Williams has built winners with unique approach on South Side

The Second City's second team plays, physically, at the fringe of respectable Chicago, that renowned center of molecular gastronomy, Mies van der Rohe structures and futures trading. Home plate at U.S. Cellular Field is a brief walk from the old Union Stock Yard Gate, two L stops from the second most crime-ridden corner in the United States and an hour's bicycle ride from depressed reaches of northwest Indiana which manage to be gray and brown even on perfect June days. The Cubs play in the town of departing mayor Richard Daley's idylls, full of wrought iron fencing and green markets. The White Sox don't.

"We may as well be in two different cities," says Kenny Williams, the team's general manager. "It's that different. So draw a line down through Madison Street or whatever the dividing line is, just like North Dakota, South Dakota -- north Chicago, south Chicago, just call it different states."

To understand why Williams is so good at what he does, this is where you start, with an awareness that he operates not in a large market, but on the South Side, which is usually called "working class" but could more accurately be called "broke". Consider that by one measure, which multiplies local population by average income, the size of the Chicago market is closest to the major league average, and that the Cubs draw the moneyed class, and you'll see the difficulties of the situation.

Despite playing in the third largest city in the country, the Sox rank 17th in average attendance per game among the 30 major league teams this year. According to a recent Harris poll, they rank 15th in popularity. Running the club is an exercise in suffering such big city annoyances as a large, obnoxious press corps without such compensatory benefits as having quite enough cash to buy division titles outright. (The Sox run decent payrolls, but are closer in spending to the Houston Astros than the Detroit Tigers this year, and ranked 12th in baseball last year.)

Judged as the record of a team situated in an alpha world city, the Sox's run since Williams' ascension to his present job in November 2000 -- the 10th-best record in the major leagues, no truly bad seasons, two playoff appearances and a World Series championship -- isn't at all bad. Taken as the record of a team in a relatively modest market, it's very good.

There are two key reasons why the Sox do well. The first is that they understand probability. While Williams would protest that the team's goal every year is to win the World Series and that anything else is a failure, in truth they're annually built to win 85 to 90 games, with the understanding that with some good fortune they might win 95 and a pennant, and that with a few injuries or off years they might slip below .500. A dodgy plan in a given year, building a decent team every year is a sure way to eventually come up with a great one.

The second is that they want to win, which is not always a given. When things are breaking their way, they become ruthless -- turning over the closer role to untested waiver claim Bobby Jenks in 2005, handing a top setup role to June draftee Chris Sale this year. Asked why he was willing to take on millions of dollars in salary obligations to add Manny Ramirez this August, owner Jerry Reinsdorf said, "When you have a year where you think you have a chance to win, you have to try. It's as simple as that."

All of which explains why taking on Ramirez was the perfect expression of a sound team philosophy, and why scoffing at the Sox for the way a close race with the Minnesota Twins has turned into a joke the past few days as Manny has flailed misses the point. Without the willingness to take a well-timed risk, the Sox would never have been in the race at all.

The White Sox have a slightly unusual culture. From Williams to manager Ozzie Guillen to team chef Roy Rivas, the team is run and staffed largely by people who have worked for Reinsdorf for decades. As often happens in such cases, the ministers have adopted some of the czar's tics, in this case a knack for saying things that aren't quite as banal as they sound. Take Williams' explanation of what he looks for in a player.

"We have to have players that are Chicago tough," he says. "This is a little different than other places, because you very rarely get a player that's going to come here and everyone is jubilant and all for it. That player generally -- particularly with most of my acquisitions -- comes with a certain amount of negativity attached, of skepticism attached. So if that particular player hasn't already dealt with a certain adversity in his career or in his life and bounced back from it and remained strong from it, he isn't going to survive."

Baseball types talk a lot about adversity. In theory, no one wants players who yield to it, and everyone wants players who triumph over it. In practice, nearly all of them want players who have never had to deal with failure at all. There is a reason why Derek Jeter is considered the ideal player.

Williams is different; his claim that he wants players who have dealt with a certain adversity is demonstrably true. This year's key Sox include formerly busted prospects John Danks, Gavin Floyd and Carlos Quentin; Alex Rios, a player so lost the Toronto Blue Jays were willing to literally give him away last year just to be rid of his salary, and Alexei Ramirez, a Cuban native.

Even in his more minor dealings over the past year, Williams has tended toward failures. Short reliever J.J. Putz was signed coming off an arm injury; left fielder Juan Pierre was another player his team was willing to pay to be rid of; infielder Omar Vizquel is 79 years old. All have contributed. Putz set a team record for most consecutive scoreless appearances, Pierre has brought enough speed and defense to be passable despite a .313 slugging average, and Vizquel has orchestrated a surprisingly tight infield defense and run up the second best on-base average on the team.

If, instead of talking about adversity and toughness, Williams were to start speaking in business jargon, the broad baseball-loving public might credit him more for his ability to identify undervalued assets. Of course he's had his failures; young pitchers Gio Gonzalez, Daniel Hudson and Clayton Richard and outfielder Nick Swisher are wearing the uniforms of other teams and demonstrating quite convincingly that Williams' eye for the undervalued asset doesn't always extend to his own roster. And his refusal to sign designated hitter Jim Thome for a fairly nominal sum this past winter is probably the single biggest reason the Sox's pennant hopes were ended this week -- the team spent most of the year getting utterly intolerable hitting from such Thome replacements as Mark Kotsay while the big man was slugging above .600 for Minnesota.

Anyone with a decade as a general manager will have made his mistakes, though, and Williams' aren't nearly as consequential as his successes. What's perhaps most impressive about his ability to extract value from failed prospects and young veterans who have seemingly lost their way is that the way he does so is unique to the Sox.

Take the pitchers. The Sox are famously durable: During coach Don Cooper's tenure, the team has had half again as many 200-inning seasons from their starters as the next best team, and they've averaged just 17 starts per year from pitchers outside. Better is that they're flat good. This year, for example, they're tied for the lowest home run rate in the American League, even though U.S. Cellular is perhaps the best home run park in the circuit.

None of this is accidental. The Sox focus on motion and efficiency, throwing a lot more cut fastballs than the average, and many fewer arm-torquing curveballs. Pitchers such as Danks and Floyd consistently start walking fewer batters on their arrival in the majors, and surrender fewer fly balls. Even when they do, the motion on their pitches helps them -- by one calculation, the Sox have picked up several wins' worth of runs just by giving up fewer home runs than would be predicted by their fly ball rate.

Edwin Jackson, acquired in the Hudson trade in July, provides a perfect example: A trade to the Sox turned him into a new pitcher. He dropped his curve, started throwing his cutting slider more often, cut his walk rate in half, and picked up an extra two-thirds of an inning per start. His ERA fell by more than two runs.

This is a program, you'll note, almost perfectly suited to pitchers who have struggled with the above-mentioned adversity. Give Cooper a big man with a moving fastball and a decent motion and he can get good pitching out of him by tweaking his mechanics, teaching him a new pitch, coaxing him to throw strikes. Williams' ability to identify such pitchers and pick them up at (usually) cheap rates offers him an immense advantage over other teams. He has an alchemist working for him.

Should Williams get the credit for that, or for a medical crew that's helped keep the team unusually healthy even when fielding the injury-prone and/or aging likes of Quentin, Thome and Paul Konerko? It's hard to see why not. Building and retaining a good staff is the better part of being a general manager. If Williams has set up a system that allows him to get more out of certain kinds of players than anyone else can -- if the otherwise infirm can take the field for him, while wild pitchers harness their fastballs and the mildly eccentric feel free to do their thing under the tolerant Guillen -- and if he can reliably obtain those kinds of players, he's up on all but the very elite among his peers.

Williams has real weaknesses. His unwillingness to pay up for real power hitting, his habit of dispersing money among a lot of so-so role players rather than focusing it on one really good one, his (until recently puzzling) drafts, and his constant mad pursuit of such great catches as Ramirez and Jake Peavy have all cost the team. These are, though, all correctable. And if he continues to grow and evolve, the Sox should be in for a decade even better than their last.

Most of the core players here -- Danks, Floyd, Rios, Quentin, Ramirez, second baseman Gordon Beckham -- are still in their primes. The Sox have tens of millions of dollars in salary obligations coming off the books this winter, and will have even more to spend if Peavy, realistically the No. 5 starter despite being the best paid member of the team, proves unable to come back from unprecedented surgery to repair a side muscle that rolled up like a windowshade this summer.

This year, the dice didn't come up for Williams and the Sox. They built their 85-to-90 win team, picked up the best available player to fill their greatest need when it looked like they were close, and their numbers just didn't come up. Next year they'll likely be just as good, and if Williams is shrewd with his spending they could easily enter the year as a pennant favorite. You can see failure, if you care to, in Flushing, Queens, or on the North Side of Chicago. This isn't it.

1. Claimed Manny Ramirez on waivers

Ramirez may not have an extra-base hit as a Sox, but adding one of the game's best hitters for nothing but money when they were still in the race was absolutely the right move.

2. Signed J.J. Putz

Putz, coming off an injury, has been a key part of a very effective bullpen.

3. Signed Andruw Jones

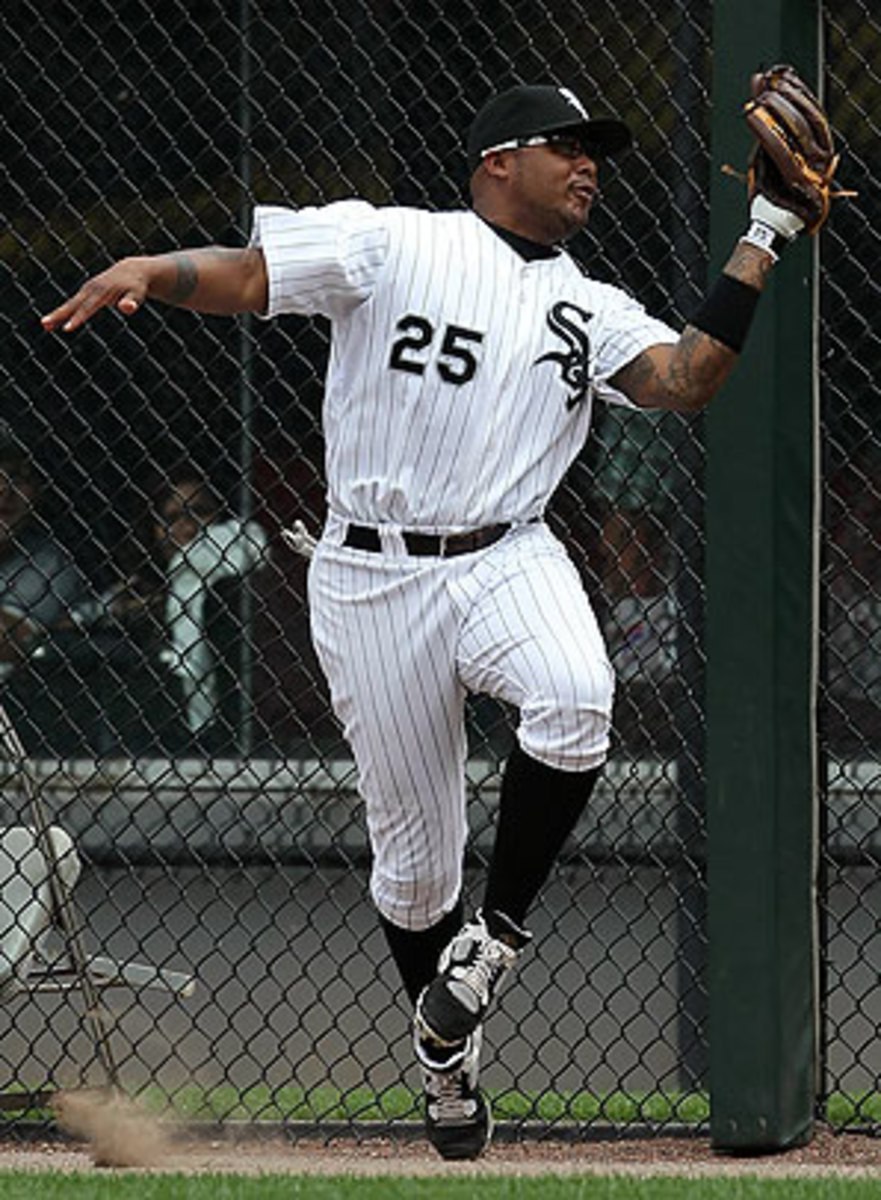

Jones has been quite useful as a role player, slugging nearly .500 and batting .467 in September for his best campaign in four years.

4. Signed Omar Vizquel

Centuries after his birth, Vizquel remains a capable reserve. His getting into a game as a designated hitter was a highlight of the year in baseball.

5. Traded Jon Ely and Jon Link to Dodgers for Juan Pierre and money

Roundly mocked, the decision to fill a hole in left field with Pierre, who can't hit, has turned out decently well. He's cheap and does things that aren't hitting well enough to deserve his playing time.

6. Traded Josh Fields and Chris Getz to Royals for Mark Teahen

Moving two bad players for a slightly below average one at a position of need was no masterstroke, but wasn't much worth criticizing. Signing him to an inexplicable three-year extension was.

7. Traded Daniel Hudson and David Holmberg to Diamondbacks for Edwin Jackson

With Hudson (1.67 ERA) looking every bit the stud starter his minor league numbers suggested, this deal looks pretty bad right now despite Jackson's superb performance with the Sox.