Maddon, Gibson highlight problems with Manager of the Year award

As I wrote last August, it's nearly impossible to measure the impact a manager has on his team. In fact, it seems likely that the best manager in baseball may not be worth much more than five wins (if that) over an average one, which is roughly the impact of the game's best middle reliever, and no one is handing out any hardware to those guys this week.

As a result, the Manager of the Year award is -- or should be -- used as a symbol of sorts to award impressive team performances, performances that have as much or more to do with how well the general manager, coaches, and, of course, players, did their job than how well the manager did his, be it in the clubhouse or between the lines.

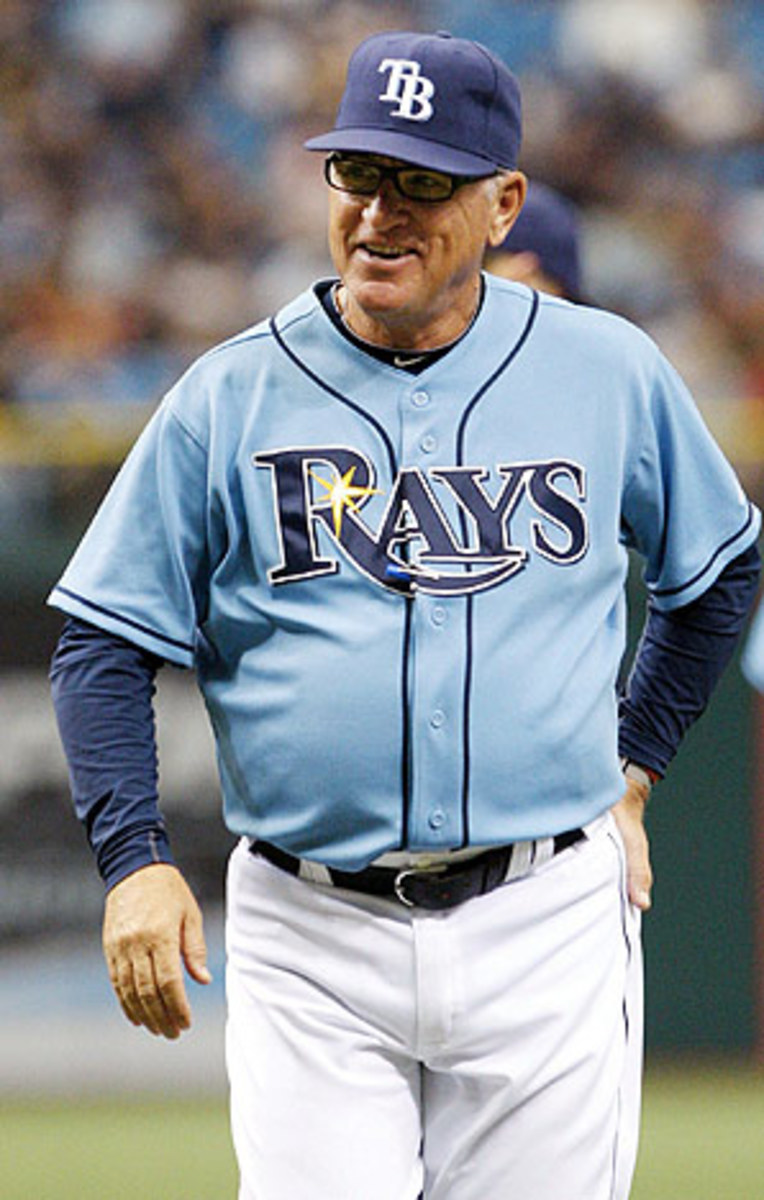

That is not to say that this year's winners, the Diamondbacks' Kirk Gibson in the National League and the Rays' Joe Maddon in the American League, were not deserving of the awards by the traditional metrics used to decide them. Indeed, both men fit the profile of past winners by having led their respective teams to the playoffs, as have almost 90 percent of Manager of the Year winners.

A closer look, though, reveals some of the curiosities of this award. Maddon, for instance, is just the fifth man to win it after seeing his team lose more games than it did the previous season; Tampa Bay won 96 games and the AL East in 2010 but fell to 91 wins and the wild card in 2011.

What's perhaps most interesting about Maddon's triumph is that had the Rays won just 90 games -- still an impressive feat -- it might have been Jim Leyland of the Tigers who would be celebrating his third Manager of the Year award. However, the Rays did win 91, completing a furious comeback for the wild card by winning an 11th inning thriller against the Yankees' B team on the last day of the season and thus likely vaulting Maddon past Leyland, whose team cruised into the playoffs, for the award. That would seem to speak to the fact that this award was not so much earned over the long haul of a six-month season but in the much shorter, though more pressure-packed, final days.

If that seems strange, consider the case of Gibson. A former NL MVP with the Dodgers, Gibson drew much praise for "changing the clubhouse culture" and thus helping convert the Diamondbacks from 97 losses in 2010 to 94 wins in 2011. What you'll hear most about Gibson as a manager is that he demanded accountability from his players and brought intensity that was lacking to the clubhouse. We heard much the same thing about Buck Showalter when he had the Orioles playing close to .600 ball down the stretch in 2010, but that phantom disappeared over the winter as the Orioles went back to being a last-place ballclub. Similarly, Gibson didn't have much more success than his predecessor and former boss A.J. Hinch after being promoted from bench coach to replace Hinch on July 1 of 2010, posting a .410 winning percentage over the remainder of the year to Hinch's .401.

Arizona's 29-win improvement, which tied for the fourth-largest year-to-year improvement by a Manager of the Year winner in either league, was no doubt impressive but a manager alone cannot effect that kind of change. In truth, Arizona's turnaround was due as much if not more to the moves of his general manager, Kevin Towers, who transformed one of the worst bullpens in baseball in 2010 into a strength last season, and to career years from players just entering their primes (Justin Upton, Ian Kennedy, Miguel Montero).

That's not to say that Gibson didn't have an inspirational effect on the D-backs -- whatever impact a manager can give to his team in that area, it's quite clear Gibson gave it -- just that that is not the only or even biggest reason Arizona won the NL West. More specifically, he did an excellent job of avoiding a negative tactical effect on his team, calling for the fewest intentional walks (tied with Manager of the Year runner-up Ron Roenicke of the Brewers) and sacrifice bunts (50, just 17 by non-pitchers) in the National League this year, proving that he knows the value of outs and baserunners on both sides of the ball.

Maddon has long been credited for having a similarly positive influence but he also benefited from the decisions of those around him, specifically the front office that had a plan to make up for a slew of offseason departures. Indeed, Tampa Bay was not nearly as decimated by roster turnover as popular thinking had it. For instance, the Rays only traded starting pitcher Matt Garza to the Cubs because they had Jeremy Hellickson, who was just named AL Rookie of the Year on Monday, ready to step into his spot in the rotation. The departure of Carlos Peña, who hit just .197/.325/.407 in his final year in 2010, was mitigated by the strong defense and .306/.378/.422 hitting of Casey Kotchman, who was a non-roster invitee to spring training and opened the year on the bench. And Carl Crawford's move to the Red Sox with a seven-year, $142 million contract was lessened by the arrival of rookie Desmond Jennings. In hindsight, that deal already looks so bad that Boston GM Theo Epstein fled to the Cubs in part to escape it.

Maddon and Gibson both can be proud of their roles in guiding their teams to the postseason. But they would surely be the first to admit that they didn't do it alone, and that while today's announcement honors them it really should honor their entire organizations.