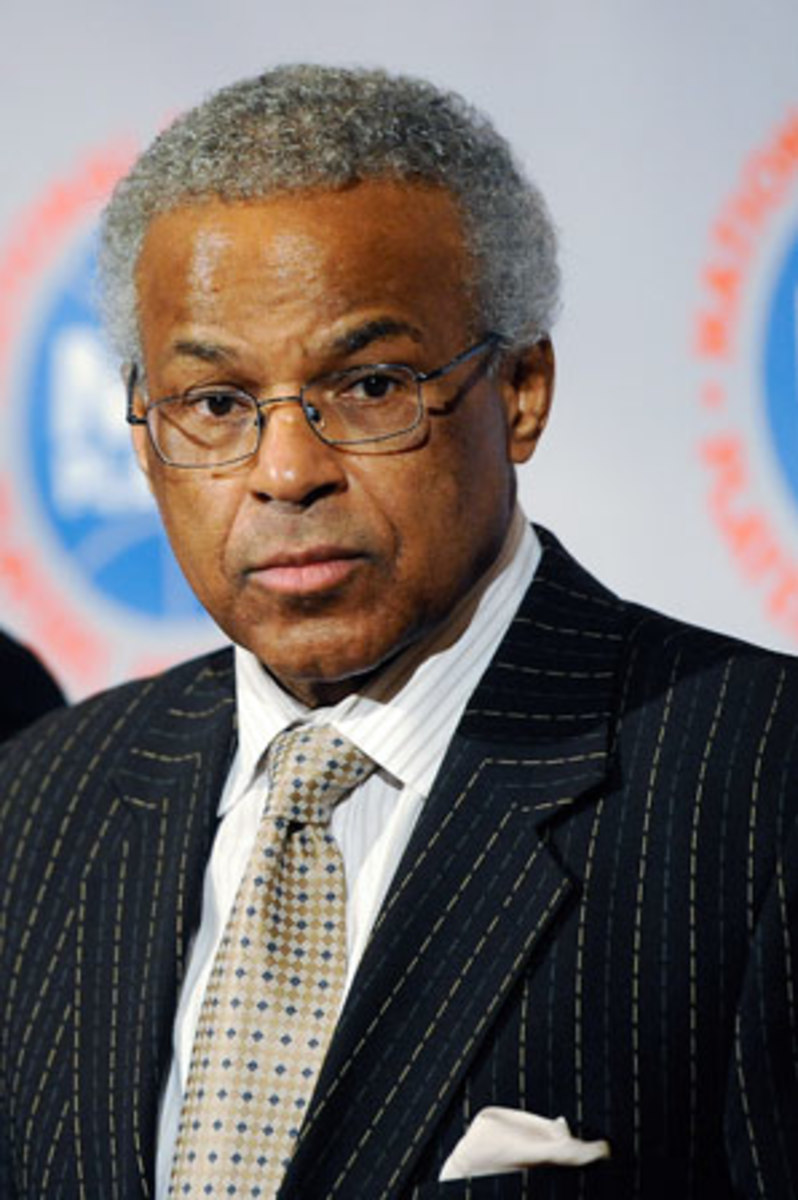

NBPA's Hunter 'couldn't care less' about scrutiny from players, agents

As National Basketball Players Association executive director Billy Hunter sees it, the truth about the NBA's new collective bargaining agreement won't be known for quite some time. Reserve your judgment until this summer, he said during All-Star weekend in Orlando, when a season will be in the books and a second, less hectic round of free agency will be far more revealing than the first.

But Hunter's critics have never been the patient sort. From the seven power agents who hoped to unseat him during the lockout, to the players who seethed when he refused to forgo his multi-million-dollar salary when they had lost theirs, Hunter was and remains a marked man in the eyes of some. A former U.S. Attorney and pro football player who took over the NBPA in 1996, the 69-year-old Hunter survived his second work stoppage despite an onslaught of private attacks.

He's too insular, his critics said, too quick to make enemies out of agents who should be his allies and protect himself rather than his players. He even battled with his own, as the later stages of the lockout included a rise in tensions between Hunter and top player representative, Derek Fisher, that remain.

And now, the most uncomfortable of dynamics remains, too. Because Hunter signed a contract two years ago that doesn't expire until 2016, his most influential work is done long before his deal runs out. The 10-year agreement in which the players gave back approximately $3 billion combined includes a mutual opt-out after six years that is almost certain to be exercised by one or perhaps both sides, meaning the next round of negotiations will take place in 2017.

Some players and agents will shrug at this reality, the fact that their top leader appears safe no matter how low his approval rating goes. Yet others are privately resentful, angered by the idea that he still leads the union, and are determined to keep the target on his back.

"You'd have to ask the people who supposedly put it on there, whether or not it's still on there or not," Hunter told SI.com. "I don't even think about that. I do my job. I'm under contract. That's it. I don't take it personally. People have a right to their opinions.

"I try to be pretty insular. I have friends, people that I confide in, people I trust. And that's what I do. I know a lot of this is motivated by other folks, so I don't let it bother me. I couldn't care less."

Now that the long nights in hotel conference rooms are over and NBA commissioner David Stern is again a friend rather than a foe, there is plenty that pleases Hunter.

"I'm trying to spend as much time as I can with my grandchildren," he said. "I don't know how much more time I got left on this planet, so I don't think that far ahead. I'm hoping that I can get these four [years] in."

While Hunter has emphasized the importance of raising salaries for the NBA's middle-class -- and, to some, securing his status among the masses as a result -- some of the league's most powerful agents and their star players argued for a Darwinian system in which the elite faced no financial ceiling. The divide grew quickly after Hunter's arrival, with former power agent David Falk leading the charge 14 years ago by way of his client, then-NBPA president Patrick Ewing, and fellow agent Arn Tellem, who was part of a group of seven agents (not including Falk) pushing for decertification of the union last year.

At the start of the 2011 lockout, sources say even Hunter's most ardent critics told him they would attempt to keep him at the front of this fight if that aggressive tactic was taken. But over time, it became clear that he would be marginalized -- albeit while still being paid -- if decertification took place.

But Hunter staved off that push, eventually opting for an alternative on Nov. 14 -- disclaiming interest in the union -- that not only preserved his power but was followed by the end of the lockout 18 days later.

Those who know Hunter best say the '98 experience had everything to do with how he handled the latest challenge. He ignored most agents and focused on the players, his favorite refrain for reporters to come tell him when his most important constituents -- the players -- were publicly complaining. But aside from a late-November bashing from then-Mavericks guard DeShawn Stevenson, the campaign to push him out was mostly private.

"It was [intense], but that's the nature of the beast," Hunter said. "I mean you understand that when you take the job."

As for the CBA, it has much in common with the union head himself: It's in place, whether its critics like it or not.

"You have to play the hand that's dealt to you, and we entered into the agreement and so we have an obligation to live by it, to honor it," Hunter said. "I think we probably won't [know how good of a deal it is] until next summer, until the end of the season. When we see how the signings go in the summer, then we'll know whether the deal is everything that we thought it would be."