The hits keep coming

The league has spent much of the soon-to-be-finished offseason dealing with the subject of head injuries and other disabilities suffered by current and former players. Medical professionals and other watchdogs have increased pressure on the NFL, arguing that the league does not do enough to protect its players.

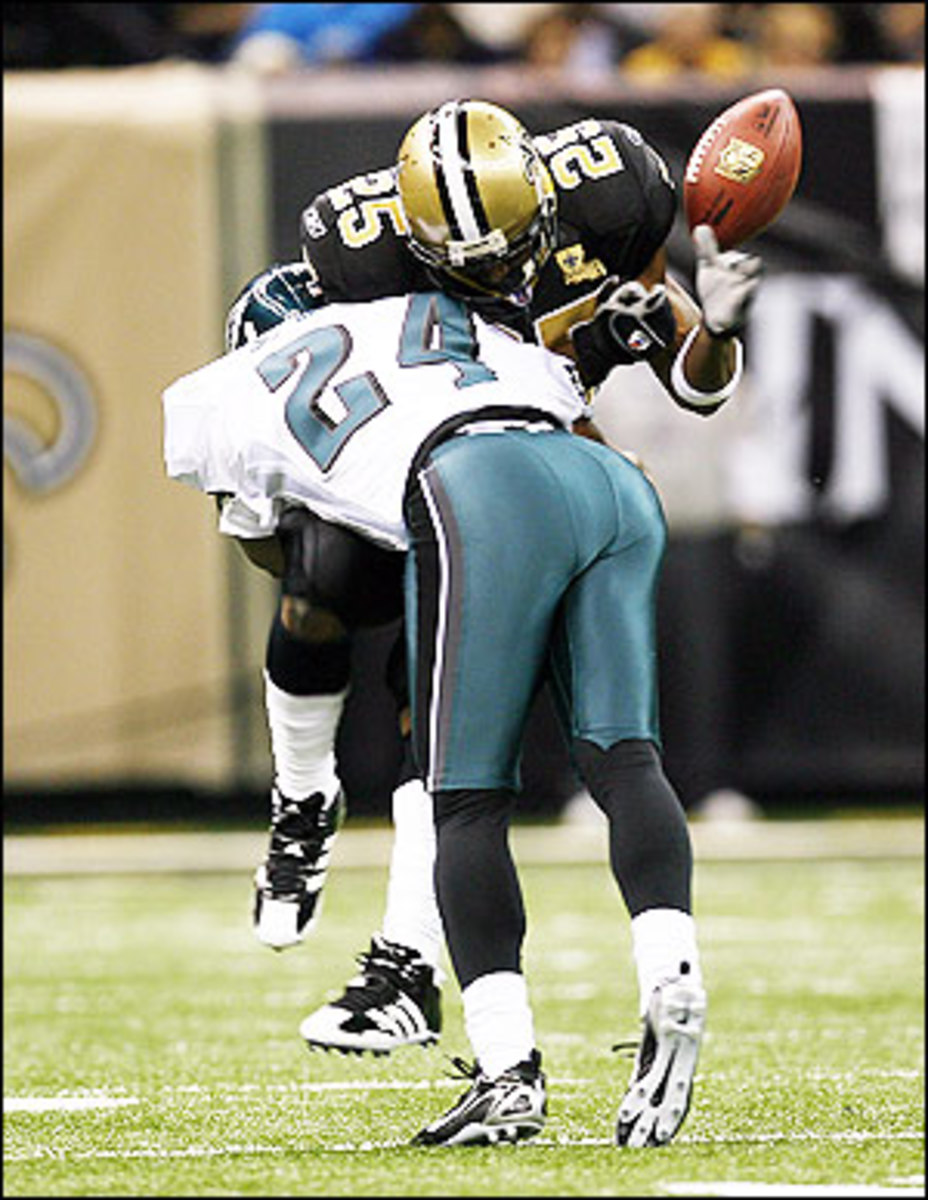

This came at the beginning of a story I wrote for SI.com that was posted in conjunction with a 6,500-word cover story that appeared in the July 30 issue of Sports Illustrated. The story examined the phenomenon of big hits in the NFL -- how they occur, what they feel like, why they are popular with fans and what lasting effects they leave.

I did not attempt to write yet another study of concussions on the modern football player, yet that topic influenced my work from day one (Players think about injury all the time; they bring up the topic). Nor did I try to write a rollicking ode to the big blow, yet that element made itself known as well (Players also savor the big hit more than you can imagine). I found what might have been a simple topic (collisions between players) to be, in fact, terribly complex on many levels.

Sunday's injury to Kevin Everett of the Bills only underscores that complexity. The news from Buffalo is a little different each day, and as of late Tuesday seemed to be markedly, even miraculously, better. From the grim prognosis of Monday, doctors are now saying that there is a chance to Everett might recover and live a normal life. Surely every player in the league breathed a sigh of relief.

Yet in Everett's story is a powerful reminder. Again, these are the words I wrote in July and I stand by them more than ever. "One conclusion is inescapable: Football is an almost indescribably violent activity, destined only to become more so. Even if one gives the NFL the benefit of the doubt and accepts that it has the health of its players foremost in its thinking, controlling the mayhem on the field is an almost impossible enterprise.''

Everett's special-teams hit on Domenik Hixon of the Broncos did not appear demonstrably more violent than 100 others like it in any NFL game. Yet after hitting Hixon's upper chest with his own helmet and shoulder, Everett fell motionless to the turf with an injury to his cervical spine.

This is not the time to preach loudly, but only to hope for the best for Everett. And there is a reminder: Every hit in an NFL game is violent and concussive. These are big, fast athletes delivering multiple massive blows on every snap. Fans and media and everyone who does not wear a helmet should be ever aware and ever respectful of what takes place on the field. This is not a video game. These are human beings.

There is little doubt that it is incumbent upon the NFL to enhance the safety of its players. That is easy enough to voice. Much emphasis has been placed on how a player is treated after he suffers a concussion. Players have claimed that they were forced into action before they were sufficiently recovered from a head injury. Deceased players -- Andre Waters, Justin Strzelczyk, Mike Webster -- have been diagnosed as having suffered from degenerative brain conditions before death.

To this end, the NFL has emphasized penalties and fines for helmet contact for more than a decade. This year the league has instituted a whistle-blower system to guard against players being pressured into playing while hurt. It also is requiring baseline neuropsychological testing before the season. These are sound and rational actions. Yet they seem woefully inadequate.

One by one, players I interviewed in May and June explained to me the force of their collisions and the zeal with which they deliver them. Big hits change games, change people. They are a necessary part of football. Seattle Seahawks' strong safety Brian Russell explained that NFL players spend 12 months a year in the weight room and in speed training, for the sole purpose of delivering -- or surviving -- ever more concussive hits.

I have written this before, but it is worth repeating. At the end of games, credentialed media are often permitted to stand on the sidelines at NFL games. From this perspective, the level of violence on the field is stunning. Every diehard NFL fan who watches the league solely on a plasma screen from the comfort of his or her couch should experience this effect. The game is jaw-droppingly wild, the collisions louder than you can imagine. Even the brilliance of NFL Films does not do it justice.

I bring this up to make a point: The way NFL football is played, people are going to get injured, sometimes badly. Players are frightening athletic specimens, whether through natural means or otherwise. They are fast, strong and motivated. Read my SI story to understand the emotional fervor with which they perform their job (and the pain they feel afterward).

It is common to describe the cartoon violence of the 1950s and '60s NFL as far beyond that which is experienced today. It's true that players from that era employed more creative means to maim each other: The leg whip, the clothesline and the lower-body crackback. Helmets were still legally engaged as weapons. Rules changes have made the game more civilized.

But the athleticism of the modern player more than offsets the tamer boundaries. Current-day defensive ends are faster than 1950s defensive backs. Modern-day defensive backs are bigger than some 1950s linemen. Now we have weight rooms, sprint coaches and supplements.

What's more, the game is now a lottery of sorts. Salaries are astronomical, but careers remain short for most players. There is intense pressure to maximize physical skills and intimidation. The marginal player will be cut loose for delivering anything less. The standout player will be paid less than he desires. The bottom line is production, and for nearly every player on the field, production is tied to either punishing somebody or getting punished and playing on.

Is there any way to change this? I doubt it, and furthermore, who would want to? The NFL and even major college football are spectacularly successful businesses. Michael Vick's troubles are being described as a crisis for the league, but regardless of whether Vick ever plays in the NFL or not, the league will roll over this controversy like it's a small speed bump.

Violence is essential to football, both as a competitive and economic factor. The NFL and the many watchdogs who have pressured the league are to be commended for trying to protect players' health, both long- and short-term.

But in the end, the game lives by the collision. Unless that changes someday, bodies (and minds) will be subjected to ever greater punishment. That is the cost of doing business.