Notable one-club players in England a rare breed in modern era

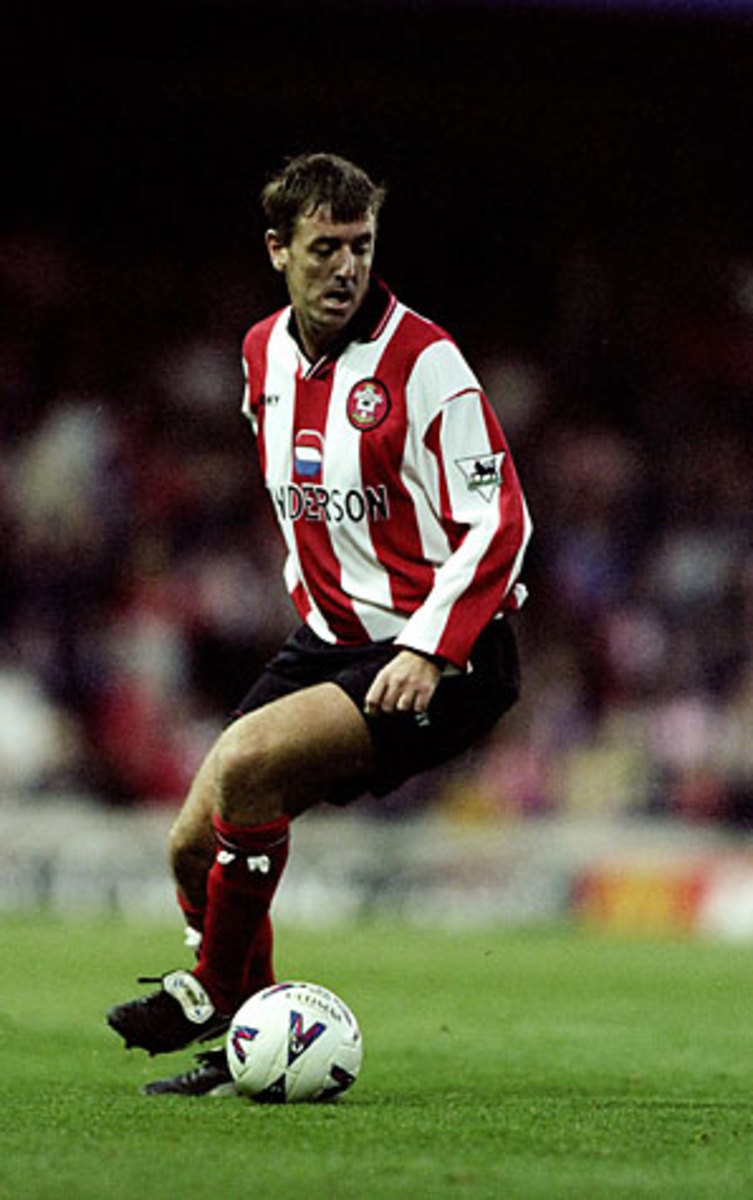

The last truly exceptional talent to stay at an unfashionable club, Le Tissier played 540 matches for Southampton, scoring more than 200 goals (plenty as wonderful as this) and never banking a basic salary above £4000 ($6351) a week, even in the Premier League era. He was absurdly gifted with a ball at his feet -- Barcelona midfielder Xavi has described Le Tissier as his childhood idol -- yet never won a trophy, and was called up only 11 times by England, making eight appearances.

"I've no regrets whatsoever," he later said. "I knew I probably wouldn't win any honors, but when you're at a club that size, staying in the Premier League for 16 years gave me as much pleasure as winning a medal. I was so chuffed to be a part of that." After Southampton flirted with relegation in the 1995-96 season, the sacked manager, Dave Merrington, said Le Tissier should have moved years earlier "to a bigger club, where he would have been on mega-money." Le Tissier, a Spurs supporter, pulled out of a move to Tottenham in 1990, and later turned down a £7 million ($11M) move to Glenn Hoddle's Chelsea. "I enjoyed being a big fish in a medium-sized pond," he explained. "The person in the team that most fans were coming to watch, just to see if I could do something." He usually could.

Written off by Sunderland (the club he grew up supporting), Tottenham and Wolves for being too small, Paisley joined Liverpool at 20, and over the following half-century fulfilled the role of player, physio, manager, adviser and director. He married tenacity and intelligence in a left-sided midfield role, and helped Liverpool to win the league title in 1946-47, the first full season played after the second world war. That was the only winners' medal Paisley picked up as a player, but he went on to be the club's most successful manager, winning six league titles, three League Cups, the UEFA Cup, the European Super Cup and three European Cups between 1974 and 1983.

Paisley was and remains "Mr. Liverpool," which makes the summer of 1950 a pivotal moment in the history of the club. That year Liverpool contested the FA Cup final with Arsenal, thanks in part to Paisley's goal against Everton in the semifinal. He had been injured between then and the final, and despite being passed fit, wasn't picked to play at Wembley. Arsenal's Reg Lewis -- who had himself been in and out of the side but was picked, as the London club looked to avoid a third defeat to Liverpool that season -- scored twice to keep the trophy in London. Paisley was devastated, describing it as the only point at which he felt his feelings about the club change. He resisted speaking out, despite being offered cash for his story by at least one newspaper. "I have lived to bless the day when I bit my tongue," he said, and he certainly wasn't alone. "I didn't want to move really."

Ticker Froggatt's father Frank captained Wednesday to promotion in 1926, but requested a transfer after losing his place at the start of the club's first season back in the top flight. It was a decision he always regretted, and made sure to impress that upon his son. "My father had simply said to me: 'If ever you get in with Wednesday, stick with them'," Redfern told Keith Farnsworth, in Wednesday Every Day of the Week. "And I was determined to do just that." He made 550 appearances for the club, ignoring interest from seven other scouts who tried to sign him from Sheffield YMCA, and later from representatives of Newcastle United, Spurs, and Fiorentina.

Froggatt had grown up close to the ground, despite his father's move to Notts County. Living close to a number of Wednesday players, including his idol, Jackie Robinson, he would follow them around trying to walk the way they did, and hoping he might one day do the same on a soccer pitch. He went on to score around 170 goals for Wednesday -- making his goals-to-games ratio not much different to Robinson's official league record -- and reluctantly retired after a couple of seasons in the reserves. "Playing for the club you supported was special," he said, having only turned professional because his celebrity status made it difficult to get "proper" work locally. "I was lucky, and, frankly, I'd have played for nothing."

Wanderers have recently announced plans to build a statue of Lofthouse outside the Reebok stadium in recognition of a lifetime devoted to the club as player, coach and president. It was at their former home Burnden Park that Lofthouse first took notice of Bolton - climbing up a drainpipe to get in to watch matches as a boy -- and where he made his debut, aged 15, against Bury. He scored his first two goals for Bolton in a 5-1 victory that day, and added 283 more in over 500 appearances before retiring in 1960. Though he was not that tall, he was 12 stone (168 pounds) of pure muscle, working as a miner during the war. Unceremoniously told he had no artistry on the ball (he admitted he was initially a "limited" player), he worked at getting faster, shooting harder, and heading the ball with the accuracy of a snooker cue. He reveled in a game where "plenty of fellas would kick your bollocks off", so long as they were good enough to "help you look for them" at the final whistle.

Adams was appointed Arsenal captain in 1988, aged just 21, and in the next 10 years the club would go on to win two First Division titles, a further FA Cup, two League Cups and the European Cup Winners' Cup. Midway through the 1997-98 season, however, Adams' form dipped so drastically thanks to an ankle injury that he considered moving to another club, and when he couldn't countenance that (although, as an aside, he was one of those who argued that Le Tissier ought to have switched clubs), he and Arsene Wenger talked about a summer retirement. It says a great deal about his relationship with his manager and his club that just six months later, in May 1998, he lifted Arsenal's first Premiership trophy, and the FA Cup.

Adams' problems with alcohol have been well-documented, and in his autobiography, Addicted, he quotes a rueful Wenger. "I cannot believe how you achieved everything you have with the way you abused your body and your mind. You have played to only 70 percent of your capacity." The manager never lacked faith in his captain, however, and it was he who sent Adams to France where he recovered from the ankle injury and returned to help Arsenal win 13 of its last 16 league games of the season -- beating Manchester United to the title by a single point -- as the team won a domestic double for the second time in its history. Adams retired after the third, in 2002.

Barrett's England career was even shorter than Francis Jeffers', injured after four minutes of his appearance against Northern Ireland in 1928, but he was a stalwart of Syd King's West Ham side in the interwar period, playing an estimated 500-plus matches. Having waited two years to make his first-team debut, the Stratford-born player didn't miss a game between 1925 and 1927, featuring in almost every position -- including one match in goal -- along the way. Typically a defender, he wasn't bad up front, either, and managed to score a hat-trick when drafted in to the front line against Leeds United in 1926. Twenty years later he played alongside his son, Jim Jr. for West Ham's reserve team, which he coached.

Nicholson signed for Spurs as a 16-year-old boy and was club president when he died almost 70 years later, with fans still campaigning to have him knighted. In the meantime he had made 345 appearances (switching from inside forward to half back during the Second World War), served as head coach, and won eight trophies as manager, including in 1963 the first major European trophy won by a British side, and Tottenham's remarkable domestic double in 1961.

Later as a consultant -- effectively director of football -- he was credited with spotting players such as Glenn Hoddle, continuing his influence on the way Spurs play and the club's philosophy, which holds even now. "He did not create the dominant side of an era that would fairly place him with Bob Paisley, Jock Stein, Brian Clough and Sir Alex Ferguson in the front rank of the British game," said the Telegraph's obituary. "Yet, even at the height of their success, none of their sides could match Nicholson's for the élan with which they performed week in and week out."

Georgina Turner is a freelance sports writer and co-author of Jumpers for Goalposts: How Football Sold its Soul.