The Most Heated Rivalry in College Basketball

The basketball rivalry between Duke and North Carolina is the fiercest blood feud in college athletics. To legions of otherwise reasonable adults, it is a conflict that surpasses sports; it is locals against outsiders, elitists against populists, even good against evil. It is thousands of grown men and women with jobs and families screaming themselves hoarse at 18-year-old basketball geniuses, trading conspiracy theories in online chat rooms, and weeping like babies when their teams - when they - lose.

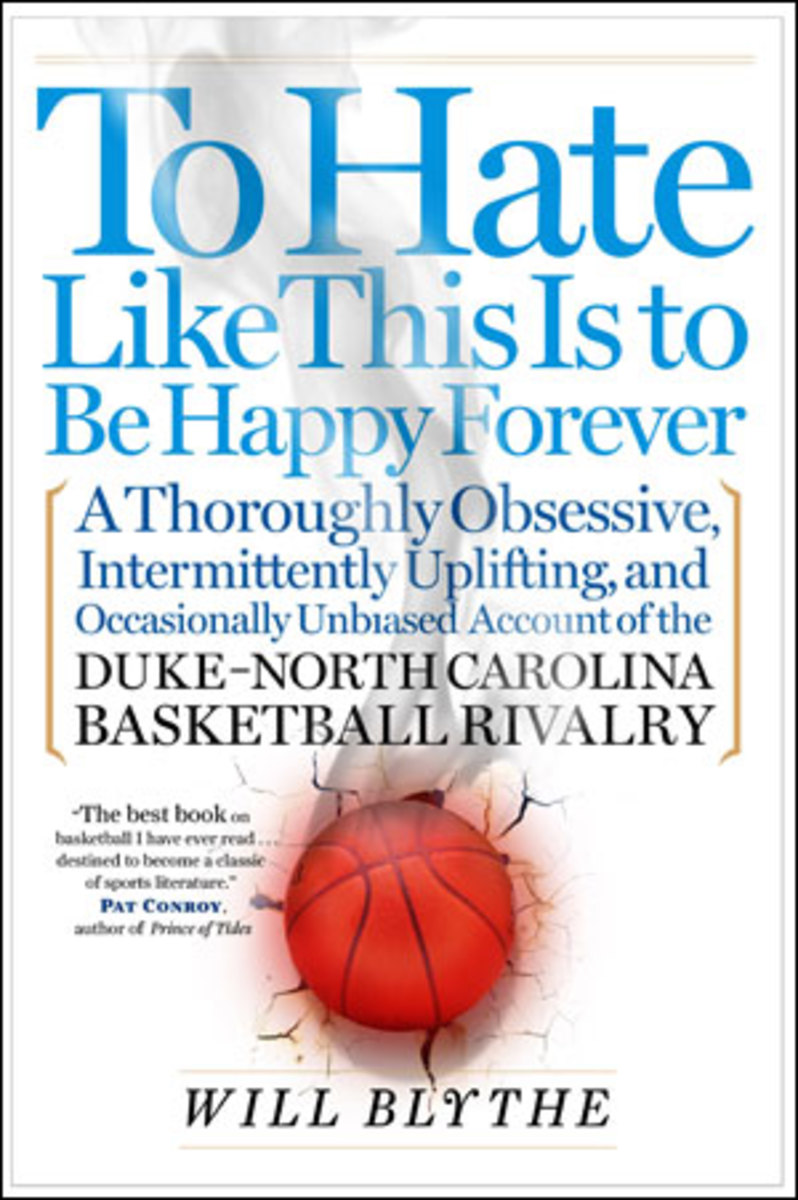

What makes people care so much? The answers have a lot to do with class and culture in the south, and in his book, To Hate Like This is to Be Happy Forever (HarpenCollins, Feb. 2006, $24.95), author Will Blythe, a lifelong Tar Heels fan, expands a history of an epic grudge into an examination of family, loyalty, privilege, and Southern manners. The following is an excerpt:

The morning after I saw Mike Troy, I logged on to the website Inside Carolina for the first of several daily visits. It was the place where you could always go where everyone knew your fake name. Coffee in hand, I clicked on one thread after another, a hunter-gatherer in search of big games. I liked screeds, jeremiads, vindictive attacks. I liked shoot-outs between posters. I liked accounts of pickup games, recruiting gossip, and the never-ending assault on Duke University. If I had ever thought myself consumed in a most unseemly fashion with the Duke--North Carolina rivalry, I had finally found a place that made me feel like a dull elder statesman who parsed his sentences carefully and made a career out of avoiding controversy. The guys here wielded flamethrowers.

The prototype for the site had been built in 1996 by Ben Sherman, then a 16-year-old Carolina fan in the unlikely outpost of Newtonville, Massachusetts. He couldn't quite say what resulted in his having a crush on a team eight hundred miles south, but it emerged at about the same time as consciousness. "I hated Danny Ferry as soon as I started watching TV," he said. Naturally, he applied to North Carolina for college, where, as was so often the case with out-of-state applicants, even ones with good grades and high test scores, Sherman was rejected. He headed south anyway, to the University of Richmond, where in August 1998 he established a new base of operations for his Carolina website. The site had since evolved into a sort of vast cybernetic encampment, in which hardcore Tar Heel fanatics could gather to express their tribal affiliations.

"The way I look at it, it's a grander scale of when me and fellow Carolina fans get together, just screaming and yelling and throwing things. After the game, if you're pissed off . . . you vent. And a message board is a place to vent. It's so ecstatic after the win, so devastated after the loss. Sometimes it boils down to the chance for somebody to say: I hate this."

The Duke--Carolina rivalry burned perpetually on the Inside Carolina board like one of those underground coalfield fires in western Pennsylvania. There was no way to put out the flames. Hardly a day went by without two or three new Duke threads sparking up, so many that some posters complained about the board's obsession with the Blue Devils. It wasn't that the complainants wished to defend Duke -- to the contrary. Instead, they felt that such an obsession was demeaning to North Carolina. Such threads ceded too much psychic territory to Duke. They actually enlarged the school by spending so much time cutting it down to size.

In the hours I spent each day rummaging around the site, I'd gotten to know the personae of many posters. Ironically, one I'd come to appreciate was a Duke supporter, Lpark, everyone's favorite Blue Devil for his generally balanced and occasionally self-deprecating commentary on both programs. What was he was doing so far away from home, spending hours a day on the Carolina message board, suffering the jibes and taunts of his declared enemies? I couldn't say. Penance, maybe.

But from time to time he appeared just sane enough that the flaming partisans of Inside Carolina envisioned a potential convert. They were always trying to lure Lpark into the light -- the light blue, anyway. They wanted to see him healed of his Duke affliction, purged of the demons that must have lived inside of him. Occasionally, Lpark got mad and punched back, as he did in one exchange: "You talk about Dahntay's lip snarl," he wrote, referring to the much-hated Blue Devil Dahntay Jones, now playing (rarely) for the Memphis Grizzlies. "How about Jerry Stackhouse's head bobs, Rashad McCants's primal screams, every face Vince Carter made after a dunk. What's the difference? The answer . . . the shade of blue."

This was entirely too reasonable a response, and thus doubly annoying. He accused the IC regulars (who tended to descend on Lpark for an oldfashioned street mugging when he got a little too uppity), of "taking any situation [in regard to Duke] and tagging it with the most sinister spin possible." Well, of course. He was posting on a North Carolina website, was he not? Go back among your own, he was instructed at such times. You want balance, you want nonpartisanship, join the League of Women Voters.

His polar opposite in sectarian terms (although equally possessed of intelligence, long memory, and the capacity for ripping new assholes in irksome posters) was the poster known as ManhattanHeel. She displayed a saucy, take-no-shit manner. One of the most visible and respected (and even feared) of the site's posters, Manhattan, or MH as she was often called, reminded me of James Carville and George Stephanopoulos, Bill Clinton's campaign team in 1992. Post an opinion about Duke, especially one that admitted even a speck of favor, and she arrived on the scene instantly with a definitive rebuttal, a one-woman quick-response team.

Here, for instance, is a post of Manhattan's occasioned by Donald Trump's visit to Cameron for the second Duke--North Carolina game of 2004. It serves as a fine example of the withering, take-no-prisoners tone Manhattan deployed against the Duke universe, or anyone who so much as sat cheering in a ringside seat at Cameron Indoor Stadium.

The only man I hate in America as much as K . . . is Donald Trump. So how fitting is it that he "just loves" Coach K? Let's see, Trump is egomaniacal, narcissistic, win-at-all-costs, an adulterer, a philanthropist for PR purposes only, and often a liar. He and K must have been twins separated at birth. The only difference is that Trump gets former Miss Universes and K gets Mickie.

Now, this is not just an uninformed rant. I have met Donald Trump. We share a degree from the same business school. I have a good friend who works directly for him (and no, a cheesy TV show was not involved in his employment). I have heard the untold stories, both business and personal. Basically, this is a man who would put his name on every roll of toilet paper in America if he could. You see the name TRUMP tackily plastered on as many buildings in NYC and Atlantic City as you see K's name blanketing every surface of Durham County. This is also a man who has repeatedly screwed bondholders out of hundreds of millions of dollars when a deal doesn't go his way. I'm sure he will be a star lecturer at the K Institute of Ethics.

So I ask you, is there anyone in America who is a better "face" for the K fan club than The (Other) Donald? Seriously, if I were a dook alum, I would be embarrassed to have yet another goon like him shilling for dook u. Just when I think it can't get any more ridiculous over at that faux gothic cesspool, it does.

I drank deeply from Manhattan's bottomless pool of vitriol. There was something tonic about it. On Inside Carolina, she was merely one among an entire nation of raging beasts, all as anonymous as members of the witness-protection program. And, oh reader, what a harsh world theirs was, full of fear and loathing. But at least that tiresome Carolina rectitude disappeared, replaced by an honest expression of dark, human passion that Nietzsche would have been proud to witness. Whenever the occasional wet blanket of a poster tried to plump for a little civility (there actually used to be a board member named PreacherJohn, or something like that), he or she was chased off.

That's because the Inside Carolina message board, unlike the state of Virginia, was not for lovers. It was for haters. All right, it was for lovers and haters. But the haters were the most enlivening. (The same was true, by the way, of Mike Hemmerich's Duke Basketball Report. When that site tried to be high-minded, as it occasionally did, it came off as too Olympian, even condescending. When it stooped to conquer, and let the nastiness rip, the DBR was enlivening, even for a Carolina fan.)

All of this suggested why ManhattanHeel was such a star. Her writing -- reliably tart, deeply invested in the subject, and suffused with a long, poisonous memory, especially in regard to all matters Duke -- charged the board with the vicious electricity of partisanship. Like American political culture these days, where being right or left meant never having to say you were sorry, sports websites thrived on polarity, especially when it was flamingly theatrical.

As a sassy gal in a guy's world, Manhattan attracted a lot of attention. My pulse raced a little faster whenever she landed on a thread. She was all that and she hated Duke. I decided I had to meet her -- for sociological reasons, of course. And so with the assistance of Ben Sherman, I made contact. Her real name was Sallie Beason.

Just from her posts, I had gleaned a little bit of her history. She'd lived for a while in New York while employed by some sort of financial services company; hence her board handle. But she had actually grown up down south and had returned home. She was married, and she lived in Charlotte, North Carolina's largest city, where she worked in real estate capital markets for the Bank of America. One Saturday, I went to see her.

We met for an early lunch on a Saturday morning so we could catch up later with her husband, Gary, and watch a game early that afternoon. The Mexican restaurant we had chosen was empty of customers. I asked her how much time she spent on Inside Carolina, and she told me she kept it open on her work computer "pretty much all day." "I just go over there, check it out, post a few things, and then go back to work." She grinned. "Multitasking." Before a waitress had even showed up to take our drink orders, we had trashed Dick Vitale. "He and all the commentators make Duke out like it's an Ivy League school, the way they handle their athletes," she said. "And we all know it's not. And the kids that are going to Duke, they're not North Carolinians. They get there and basketball becomes their social life. They're more impressed with what they think they contribute to the game as Krzyzewski's 'sixth man' than with what is actually happening on the court."

Her interactions with Duke graduates had only reinforced her perception of the school as a magnet for snobs-in-the-making. "I've just found all of them to be pretty smarmy," she said. "Maybe I'm guilty of a preconceived notion, but I'll give you an example. After finishing at Wharton, I went to Wall Street. I was working for what was then Paine Webber from 1997 to September of 2001. I'm a vice president of my group. We were always recruiting and interviewing associates, and once we got this kid whose father knew somebody. Someone came to my office, handed me a resume, and said, 'You need to interview this kid.' The first thing I see is that he was a Duke University grad. Honest to God, the first thing that ran through my head was that here are 30 minutes of my life that I'm never going to get back because I knew there was absolutely no chance I was going to hire a Duke kid. And I knew that before even meeting him. Now is that fair? No."

"True," I said. "But that's life."

"But then the kid comes in. And we actually got along pretty well. He had played soccer at Duke. And he was a smart kid. So it was going pretty well. And I actually said in my head, 'Oh, my God, this guy's pretty good'."

"That was really messing with your worldview."

"It was causing me a conflict," she said. "So we kept talking. And he wasn't from North Carolina. Shocker. He was from -- not New Jersey -- Virginia or somewhere. He said something about North Carolina. I said I actually grew up there. He said, 'Oh, did you go to school there?' I said, 'Yeah. I went to UNC.' He goes, 'I'm sorry.'"

"Uh-oh."

"I know he felt like he was trying to be funny. But I'm like, okay, dude . . ." "This interview is over."

"You're a kid interviewing with the vice president of a group and you insult her. Before I even met him, I knew I wasn't going to like him and guess what happened: He confirmed that."

The Duke basketball players struck her similarly -- as monsters of striving and entitlement. "I was at Carolina when Bobby Hurley was playing at Duke. I couldn't stand him. Those guys are always such media darlings, too."

"Like Wojo," I said. The name immediately sprang to mind. How could it not? Steve Wojciechowski stood in for every obnoxious, overachieving white point guard who ever played the game. In order to show the coach how psychotically into playing he was, Wojo was the kind of guy who ran to every huddle like Nutty Buddies were being handed out there by the Good Humor ice cream man. He was the sort of lead-footed guard who commentators like Dook Vitale were always saying made up for lack of native talent with hard work. Vitale and his media brethren shilled Wojciechowski right into being named National Defensive Player of the Year for 1998.

The truth was that Wojo played with such effort and intensity largely because he was so slow! It required vast expenditures of energy for him just to catch up to the play and the man he was guarding. Wojo slapped his defender around like a girl in a catfight. You bitch! After one mid-Nineties Carolina--Duke game, the North Carolina point guard Ed Cota displayed his scratched-up arms to the press and tried to explain Wojo's defensive prowess, saying something to the effect of "he fouls. A lot."

His style was so antithetical to physical grace that he made you think about inequalities of scale, of the fundamental unfairness of the universe when it came to the distribution of gifts, in this case physical talent. Worse, he made you wonder why white players tended to be perceived as hard workers and black players as naturally gifted. He made you see the lingering taints of race when all you wanted to do was watch a basketball game. None of this was exactly his fault, either. But his desperate, handslapping, knee-to-the-thigh scrappiness still rankled.

"I hated Wojo," she said. "And now," Beason said, "JJ Redick is starting to be that way. My husband called it. We were watching Duke play Georgia Tech. JJ hit a shot. He started talking so much shit. He was mouthing off while he was running backward. Gary's like, Holy shit, look at Redick talk. He's just like the rest of them. And you know what I say? It's like their birthright. They think that they've got Duke on their chests so they can act how they want. That comes from their coach.

"I don't know if this is like Carolina fans just being delusional, but I really think that our program is run very differently. I'll use as an example when Matt Doherty is in the huddle at Cameron and he makes a joke about the Duke cheerleaders being ugly. He apologizes publicly for that. Then you look at things that happen in K's program that are 80 times worse than that and it's like -- " She turned her palms upward and shrugged.

"In the end, it's the sanctimony," she said. "Trying to seem better than they are. That's the reason that Duke hate is nationwide now. It's not just Carolina fans. I guess the Dukies can say they're hated because they've won so much, but have they really won so much? In the ACC I can understand that view, but they have only one national championship since 1992. But the Dukies like that they're hated. It validates them."