Penn State tragedy shows danger of making coaches false idols

If college athletics held its proper place in the greater landscape of higher education, there would have been no reason to congratulate or criticize Brand. In other walks of life, it's not considered courageous when the head of a business dismisses one of his subordinates for inappropriate behavior. The Brand-Knight incident was only jarring because for the previous 30 years, the power dynamic between Indiana's president and basketball coach had been reversed.

Nothing about college coaches' skewed importance has changed since then. If anything, it's gotten worse. Head football and basketball coaches now make as much as five times more than they did just a decade ago, and the media coverage surrounding them has amplified accordingly.

But if there were ever a time for fans, media members and college administrators alike to get a collective wake-up call, it's following Joe Paterno's dismissal. No football coach has ever lorded over an entire university the way Paterno did during his 45 years in State College. And no university has suffered a more gruesome football-related episode than the ongoing Jerry Sandusky child molestation scandal.

The mess at Penn State has illustrated the danger of putting successful coaches on pedestals. Four wins or 400, coaches are still people, and people aren't perfect. That's why our government employs a system of checks and balances, and why businesses nationwide mimic that distribution of power.

At Penn State, Paterno had all the power. President Graham Spanier and athletic director Tim Curley were technically his bosses, but they held as much sway over him as the guys selling hot dogs at Beaver Stadium on Saturdays. We know this most vividly because in 2004, Spanier and Curley tried to push out the struggling 77-year-old coach, and Paterno told them ... no.

That distorted dynamic is why Sandusky was allowed free reign of the Penn State football complex years after the first account of sexual molestation surfaced. Who was going to stop him if not Paterno?

Many think Mike McQueary should have. According to his grand jury testimony, McQueary, then a 28-year-old graduate assistant, witnessed Sandusky raping a boy estimated to be 10 years old in the locker room showers. How, people ask, could a grown man like McQueary fail to step in and stop this atrocity when he saw it? Why did he not call the authorities?

In McQueary's world, Paterno was The Authority. McQueary, a State College native, former Penn State quarterback and son of a huge Nittany Lions fan, has spent nearly his entire life in a warped world few of us understand. What some view as cowardice probably seemed courageous to McQueary at the time: He went to The Authority's house and relayed bad things about the coach's long-time trusted confidant. He didn't know The Authority would merely pass the information along to his two in-name-only superiors, who then failed to take substantive action.

What's far more puzzling is how McQueary went to work for the next nine years and accepted seeing Sandusky at practice or in the weight room. But the Penn State football complex wasn't a normal workplace; the lone Authority was out to lunch in his last years on the job, but he held such clout that few dared to question his actions. That's not an excuse for McQueary's decisions, but it's reality -- a sick reality in which inaction was the norm.

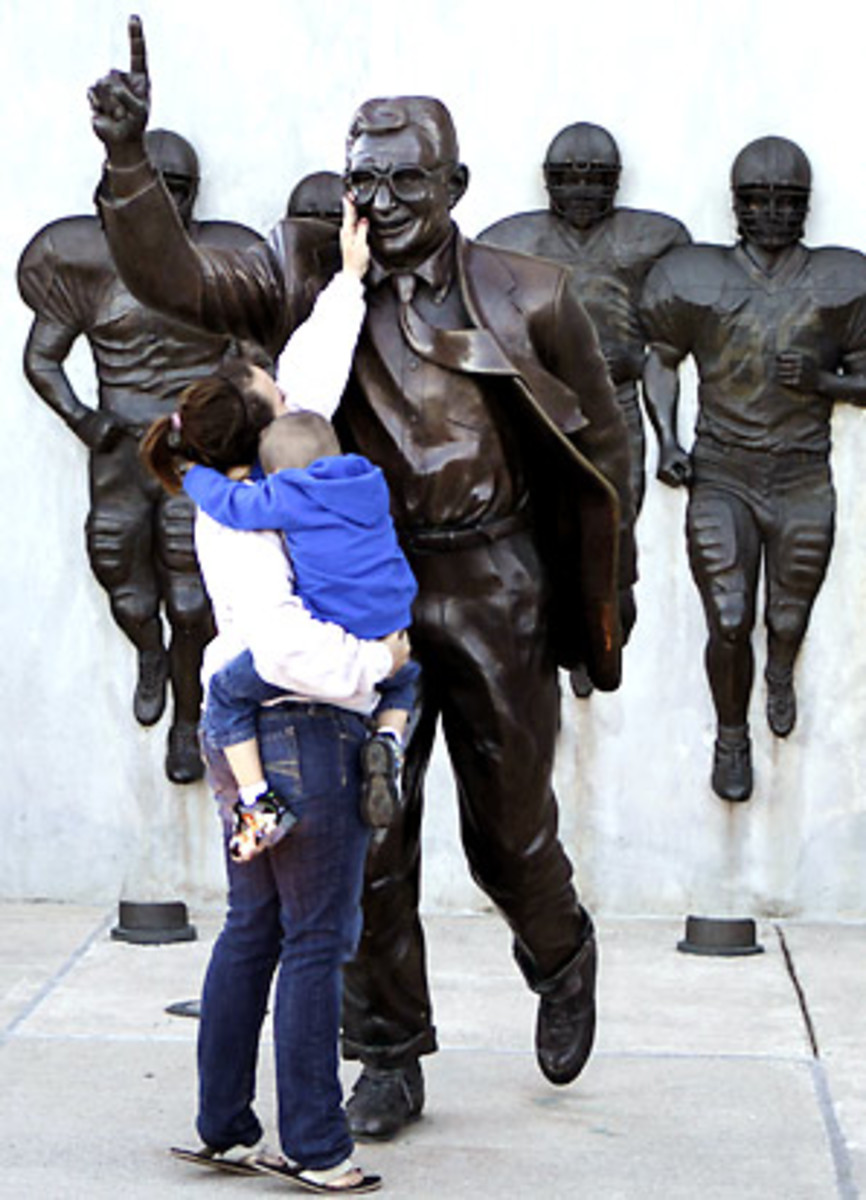

Paterno and his so-called bosses deserve all the blame we can muster for allowing this atrocity to occur, but the rest of us deserve blame for lionizing coaches like Paterno in the first place. We turn these mortal men into irreproachable icons. We do it with articles portraying them as something more mystical than people who happen to be good at their jobs. We do it by camping out for tickets in tent villages named in their honor. We do it by building statues of them while they're still on the job.

Few actually rise to the realm of idolatry, but any major college football or basketball coach who has sustained success enjoys unprecedented power. The truly revered have presidents and athletic directors who theoretically sit above them but in reality work for them. They enjoy blindly adoring fan bases that would raise arms at the mere suggestion of wrongdoing.

Sports are our escape, so it's not surprising that we treat our favorite figures like movie stars. But as we were reminded so painfully this week, this is real life. And unlike professional coaches, who work for businesses tasked solely with winning athletic contests, college coaches are theoretically part of a greater community, where education is supposed to trump entertainment and leadership is supposed to be more than a Big Ten Network infomercial.

There's nothing wrong with going to a game, painting your face or cheering on your favorite team's coach for hours. There's nothing wrong with me writing an article praising a coach for his inspired gameplan. There's nothing wrong with a school president giving a championship coach a raise.

But there's something inherently wrong with a community in which one person holds an inordinate amount of power. Teachers answer to their principal. CEOs answer to their shareholders. Mike McQueary answered to Joe Paterno.

Paterno didn't answer to anybody. No coach has ever experienced a more painful downfall, in part because no coach had ever been elevated to such heights.

Hopefully, no coach ever will be again.