept the Padres in August, Seidler referred to his neighbors as “the dragon up the freeway that we’re trying to slay.” And his team finished the regular season behind L.A., as it has 45 times in 55 seasons and every year since 2010. But in October the Padres unsheathed their swords. For the first time in franchise history San Diego beat Los Angeles in the postseason, a stunning three-games-to-one Division Series upset. “I think they were tired of hearing about us,” says L.A. first baseman Max Muncy. “They were tired of losing to us. And they went out and absolutely hammered us.”

Seidler, 63, calls that moment the best of his time in San Diego. O’Malley’s punching bag finally punched back. And that punching bag is now owned by O’Malley’s grandson. “I love that irony,” says Seidler.

This is what fans say they want: an owner who is willing to push his team to the financial limit. The Padres stand on either the cusp of greatness or the cusp of disaster. If most or all of the massive deals they have made work out, the team could become a juggernaut. But if the big-money players falter, eventually someone will come for the Christmas tree.

Over their first three years, the Padres averaged 7,054 fans per game in their 50,000-seat ballpark. In his book Lords of the Realm: The Real History of Baseball, John Helyar describes a moment when Bavasi learned that a former player was on his way to ask for a loan: “Bavasi groaned and asked [Padres trainer Doc] Mattei where he might hide. ‘You might try the ticket windows,’ he said. ‘Nobody’s ever there.’ ”

It was a different story at the home of the Padres in February. As she wound through the right field concourse at Petco Park during FanFest, a Mister Softee vendor begged the crowd, packed in tight enough to draw ire from the fire marshal, to part. She inched forward, a step or two every few minutes. Finally she gave up, her vanilla-milkshake mix beginning to curdle in the San Diego sun, and took it all in.

Every Padres star attended the event, as did, it seemed, every fan who ever tuned into KWFM. The Padres maxed out FanFest—150,000 free tickets distributed; 48,000 people in attendance; the event extended an hour to accommodate the lines of people snaking around the ballpark—and capped season-ticket sales this winter at 24,000, all due to what they call “unprecedented demand.” Players had spent the previous day bopping around the city, making unannounced appearances. Ace Joe Musgrove played pickup basketball at the Monarch School, which educates unhoused kids. Closer Josh Hader tended bar at Bub’s. Left fielder Juan Soto laughed as he declined to hold a snake at a Petco store.

This is the scene Seidler says he envisioned as he began writing checks. Ten years and $300 million for Machado in 2019. Fourteen years and $340 million for right fielder Fernando Tatis Jr. in ’21. Five years and $100 million for Musgrove in August. Eleven years and $280 million for shortstop Xander Bogaerts in December. Six years and $108 million for righty Yu Darvish in February. That $350 million extension for Machado. The Padres also traded for Soto last year, taking on two and a half years at somewhere north of $50 million.

All owners say they want to win. Not all owners carry a projected luxury tax payroll above $270 million. (Perhaps relatedly, not all owners hear the crowd chant their name, as San Diegans did when Seidler took the stage for a Q&A session at FanFest.)

“There’s never been a major championship in this city, ever,” Seidler says. “We listen really carefully to our market, and what we believe that we heard is, If you give us something to support, boy, we will rise up. We will be there in force. . . . We thought, If we make aggressive moves, our community will respond equally aggressively. And it’ll make sense and it’ll help us win. And that’s what we’re seeing.”

Perhaps in part because of his family’s legacy—until Peter O’Malley, Seidler’s uncle, sold the Dodgers to News Corporation in March 1998, the family had owned the team for 48 years—Seidler tends to take the long view. He is especially fond of what the Padres call “statue contracts,” or deals that secure players for double-digit years, because he believes that consistency matters to the community. “The fans know that they’re going to be able to see a lot of these players to the end of their career,” he says. And he feels confident the team will be able to withstand those financial commitments. He likes to tell people, “The business of baseball is good.”

Some of his fellow owners do not appreciate Seidler’s spending spree. “[San Diego] puts a lot of pressure [on us],” Rockies owner Dick Monfort told The Denver Post in January, before his team opened spring training, a season after losing 94 games, with a projected $156 million payroll. “What the Padres are doing, I don’t 100% agree with, though I know our fans probably agree with it. We’ll see how it works out.”

To be sure, the Padres find themselves in an unusual situation: San Diego is the only city with an MLB club as its only men’s major professional sports team. It also boasts 1.4 million residents, many of whom harbor Los Abandonment issues: The NBA’s Clippers spent six years in San Diego in the 1970s and early ’80s before decamping for L.A., and the NFL’s Chargers broke even more hearts when they followed suit in 2017 after 56 seasons. This city is desperate for a winner to embrace, especially at the expense of its neighbor up the coast.

Watch Padres games live with fuboTV: Start a free trial today.

Still: Baseball teams make money. If they didn’t, their owners would sell them. So why doesn’t every so-called small market operate as the Padres do?

“I think they all can,” says Machado. “I think they all have the means for it, but ultimately it’s if they want to win. Peter’s shown the interest that he wants to win, and it’s showing.”

Seidler (left) has given GM Preller all the resources to build a winner in San Diego.

Matt Thomas/San Diego Padres/Getty Images

Monfort was surely speaking more from self-interest than from altruistic concern, but a note of caution is fair. Gigantic deals come with gigantic risk.

Seidler does not have to look far for evidence of the perils. The Padres first used the term “statue contract” when the team was negotiating with Tatis in early 2021. At the time, he was a budding superstar who ranked seventh among shortstops in outs above average, led all hitters in exit velocity and finished fourth in NL MVP voting. He was also a 22-year-old who had played less than a full season. A photo of him flipping his bat graced MLB: The Show 2021. The season after he signed the deal—the third-largest extension in major league history at the time—he finished second in the league in WAR and third in MVP voting. He was on track to be the most iconic Padre since Tony Gwynn.

But that winter, Tatis broke his left wrist in a motorcycle accident. He was on a rehab assignment at Double A San Antonio, days away from returning to the majors, when he was suspended for 80 games after testing positive for clostebol, an anabolic steroid. He initially claimed he had taken medication for ringworm he contracted while getting a haircut, then spoke more vaguely about a skin infection. San Diego officials and teammates publicly blasted his immaturity.

But that disappointment did not change the Padres’ attitude about long-term contracts—nor did it change their opinion of Tatis’s talent. According to someone familiar with the team’s thinking, executives only briefly considered trying to void his contract. (Player contracts bar dangerous activities such as riding motorcycles.) He’s still worth it, they decided. They intend to move him to right field when he returns after serving the 20 games remaining on his suspension.

Bogaerts’s $280 million deal kept the Padres’ spending ways apace this offseason.

Matt Thomas/San Diego Padres/Getty Images

Standing in his place at shortstop will be Bogaerts, who can still barely believe the contract he signed. He did “not at all” expect anyone to offer him 11 years, he says, but the Padres wanted him, and they wanted to separate themselves from his other suitors. They offered a similar deal to shortstop Trea Turner, who chose the Phillies, and were prepared to go even higher to right fielder Aaron Judge, who returned to the Yankees. Padres players checked their phones with glee all offseason, never knowing what general manager A.J. Preller’s next move might be.

Preller downplays the binge. “Even with the higher payroll number, we probably have the most flexibility we’ve had,” he says. Translation: Because the highest-paid players have mostly performed well, they are tradable in case of emergency.

And there might well be an emergency or two on the way: Soto is due to become a free agent in 2025. The Padres acquired him last summer after he rejected a 15-year, $440 million extension offer from the Nationals; a deal to keep him in San Diego would likely exceed $500 million. And just up the road in Anaheim, two-way superstar Shohei Ohtani is slated to be a free agent after this season. He might command even more. The Padres are thought to be in on both players.

Can this last forever? Will the Padres run out of money? No less an authority than commissioner Rob Manfred asked that question as spring training opened: “The trick for smaller markets has also always been sustainability,” he said. “Hats off to Peter Seidler. He’s made a massive financial commitment personally to making this all happen. The question [becomes]: How long can you continue to do that?”

Seidler says, “I don’t think I use the word sustainability. People do. . . . I know, as much as you can know these things, that we have everything we need to put a winning team on the field every single year.”

He declines to be specific about his finances, but he points out that he’s been a businessman for a long time: He opened his investment firm, Seidler Equity Partners, in 1992; it now manages some $3.5 billion in assets. Between his personal wealth and the furor around the team—the Padres have seen unprecedented demand for sponsorships in addition to tickets—he believes he can make the math work.

Many in and around baseball question how long the Padres can maintain their high payroll.

John W. McDonough/Sports Illustrated

So far, Padres players are thrilled. “That’s how you’ve gotta be if you want to f---ing win,” says Musgrove, who grew up 20 minutes northeast of Petco Park and as a child watched a lot of f---ing losing. “You can’t compete with teams like the Mets and the Dodgers and the Yankees, who are going out and spending millions and millions, if you’re not [on that level]. You can go on runs like Cleveland did, but the realistic ability to be there year after year and compete for that spot—it’s tough to keep up.”

Which brings us back to the Dodgers. The Padres try not to make them too much of a focus, but “we know that we gotta go through them,” Machado says. And suddenly, they believe they can. Their lineup looks stronger than the Dodgers’, their rotation deeper, their bullpen more electric. And after last October, the Padres know what it takes.

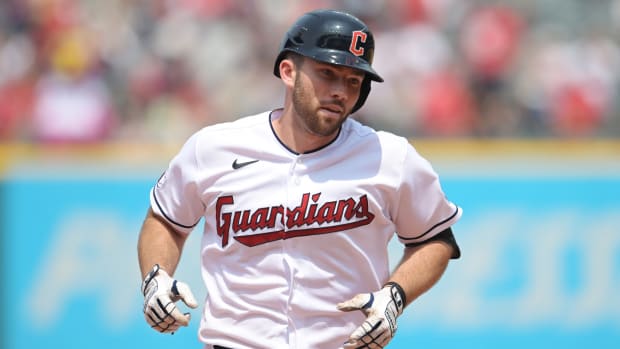

“Knowing how to win is completely different than thinking you can win,” says Muncy. “They’re starting to learn that over there.”

Meanwhile, the Dodgers are paying the Padres the ultimate compliment: They acknowledged they have to go through them. L.A. officials last year were dismayed that the young, hungry Padres exuded more energy during that NLDS than the veteran Dodgers. L.A.’s shift toward prospects this year was, of all things, partly an attempt to keep up with San Diego. Walter O’Malley, what have you done?