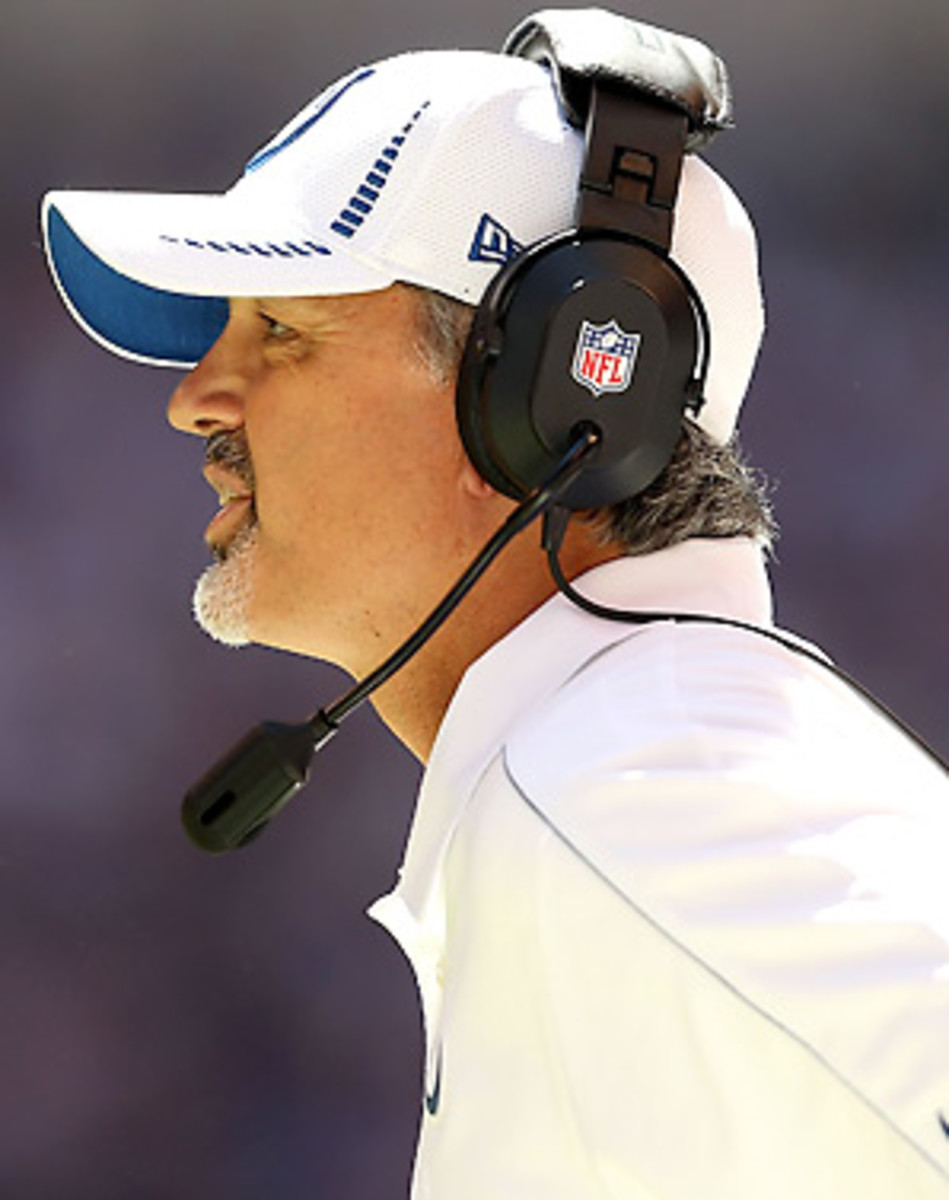

For better or worse, Pagano will forever be changed by diagnosis

There's nothing that can prepare you for the words you'll hear in that room. It doesn't matter if you're sitting there alone or with family. It doesn't matter if you're young or old. It doesn't matter if you know it's coming. There's a reason you find yourself sitting in that room, inside that hospital, when a doctor walks into the room. Doctors know to make eye contact, to show some empathy, but there's nothing that can prepare you for the words you'll hear sitting in that room.

Chuck Pagano sat there late last week. A doctor at the Simon Cancer Center in Indianapolis walked in and told him the test results. Pagano likely knew. His wife had seen the unusual bruising. Maybe he'd ignored the signs. Tired? Heck, he was a new head coach in the NFL, and if he was tired, it was just all the hard work and long hours being put in at a dream job he'd desired for years. Of course he would try to tell himself that he was fine, just a virus or something.

It's the clinical words, the facts that confront you, that cause a pit in your stomach. "Acute myeloid leukemia" sounds like nothing but evil, even when science tells us it's one of the most curable forms of cancer. The diagnosis always sounds like a death sentence, and in your head, that's how you hear it: Latin roots, primal fear. The hope comes later, for most. The fight comes later, for most. In the moment, in that room, there's just a ... well, there's no words for it. You only know if you've been there.

I have. And I wonder if Pagano was in the same room that I was in 1996, in what later became the Simon Cancer Center. I had been asked to take some more tests after having a physical for new health insurance, and when I was sent to what was then University Hospital's oncology department, nothing they were going to tell me was bound to be good news. Looking back, there were signs. I had lost a bit of weight. I had gotten tired more easily. I used to umpire Little League games and would do three or four in a day, but I recall before my diagnosis getting so tired I had to switch out from behind the plate during a second game. I forget what excuse I gave them, or myself.

Pagano heard "leukemia." I had lymphoma. They are similar, but not the same. His treatment will not be my treatment and our journeys are different as well. The research done by the Simon Center and hundreds of others across the world have given the doctors there more and better options. More people that hear those words will survive. Some will go on and do great things, like one patient who was there at the same time I was. He beat testicular cancer and perhaps raised the money to help fund research that will now help Pagano. I never crossed paths with Lance Armstrong, but at the time, no one expected him to survive, let alone to "live strong." His name was mentioned in whispers, not for sake of privacy, but out of respect for his journey. Pagano won't have that.

That's not to say it will be easy for Pagano. His journey is going to be long and complicated. He'll have in-patient treatment that will make him question his own humanity, test reserves of the soul that even the brutal game of football never brought to the surface, and bring him face to face with mortality.

He'll likely be given drugs to help him make it through the symptoms and the treatment that would be illegal for his players to take, from doses of opiates to anemia fighters that are banned in every sport but are lifesavers for those with leukemia. He may need a stem cell transplant, an amazing procedure that sadly hasn't made the progress it should have, held back nearly a decade by a research freeze. He'll have the support of a team and a community, but there will be moments when he will be powerfully alone.

In the worst of those moments, vomiting so powerfully that my abdominal muscles cramped, I had my moment. I knew I couldn't do this. At 26, my mind gave in to the poison and I began to doubt everything. I wondered if it was better to die peacefully than fight. At that moment, a young girl, maybe 8 or 9, walked into the room. It's hard to be polite when you're vomiting, but we smiled. We ended up making it a game. Who could be the loudest, who could go the longest. By distracting her, I distracted myself, just long enough to forget that I almost gave up. I never saw her again and I often wonder what happened to her.

In a few months, Pagano will be back in a room. Perhaps he'll have lost some weight, some more hair, and hopefully, he'll have no cancer. That room is different and the tone of the voice giving you the news is changed. You hear words like remission, cure and release. The Latin is gone, but while the cancer cells leave your body, it never leaves your mind. Every ache or pain, especially for the first year, brings back that feeling deep in a person's soul that it's back. That part never goes away entirely.

Pagano is strong. He has some of the best doctors and care in the world. He's insured. His team and the whole league are rallying around him. The odds are in his favor, but when he does walk out of that room, returning to his office and then the sideline, Pagano will not be the same. Those words sit deep in your soul, deeper than the cancer will ever get.

That room changes you, for better and for worse.