Daring under duress

One summer, maybe 20 years ago, I was vacationing with my family, and on one particular lazy afternoon I was sitting around outside the cottage we were renting, watching some ants. They were engaged in the project of dragging the body of a beetle back to their nest or wherever they lived.

It was like a military precision operation. Some dragged it until they got tired, then they gave way and others took over, while still others scouted the terrain ahead. This would certainly be a fine feast for their colony. It was beautifully organized.

I don't know what devil possessed me to do it, but all of a sudden I lifted the beetle from their midst. They went nuts, poor little things, running about in disarray, bumping into each other, tracking, backtracking, wandering off in confusion. I felt bad about it and restored the beetle to its rightful place, but it took them about two minutes before they settled down and resumed their duties.

Many of them never got over it and suffered lingering psychiatric problems. Some were profoundly affected by the experience, claiming they had personally seen the Hand of God. They became deeply religious. As for me, I recalled the whole scene Sunday night when I watched the Colts lose to the Chargers.

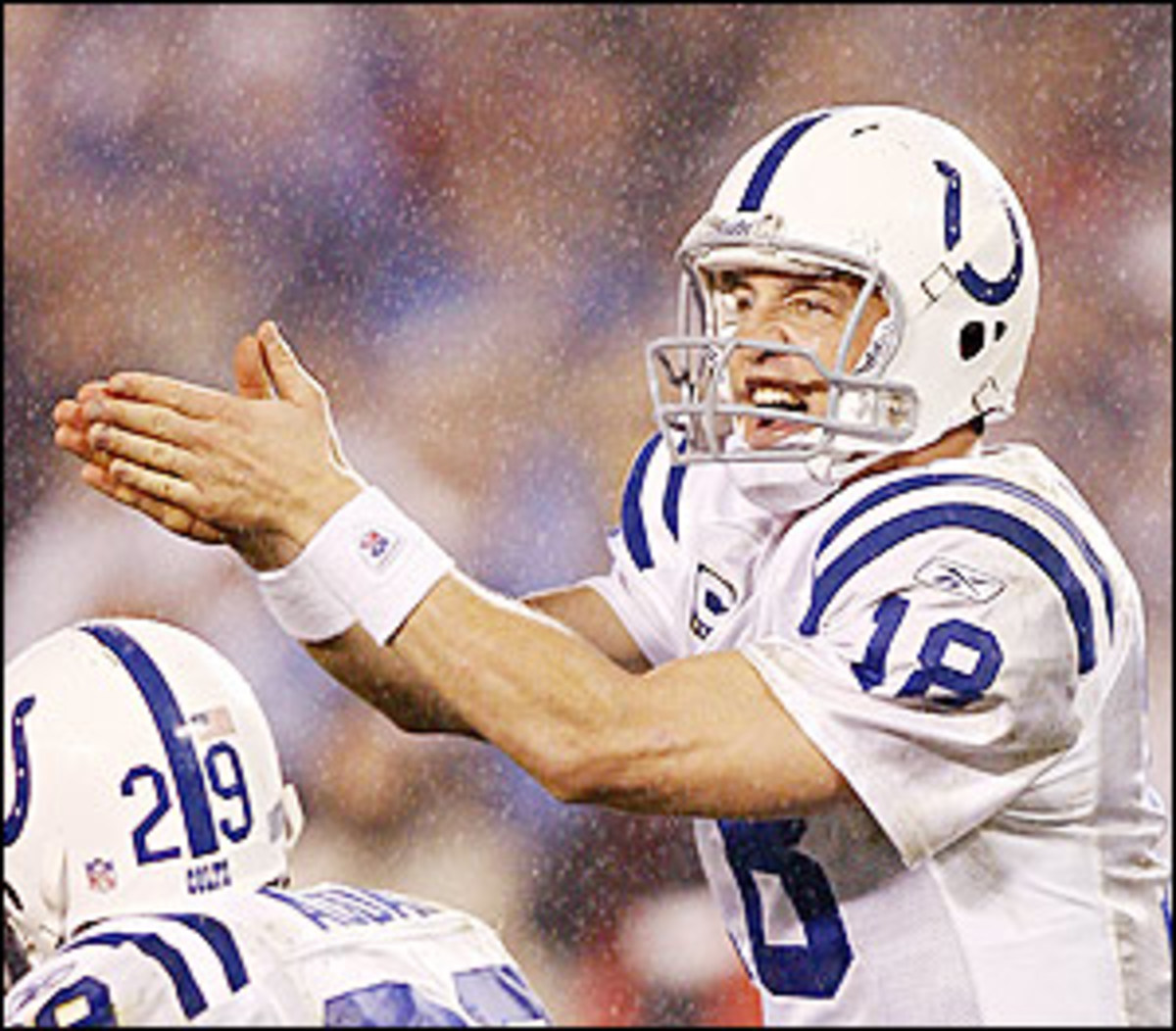

Peyton Manning, when he has his full colony of workers, is the closest thing to a drillmaster you will see on a football field. The operation is meticulously organized. But start removing elements from it and the drill can break down. And take away as many key portions of it as were removed Sunday night and you get, well, six interceptions.

The Colts went into the San Diego game with only 17 offensive players in uniform. Two went down during the game. Two key receivers, Marvin Harrison and Dallas Clark, were missing. Their top draft choice, AnthonyGonzalez, who was supposed to be in the mix somewhere, also was out of action. They were left with Reggie Wayne and back-ups, including a street free agent activated in October named Craphonso Thorpe.

They fell behind, 23-0. I thought the result would be like one of those New England Patriot adding machine things, except that Norv Turner doesn't run up scores. Then the beetle was returned and remarkably, things settled into some form of normalcy. And even with strange numbers on the uniforms of Manning's receivers, the Colts drove when they had to, scored, put points on the board, brought it back to 23-21 and took it down to the shadow of the Chargers' goal, where a missed 29-yard field goal did them in.

It was an amazing example of battlefield command, of somehow mustering a shattered army. But that's what Peyton is so good at, fighting the odds. I've seen him take some ferocious beatings, while running his show. For some reason teams that are hesitant to blitz other quarterbacks seem to feel it's the best strategy against him. I saw the Ravens, two years in a row, throw all sorts of exotic pressure packages at him, but he hung in -- it seemed as if almost every pass he threw was off his back foot -- and by the third quarter he had worn them out.

Some of the greatest games I've seen him have were under the most severe duress, and maybe his numbers weren't the best those times, but the memories he left were the most lingering. And looking back on the great quarterback performances that come to mind, the ones that are most indelibly etched are the ones that involved the most severe conditions.

A quarterback who stands tall in the pocket, facing a minimal rush, throwing to an all star cast of receivers is a pretty picture, but there's nothing about it that reaches me on an emotional level. But the guy who somehow manages to pull one out when the weather is bad and his offense is banged up and the other team is smelling blood -- well, that's what it's all about, I feel.

Bill Walsh used to run an exercise for his quarterbacks called the bad situation drill, which called for them to throw passes under all manner of discomfort. It seemed like a helter skelter type of thing, but every situation was carefully rehearsed. Joe Montana credited it for the play that beat Dallas on the way to the Niners' first Super Bowl, running to his right and just before going of bounds, lofting one to Dwight Clark for the winning score. But I never saw him put it to better use than in a game I covered in Philly in 1989.

Buddy Ryan sacrificed all principles of sound coverage to bring a monster blitz package at Montana. The night before he told me, "If he finishes the game, then I haven't done my job."

Well, Montana finished it -- just barely -- but it was close. The Eagles sacked him eight times and sent him to the sidelines twice. But what they paid for in unsound coverage produced 38 points and 428 yards and five TDs for Montana -- and a 10-point 49ers victory. Watching that game was like watching a morality play, good against evil, with both sides taking some serious hits.

A lot of the greatest performances I've watched didn't involve winning at all, and those yahoos who put some resonance into their voices and proclaim, "Without the victory, it doesn't mean a thing," don't really understand that a certain nobility can also accompany hopeless causes.

The finest game I ever saw John Elway have was in his junior year at Stanford. They were badly outmanned against Purdue, which seemed to get rushers in on him on every play. That was the first time I saw the miracles Elway could work on the dead run, the depth and accuracy he could get on his throws while he was in full flight. Stanford lost, but Elway put a scare into the Boilers. I don't remember how many yards he threw for ... over 400, I'm sure ... but I do remember seeing the Purdue players lining up to shake his hand after it was over.

Once I ran into Fran Tarkenton when I was covering a playoff game, after he had retired. We were talking about his career with the Giants and some of the goofy stuff that happened there. I told him that he might think I was nuts, but the best game I ever saw him have was against the Cowboys in 1971.

Dallas would go on to be the Super Bowl champ that year. It was one of the greatest Cowboys teams in history, Roger Staubach and Duane Thomas and the Doomsday Defense at its toughest. The Giants were tied for the worst team in the NFC at 4-10. The runners Tarkenton had in his backfield that Monday night in Dallas were Bobby Duhon and Junior Coffey. His receivers were Clifton McNeil, Rich Houston and Don Herrmann from Waynesburg State. And yet this ragtag outfit took the Cowboys down to the wire, and the reason was Tarkenton. He ran, he threw on the move, he bought first downs through sheer force of will. Dallas ended up winning by seven. They should have won by 30.

So I told Tarkenton that was the best game I ever saw him play, and he nodded and said, "You know something? It's my favorite, too."

Well, I don't think that someday Peyton Manning, if he's sitting around with some old sportswriter, will classify that six interception night as one of his best. I wouldn't, either. It belongs in a different category, a different type of greatness, the ability to organize any group he ever finds himself on the field with into a striking force that at least can bring a tough game a heartbeat away from victory.

I'm sure it was one he'd like to forget. But for people such as me, with long memories, it was very special.