Dream matchup gets a sequel as Halladay faces Lincecum in Game 5

Each player speaks a bit softer, for volume is the privilege of the victorious. Fewer players make themselves available for interviews. Television microphones are shoved inches closer to the players' lips, and writers slouch forward so that their quote transcriptions are accurate.

The Phillies' clubhouse is notoriously scarce after losses -- except noticeably less so after Game 4's heartbreaking 6-5 loss to the Giants, putting Philadelphia on the brink of elimination as it trails San Francisco three games to one in the National League Championship Series.

"We like to play with our backs against the wall," Phillies manager Charlie Manuel said. "I think we're standing there right now."

There was almost no scenario predicted before this series in which the Phillies would be the team entering Thursday's Game 5 potentially one loss away from going home. They are, after all, the two-time defending NL pennant winners who finished the season by going 27-8 in their final 35 games, a staggering winning percentage of .771.

While the Phillies swept through the Reds with ease, the Giants, who are making their first playoff appearance since 2003, eked out three one-run wins in the NLDS against the Braves and had gone three weeks without scoring as many as five runs.

But the Phillies have every right to remain confident, and the biggest reason why is a 6'6" Cy Young winner named Roy Halladay.

"I'm expecting Roy's going to be great," Philadelphia shortstop Jimmy Rollins said, "and I bet he's expecting to be great."

Added closer Brad Lidge, "I know it's hard to understand how confident we are, but we've got Halladay, [Cole] Hamels and [Roy] Oswalt still to go."

Rather unexpectedly, those three aces are the Phillies' three losing pitchers of record, after Halladay and Hamels lost their starts in Games 1 and 3, respectively, and Oswalt lost Game 4 in relief.

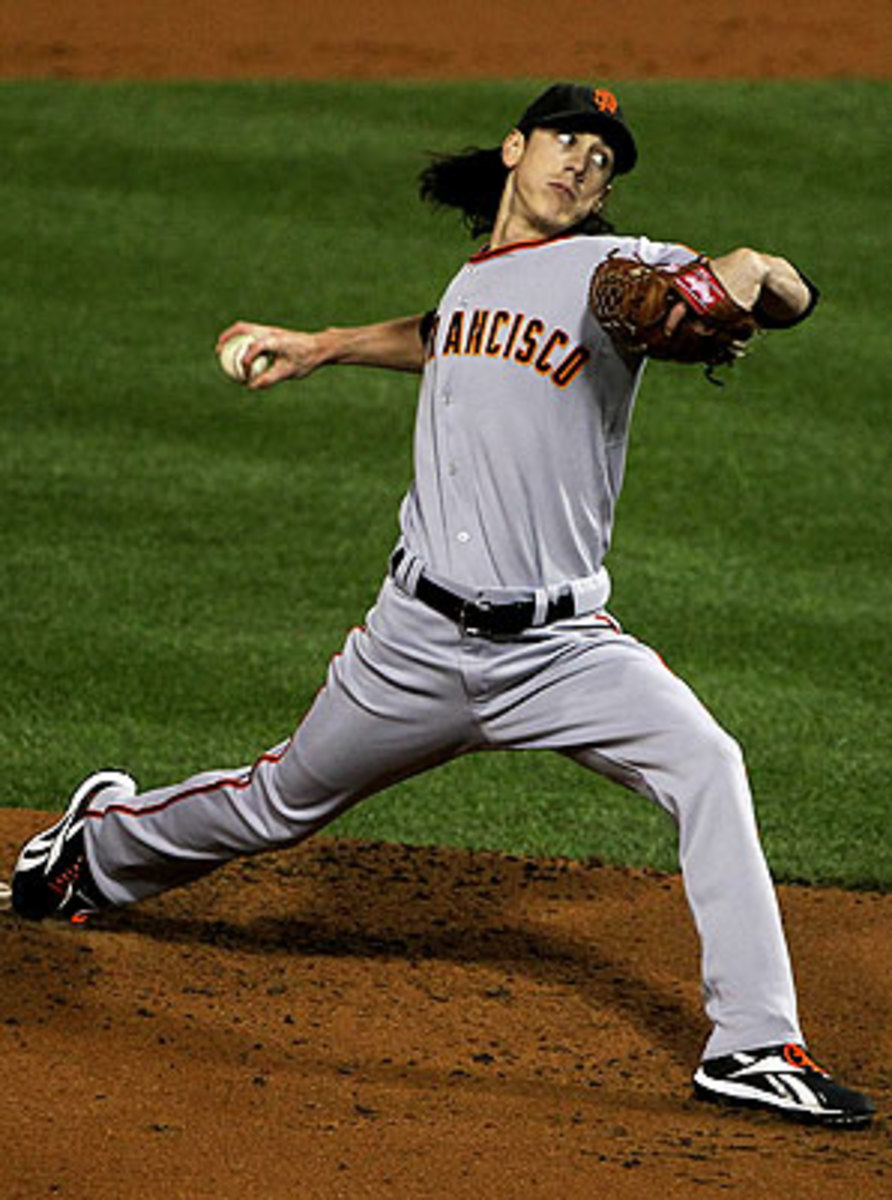

The catch, of course, is that the pitcher Halladay is opposing -- only a fellow Cy Young winner named Tim Lincecum -- already beat him in Game 1. That first meeting carried the fanfare of the most anticipated postseason pitching matchup in years, if not decades. That spark is now gone because there are not multiple off days for media-generated hype and because the 4-3 final score of Game 1 was much higher than anticipated.

Both starters were fine, but neither followed up their historic first-round performances. Halladay threw the second no-hitter in postseason history against the Reds in the NLDS but gave up four runs in seven innings to the Giants.

"I wasn't happy with the job that I did," Halladay said of NLCS Game 1, "and obviously with the end result."

Lincecum set a franchise playoff record with 14 strikeouts in his two-hit shutout over the Braves, then allowed three runs over seven innings against the Phillies.

This time the two meet in San Francisco's spacious AT&T Park, its cavernous playing field known for depressing offenses, thus making it a venue that could enhance the Cy Young rematch. At the same time, these are teams in different divisions who in the days of an unbalanced schedule only played each other six times in the regular season this year. Lincecum has only made eight starts against the Phillies in four seasons; Halladay, an AL ex-pat, has only made two starts against the Giants in the past six seasons.

Thus the familiarity of seeing a pitcher a second time could help the hitters.

"If you don't see a guy regularly, sometimes you're guessing at his pitches," Rollins said. "We'll have a better idea this time around."

Lincecum, however, has been reinventing himself regularly, recently featuring a less-than-two-months-old slider. Also, in the NLDS he threw primarily fastballs (72 of his 119 pitches) while throwing his changeup only 18 times. In his NLCS start he threw just 55 fastballs among 113 pitches but leaned heavily on his changeup, which he threw for 34 pitches.

Now The Freak has the chance to win a clinching game and advance to the World Series in his first postseason.

"I mean, it's crept in the back of my mind, obviously, just because I've never been here before and those are the things that people dream of," Lincecum said. "I'm sure everybody in here has."

The sequel carries more importance than the original duel, not only because the stakes are higher later in the series but also because both bullpens are taxed after a Game 4 in which nine relievers were used. The pitchers themselves have tried distancing themselves from the matchup because they are facing each other's lineups more than the other starter. Before Game 1, Lincecum ducked a question by joking that he'd only face Halladay two or three times -- when the pitcher's spot of the lineup cycled through.

Asked about it again on Wednesday, Lincecum drew laughter by reminding the room, "He got one hit off me." Otherwise, he insisted, "We're just approaching it like a regular game."

After the Giants' dramatic walkoff win on Wednesday, Lincecum exited the clubhouse quietly, donning a gray knit sweater and matching-colored sweatpants and completing the outfit with noise-canceling headphones linked up to his iPad. In the playoffs, the next day's starting pitcher's media obligations are completed before the prior game, so after Lincecum left, it was up to his teammates to add their votes of confidence.

"I'm pretty excited he's got [the ball]," closer Brian Wilson said. "He's our ace."

Across the way, Lincecum's counterpart similarly kept to himself. Halladay carried a plate of pasta over to the table closest to his locker in the far corner of the visitors' clubhouse, a spot beyond an imaginary line that Phillies officials had invented to sequester privacy-seeking players from the dozens of reporters filling the modest-sized space.

He sat in silence, even after Hamels came over with his own meal. Eventually the two shared a few quiet words. Occasionally Halladay's attention would drift toward the laptop Chase Utley was sitting in front of, as he reviewed tape from the day's game.

As great as Halladay has been in this season and in his career, he has never started a game in which his team could be eliminated. Then again, Lincecum has never started a game in which his team could clinch.

They are not thinking about each other, only about what's at stake: One can fulfill his dream, while the other can keep his dream alive.