Tournament of all-time greatest club teams: Part III, Quarterfinals

Editor's note: This is Part 3 of a four-part imaginary tournament between 16 of the all-time greatest club teams in soccer history. Parts 1 and 2 can be found here.

THE IDEA: Is the present Barcelona side the best team ever? The debate feels futile: this side was great going forward; this side was great at the back; this side had so many great individuals it was impossible to stop them scoring; this side was so good defensively it could stop anybody from scoring. So let's add a structure; let's design a tournament in which the best sides can compete against each other, analyzing virtual games between the best teams there have ever been. It's guesswork, of course, but at least it's educated guess work.

THE FORMAT: It was decided to admit only post-World War II clubs sides, and that each club was permitted only one entrant. This is partly because these are the sides for which information is most readily available, and partly to try to prevent any one player appearing for two different teams. To an extent the 16 is arbitrary -- certainly Millinarios '49, Benfica '62 and Boca Juniors '78 can feel a little unfortunate to have missed out, and there are those who would argue for, say, Liverpool '77 over Liverpool '84.

THE RULES: The teams were randomly drawn into four groups, each team playing each of the others once, the top two from each group to qualify for quarterfinals. The teams that qualified for the quarterfinals were as follows:

Ajax '72 vs. Liverpool '84Bayern '74 vs. Santos '62Real Madrid '60 vs. Milan '89Barcelona '11 vs. Independiente '74

Here's how the games played out:

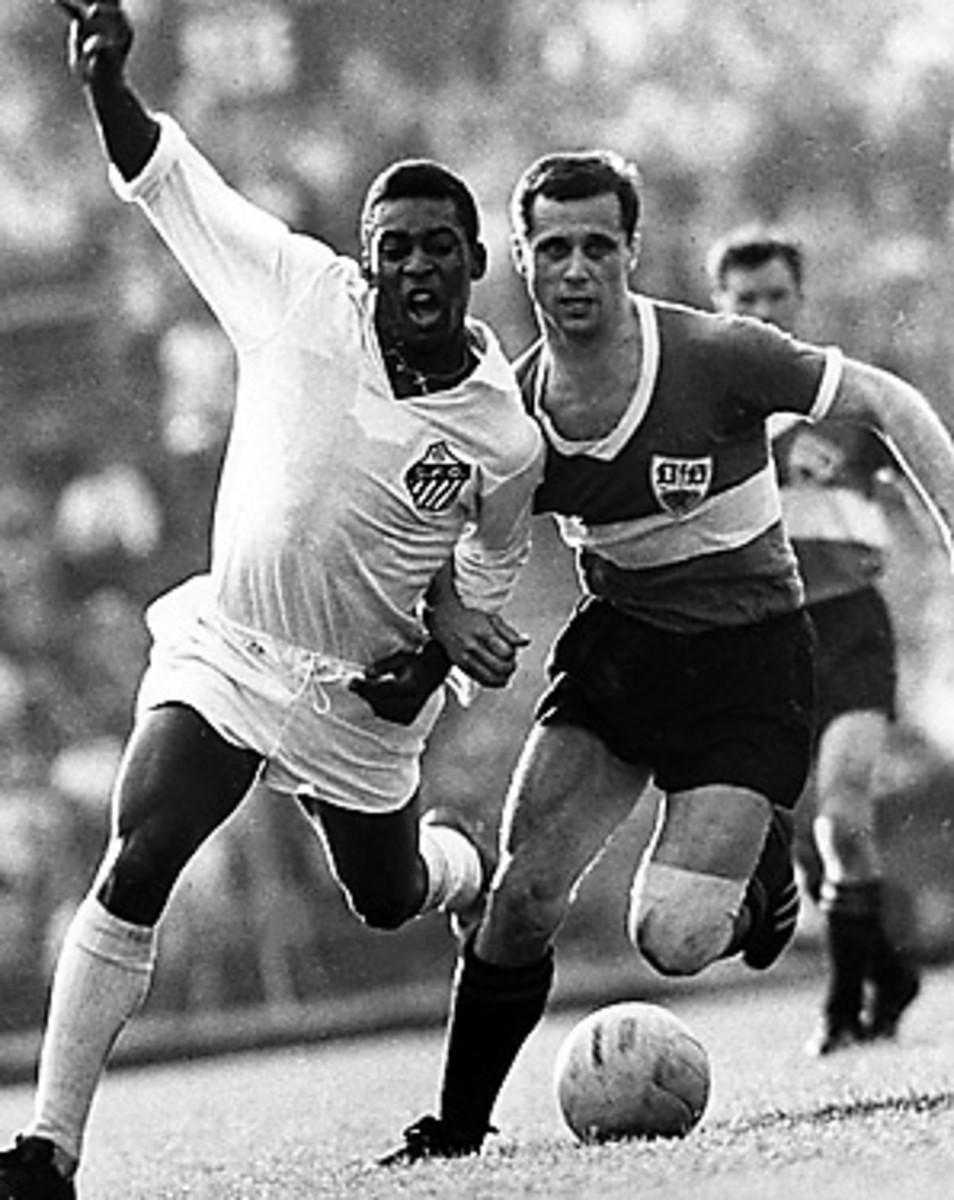

The battle everybody wanted to see, Pele against Franz Beckenbauer, ended up being something of a damp squib, as one canceled the other out. Tightly marked by the libero, Pele was rarely involved in a creative capacity, but his movement meant Beckenbauer was rarely able to get forward to support the midfield. Bayern, with the extra man in the center of the field, dominated that area anyway. While Santos looked occasionally dangerous when it got the ball wide, particularly when Dalmao and Calvet got forward from fullback, there had been a sense that a goal was imminent when Bayern's Gerd Muller turned on a Jupp Kapellmann cross eight minutes before halftime.

Dorval had been forced deep by Paul Breitner for much of the first half, but early in the second he found space as the fullback was drawn by an overlapping run from Dalmao. His cross looked too close to Sepp Maier, but the goalkeeper and Georg Schwarzenbeck got in each other's way, and as the ball broke loose Countinho was on hand to jab it over the line from close range. For a time it seemed Santos may take control, but in the end Bayern's advantage in midfield proved decisive. The winner came 12 minutes from time, as Schwarzenbeck, no Beckenbauer but comfortable enough with the ball at his feet, advanced, exchanged passes with Uli Hoeness and carried on his run. As Mauro came to close him down, Lima went with Muller, and the center back slipped the ball through for Kappellmann cutting in from the left to score with a neat angled finish.

Two teams committed, in different ways, to attacking soccer, produced an epic. For a time, early on, it seemed that Madrid might overwhelm Milan, as it attacked in waves, with Paco Gento troubling Mauro Tassotti even if Alfredo di Stefano and Ferenc Puskas struggled to find their usual space between the lines of midfield and attack. Twice the offside flag checked promising Madrid attacks, Milan's high line a tactic undreamed of in 1960. The pressing of the away side also troubled Madrid, and it was a moment of panic from Jose Santamaria that gifted Milan a 32nd-minute opener. Closed down by Ruud Gullit, he turned inside, only to find Marco van Basten bearing down on him. The Dutchman won possession, ran on and smacked a low finish past Rogelio Dominguez.

Madrid's control of possession carried on in the second half, but it was Milan who seemed to control position, forcing Madrid to play away from goal. Just after the hour, though, a quicksilver exchange between Puskas and Di Stefano worked an opening for Gento, and when he sent over a low cross Di Stefano had got forward to turn the ball in at the near post. As the game opened up both side had chances. Luis Del Sol clipped the outside of the post with a low drive, and Van Basten headed a Roberto Donadoni cross just over, but the longer it went on, the more the attritional approach of Milan, harrying its opponents to distraction, began to give it the edge. Arrigo Sacchi's side couldn't make that tell in normal time, but shortly after halftime in extra time, Angelo Colombo won a corner on the Milan left. The delivery was good and when Van Basten's initial header was blocked, Frank Rijkaard poked the loose ball over the line.

When Ajax beat Bill Shankly's Liverpool 5-1 in 1966, there was a sense Liverpool had been caught unawares. Here, although forewarned about Johan Cruyff, it proved just as unable to stop him. This was a master class from the archetypal false nine, repeatedly dragging the Liverpool center backs out of position, encouraging a swirl of movement that would surely have resulted in further goals had Ajax not been content to hold possession and protect the lead given them after 17 minutes by Ruud Krol. The left back got behind Phil Neal and sent a rasping shot in off the underside of the bar after Arie Haan, moving into the space vacated by Cruyff, had picked him out with an astute reverse pass.

Ian Rush did have the ball in the net just before halftime, only to be ruled narrowly offside as he ran on to a Dalglish through-ball, but although Lee's use of the ball was as tidy as ever, Liverpool looked a little toothless as Graeme Souness was neutered by Johan Neeskens. Both midfielders put in crunching challenges on the other, and in a later era both may have received worse than the yellow cards they picked up in quick succession for fouls midway through the second half. The use of Ronnie Whelan narrow on the left perhaps restricted Ajax to an extent, but it also meant that Liverpool's only width came from Craig Johnston, and the Australian never looked like getting the better of Krol. This, though, was Cruyff's match, a wonderful game of intelligent pass-and-move soccer in which the master of soccer's geometry asserted his superiority.

Briefly it seemed there may be a major shock at the Camp Nou. Only two minutes had gone when Ricardo Bochini found Austin Balbueno in space behind Dani Alves. As Carles Puyol moved across to close down the winger, Bochini continued his run, took the return from Balbueno, stepped inside Gerard Pique and curved a precise finish past Victor Valdes and in off the right-hand post. But the game soon settled into the familiar pattern: Barca circulating possession as its opponents packed men behind the ball and sought to close off the space. If Independiente had held out till halftime, perhaps Barca might have begun to doubt itself, but a minute before the break Messi jinked away from Alejandro Semenewicz and at last found room in front of the back four. As Francisco Sa and Miguel Angel Lopez both went to close him down, the Argentine slipped an angled ball outside him to David Villa cutting in, and his first time shot from just inside the box flashed into the top corner almost before Carlos Gay had set himself.

As Independiente tired, it became just a matter of time before the score line began to reflect Barca's domination. The goal that gave Pep Guardiola's side the lead just before the hour was controversial, Pedro going down under Ruben Galvan's challenge right on the edge of the box; the referee gave the penalty, and Messi converted calmly. Both he and Villa then hit the woodwork before Puyol made the game safe five minutes from time, heading in a left-wing corner.

Jonathan Wilson is the author of Inverting the Pyramid; Behind the Curtain; Sunderland: A Club Transformed; and The Anatomy of England. Editor ofThe Blizzard.