Cooperstown still a little slice of heaven for fans, baseball legends

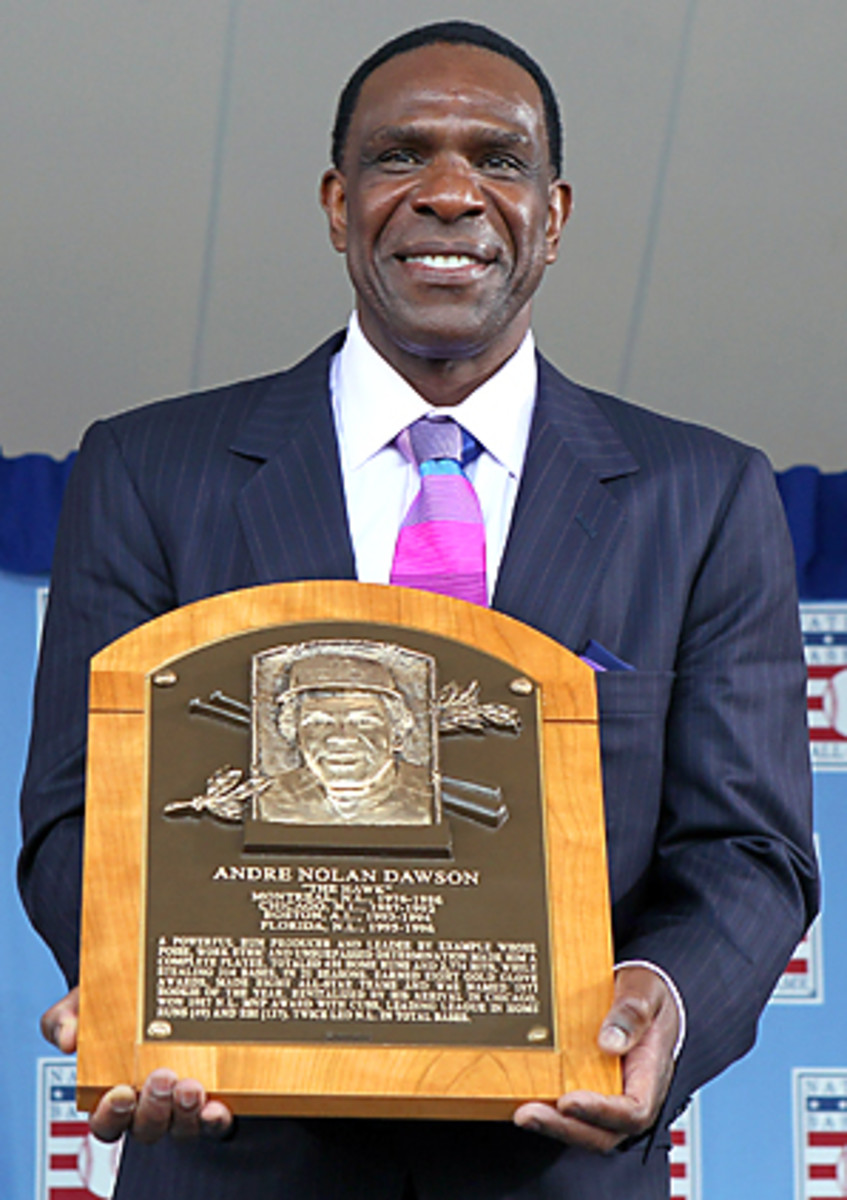

It seems impossibly far from the reality that is Major League Baseball today -- from, say, Yankee Stadium, 185 miles southeast of here, where on Sunday a man who will make $33 million this season and who has admitted to using performance-enhancing drugs tried again to hit his 600th home run in front of his well-heeled fans, some of whom paid more than $1,000 for a ticket to watch him try, while gobbling all-you-can-eat shellfish and steak. The people who put on Sunday's ceremony in which Expos and Cubs slugger Andre Dawson, Cardinals manager Whitey Herzog and umpire Doug Harvey were inducted into the Hall of Fame, and the 10,000 or so people who came to watch it, like to maintain that distance, as best as they can.

This is a place where people happily nod along to the old-timey baseball anthems that are played over the loudspeaker -- a cloying ukulele version of "Take Me Out to the Ballgame"; a ditty by someone named Terry Cashman that includes such lyrics as, "Sunny days and Willie Mays / You'll be glad you took the trip / To Cooperstown, the town where baseball lives." It's a place to which the ceremony's opening speaker can without irony greet those in attendance with the words, "Welcome to Cooperstown, America's most perfect village." It's a place where grown men can wear every piece of baseball paraphernalia they own, no matter how ridiculous -- gentleman in the San Diego Padres-themed Hawaiian shirt, you know who you are -- and feel sartorially at home.

It's a place where the use of the word "great" far exceeds that of any other adjective. It's a place where every person is special, even if emcee George Grande has some trouble explaining exactly why that is true for everyone (on Sparky Anderson: "A manager and a man," undoubtedly good news to his wife; on Don Sutton: "Did his best every day"), and even if Grande has some trouble nimbly segueing between all the specialness ("Harmon Killebrew, Killer, is the pride of Payette, Idaho; and the next gentleman is simply the Dominican Dandy, Juan Marichal!")

It is a place devoted mostly to an idealized vision of baseball, though reality did break through at times on Sunday. Jon Miller, the broadcaster who was honored as this year's winner of the Ford C. Frick award, strangely included both his accountant and his lawyer among the people he thanked in his speech. Commissioner Bud Selig was booed rather passionately whenever his name was announced (one must be very unpopular indeed to be booed here). A group of erstwhile Montreal Expos fans, who had assembled to celebrate Dawson's enshrinement, chanted Let's Go Ex-pos again and again, as if to remind everyone of the extinction of their once beloved team. Dawson himself mentioned his friendship with He Who Shall Not Be Named (within the village limits of Cooperstown) -- Pete Rose -- and made some oblique references to "mistakes" that have recently been made in baseball by "individuals who have chosen the wrong road," mistakes that have led to "a stain on the game, a stain gradually being removed."

But still: Sunday's ceremony amounted to a rather pleasant three-hour exercise in mythmaking. The class inducted here was not among the Hall's most singularly impressive, consisting, as it did, of one player, Dawson, who finally made it in after falling short in his first eight years on the ballot and who everyone kept saying would have been really great had he had better knees; a manager, Herzog, who ranks a not-bad 32nd on the all-times wins list; and an umpire, Harvey, who knew and applied the game's rules rather well and over a long period of time. But each, as far as we know, is a man of integrity, and that in addition to their more-than-solid (if not utterly outstanding) accomplishments on the field is enough to make them immortals here in baseball's Brigadoon. "Being elected to the National Baseball Hall of Fame in Cooperstown, New York is like going to heaven before you die," said a tearful Herzog.

Over the next few years, this particular heaven's gatekeepers are going to have to decide how to deal with figures like Barry Bonds, Roger Clemens, Rafael Palmeiro, Sammy Sosa, and, eventually, Alex Rodriguez, and they won't be able to treat all of them in the way they've treated Mark McGwire, which is, essentially, to pretend that he does not exist. On Sunday, it was clear that everyone in Cooperstown was more than happy to push such considerations aside, and to do so for as long as is possible. This was a day to embrace a version of baseball that has little to do with money, and nothing to do with drugs, and everything to do with great people who play a great game for only the greatest of reasons. A version of baseball in which it's absolutely true, as Dawson said again and again, that "if you love this game, the game will love you back." Here in the remote, strange village that is Cooperstown -- understood, after all, as the sport's birthplace, even though it almost surely is not -- you could almost believe in all of that.