With political involvement afoot, prepare for major BCS change

Before you contemplate United States of America vs. the Bowl Championship Series, imagine for a moment that only 11 American companies produce ice cream. Six of the companies earn the bulk of the revenue -- either because they've been around the longest, because they gobbled up the most lucrative mom-and-pop shops or because they simply make the best product. Five other companies also produce ice cream. On occasion, a subsidiary of the smaller five produces some of the nation's best ice cream. Sometimes, the six big companies contract with the five to produce ice cream for lucrative, one-off events, but most of the time, the companies keep to themselves.

Now imagine the six richest companies got together and decided to fix the price of ice cream. In return, they would split the revenue from the January sales of ice cream evenly. The other five would be welcome to join the consortium, but they would have to take a significantly smaller percentage of the revenue. If they didn't join, they'd simply be squeezed out of the ice cream business. Join, the big boys would say, or you may as well drop down to the Italian ice subdivision. Oh, and by the way, in this example, all 120 subsidiaries of the 11 ice cream companies receive millions in state and/or federal funding.

If that ever happened, the federal government would bust the ice cream cartel using the Sherman Antitrust Act, a law passed in 1890 to keep companies from erecting unreasonable barriers to competition. At the turn of the 20th Century, President William Howard Taft used the Sherman Act against Standard Oil and the American Tobacco Company. In 1982, American Telephone and Telegraph -- better known as "the phone company" -- fell to the Sherman Act and its younger brother, the Clayton Act.

If the letter Sen. Orrin Hatch (R-Utah) received Friday from the Justice Department is any indication, get ready to watch the worst fears of the BCS overlords come true. Then get ready for some form of a college football playoff -- because that's where this is headed. When the dust settles, power conference commissioners either will compromise to preserve their partnership with their bowl cronies, or the BCS will cease to exist.

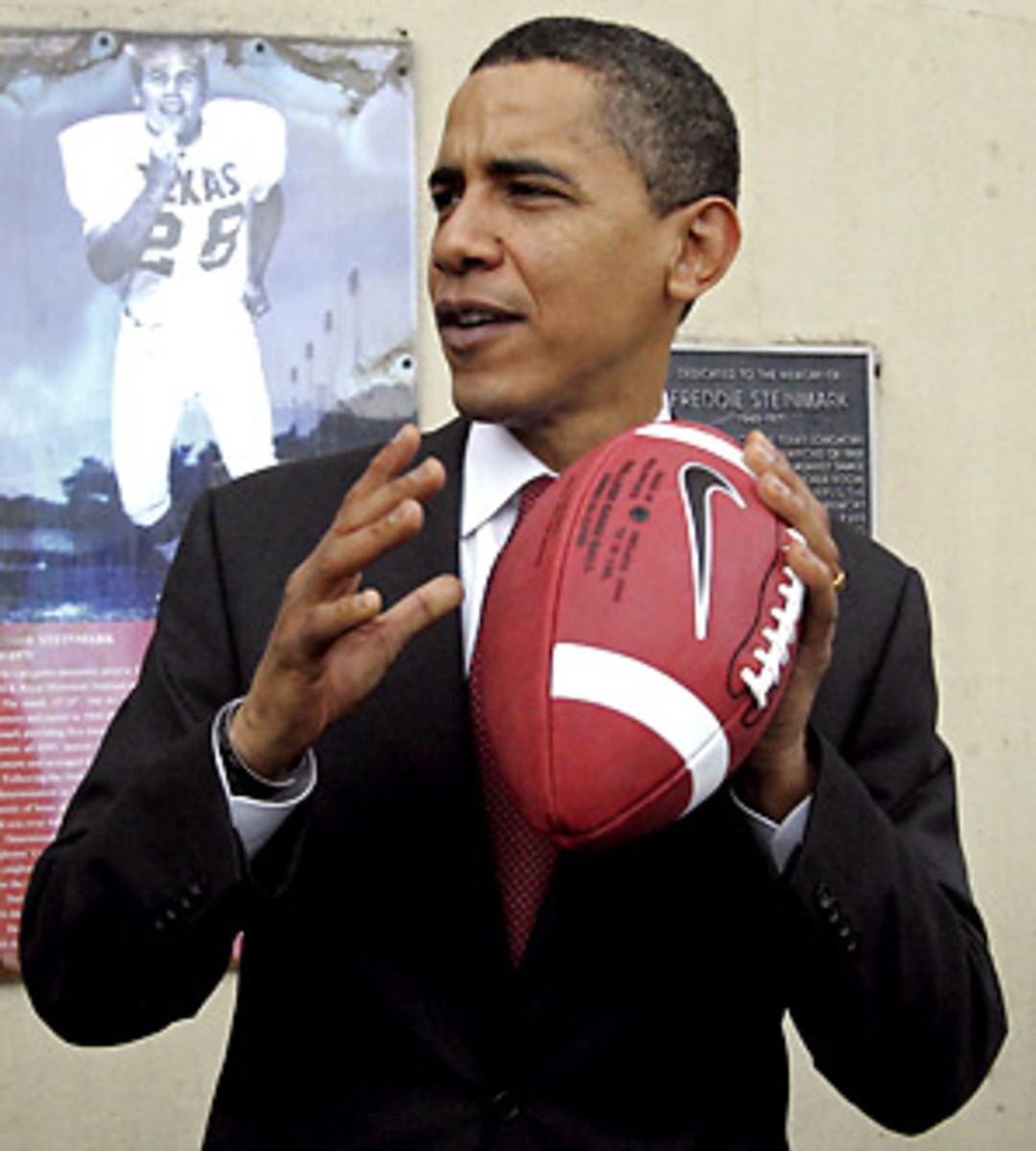

According to the letter, the Justice Department (the rock) may launch an investigation to determine whether the BCS violates antitrust laws. Meanwhile the Obama administration (the hard place) is willing to explore several options, including encouraging the NCAA -- which runs 16-team playoffs in three other football divisions -- to take over the postseason, asking the Federal Trade Commission to examine the BCS and pushing legislation that could "target universities' tax-exempt status if a playoff system is not implemented."

The leaders of the BCS could sit in their hollowed-out volcano and chuckle after U.S. Rep. Joe Barton (R-Texas) hauled them before a House subcommittee last year. They could lampoon Barton's bill, a relatively meaningless exercise in semantics that would ban the BCS from advertising its No. 1 vs. No. 2 game as a championship.

They can't laugh now, but they can duck.

Predictably, BCS executive director/mouthpiece Bill Hancock released a statement Friday reiterating the BCS defense whenever antitrust/cartel questions are raised: Hey, look over there!

"This letter is nothing new and if the Justice Department thought there was a case to be made, they likely would have made it already," Hancock's statement read. "There is much less to this letter than meets the eye. The White House knows that with all the serious issues facing the country, the last thing they should do is increase the deficit by spending money to investigate how the college football playoffs are played."

First, it is something new, and BCS leaders know it. They hired former White House press secretary Ari Fleischer for a reason, and it wasn't because they enjoyed watching his work on CNN in the early days of the Bush 43 administration. So far, Fleischer and his minions have served only to enrage fans further by creating a Facebook page and a Twitter feed that severely underestimate the customers' intelligence. Now, they're going to earn their money. The BCS hired Fleischer because he can navigate the halls of power in Washington, not because he makes a mean Facebook page.

Second, the federal deficit will not rise one penny if the Justice Department investigates the BCS. The Justice Department employs people, and those people must do something. If they are ordered to investigate the BCS, there is an opportunity cost exacted -- they could have investigated something else -- but not a monetary one. Also, it is the government's responsibility to monitor the activities of a multi-billion business that involves more than 100 publicly funded universities.

Third, Hancock's response doesn't actually answer the question; it simply misdirects. So, as a public service for Hancock and the bowl lovers everywhere, I called Michael McCann, the Vermont Law School professor who writes about legal issues for SI.com, and asked him to explain how the BCS might defend itself against an antitrust challenge.

"The people that support the BCS would say that we wouldn't have a national championship without it," McCann said. "All it does is reflect the college football standings. It doesn't do anything other than that."

McCann also summarized what the Justice Department might argue in an antitrust proceeding against the BCS. "It's arguably a cartel," McCann said. "It's producers and sellers joining together to control a product's production, price and distribution. ... In terms of anticompetitive effect, it affects prices. It also creates financial and recruiting disadvantages for some schools. There are economic disparities between BCS members and non-BCS members. All of that would go into an antitrust analysis."

In a courtroom, McCann said, neither side would be a four-touchdown favorite. "I don't think it's a slam dunk either way," he said.

Unfortunately for the BCS, the pro-playoff crowd has a powerful and motivated advocate: a president under fire who desperately needs a politically popular win. If this pressure results in the creation of a playoff, we probably should thank the voters of Massachusetts for electing Scott Brown last month. That win for the Republicans added one more thorn in the side of Obama, who is getting ripped on both sides of the aisle on major issues such as health care and the war in Afghanistan. By pushing the BCS to disband or to institute a playoff, Obama can claim a victory that will make Republicans and Democrats happy. It's a small victory, to be sure, but a victory nonetheless.

BCS leaders have always threatened that if the government got involved, they would simply dissolve the cartel and go back to the old bowl system. That may not be feasible. The old system would be fantastic for the SEC and the Big Ten, which would be wooed by all the major bowls. It probably would be a disaster for the Big East, which, in recent years, has looked like the gawky kid picked last for kickball every time the BCS bowls choose their participants.

It's no stretch to assume that if the BCS dissolved itself, the major bowls would leave the Big East out of any new deals. That would leave the Big East with the Champs Sports Bowl, the new-for-2010 Yankee Bowl and the Meineke Car Care Bowl as its best partners. None of those bowls is going to replace the $17.7 million the Big East received from the BCS. So if the Football Bowl Subdivision membership voted on whether it wanted a full-scale playoff (big money for everyone) or a bowl-based system (big money for the SEC, Big Ten, Big 12, Pac-10 and maybe the ACC), the Big East schools would have to seriously consider standing with the Mountain West, WAC and the rest.

Besides, even BCS leaders will admit that there's more money in a playoff. The NCAA basketball tournament brings in an estimated $545 million a year, and college football is exponentially more popular than college basketball. The BCS brings in only $150 million a year, but it funnels most of it to the most powerful conferences. Government intervention would strip those conferences of their power. After that, given a choice between less money and more money, here's betting college presidents forget about their arguments against a playoff and opt for more money.

There is another solution, and it probably will work. Compromise. Offer a plus-one -- a four-team, bracketed playoff -- and offer to split the revenue 11 ways. Then the president could declare victory, and the relationship with the most powerful bowls would be preserved. That could very well result in what Hancock calls "bracket creep," but one man's creep is another man's market correction.

BCS leaders may have to take that chance, because they may have no other way to salvage their way of doing business. Hancock spent part of his State of the BCS address on Jan. 7 bragging about the unprecedented access and revenue the six power conferences have bestowed upon their five little brothers. He failed to mention the timeline. The BCS increased access for the leagues without an automatic berth at its meeting in April 2006. Not coincidentally, Barton had hauled BCS leaders before Congress five months earlier.

Expect even more cooperation this time, because in the president and the Justice Department, the BCS has run into a pair of enemies it can't defeat.