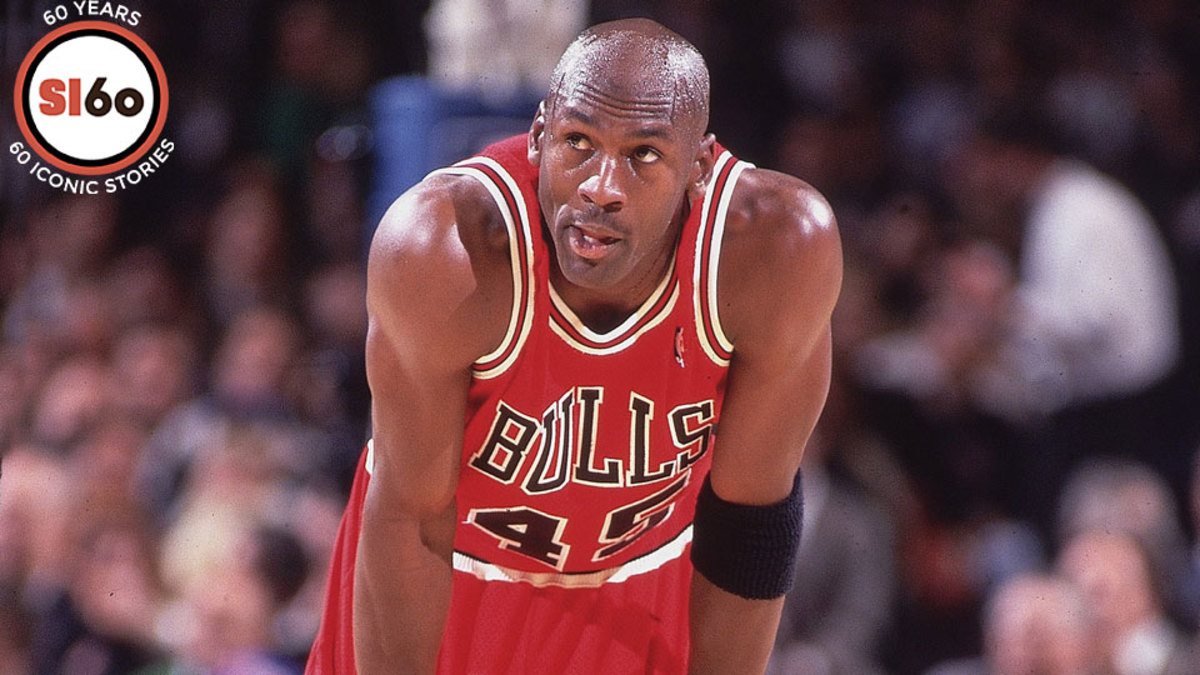

55: Remembering the night Michael Jordan announced his return to dominance

In honor of Sports Illustrated's 60th anniversary, SI.com is republishing, in full, 60 of the best stories ever to run in the magazine's history. Today's selection is on the man who has appeared on more SI covers than any other: Michael Jordan. This piece, by Alexander Wolff, was not a cover story but it perfectly recreates the night Jordan, who had just returned to the NBA after an 21-month absence to play minor league baseball, regained his throne as the league's king. It also perfectly sets up the three-year run of dominance he was about to embark on. It originally ran in the Nov. 13, 1995 issue.

There is no place like it, no place with an atom of its glory, pride, and exultancy. It lays its hand upon a man's bowels; he grows drunk with ecstasy; he grows young and full of glory, he feels that he can never die. --Thomas Wolfe, on New York City

On March 27 of this year, on a Monday afternoon flush with the balm of spring, Michael Jordan arrived in Manhattan and checked into the Plaza Hotel. That evening he and four companions, including NBC commentator Ahmad Rashad, met for dinner downtown at Robert De Niro's Tribeca Grill. These were old friends, determined to liberate Jordan from the prison of his hotel room--to "keep it regular," as Rashad says. The game that Jordan and his Chicago Bulls were to play the next night against the New York Knicks at Madison Square Garden was only indirectly alluded to, but throughout the evening Rashad sensed something about Jordan--sensed that Jordan knew that if he had something to say, New York was the place to say it.

When Jordan returned to the hotel after midnight, CBS's Pat O'Brien was waiting for a previously scheduled interview. Jordan had stood him up for more than three hours, but O'Brien had spent that time well, drawing up the most prescient of questions. "When will fans see an explosion," he asked, "the kind of game in which you score 55 points?"

"It's just a matter of time," said Jordan.

Jordan wasn't accustomed to being measured against his past. Until he stepped away from the game for 17 months, beginning in October 1993, the public had always spun its wonderment forward, asking the question, "What's he gonna do next?" But with his return, the public imagination now ran backward, and to Jordan the rephrasing of the usual question must have come with daunting psychological g-forces: Can he possibly do those things again?

And, oh, those things he had done. There had been that moment during his final season at North Carolina, in the dying seconds of a victory at Maryland, when Jordan made off with a lazy Terrapin pass and threw down a breakaway dunk stunning in its suddenness, its playfulness, its remorselessness. As Jordan sat in the locker room, his eyes intent on the latticework of his shoelaces, a reporter asked him if he had intended the dunk to "send a message."

"No messages," he replied, scarcely looking up, like an efficient secretary.

Back then Jordan had no need to gild his game with ulterior meaning. But things were different now, 11 years, three NBA titles, two Olympic gold medals, his father's murder and a bush-league baseball misadventure later. Based on the first few games of Jordan's comeback from his sabbatical in the Chicago White Sox organization, a columnist in Florida had already declared him "finished." One New York tabloid had dubbed him FAIR JORDAN. And Doug Collins, an NBA analyst for Turner Sports who had been Jordan's coach with the Bulls and soon would become coach of the Detroit Pistons, had committed apostasy. He had called Jordan "human."

So it was that, carrying a new uniform number, 45, and these fresh burdens, Jordan found himself in New York with a message to deliver. While you were out....

*****

SI 60 Q&A with Alexander Wolff: No Michael Jordan? No problem

In a hype-saturated age, before a hype-inured crowd, in a building whose owners have enough chutzpah to call the place "the world's most famous arena," Jordan did more than live up to his extravagant billing that night. In his fifth game and 11th day back in the league, he somehow surpassed it. He did, indeed, go for 55 points against the Knicks--more than anyone had scored in the new Garden since it opened in 1968 and the highest total to that point in the NBA season. Dunking but once, he scored blithely, over and around six different members of a team notorious for its defense, until it came time to win the game. Then he did so with a pass.

With baseball still on strike, hockey scarcely off its lockout and football's most gifted and charismatic ballcarrier, its onetime MJ equivalent, being shuttled in handcuffs between a jail and a courtroom, the world of sports sorely craved what Jordan provided. But even he must have wondered if he was still capable of going off in such fashion--until three days earlier, in Atlanta. That's where he had fully reacquainted himself with the rhythms that in basketball come vertically, up from your feet, not horizontally, through your arms and hips, as a baseball player's do. Against the Hawks he had sunk 14 of 26 shots and scored 32 points, including the game-winning two on a hanging jumper at the horn. The performance sling-shot him on to New York, to find out, as the song says, if he could make it there.

On Tuesday the 28th, at the Bulls' game-day shootaround, the Garden is rank with the smell of elephants, the Ringling Bros. and Barnum & Bailey Circus having arrived five days earlier. But Jordan and a teammate, Ron Harper, are engaged in a game involving a different species: a version of H-O-R-S-E, half-court shots only.

"How much?" Harper asks, playing to Jordan's wagering jones.

"Fifty," says Jordan.

"I got you."

Three times they match each other, miss for miss, before Jordan bottoms one out. Then Harper launches his try into the air, and, amazingly, it too swishes through the hoop.

But here is what makes Jordan Jordan: His next shot, another 43-footer, is perfect. Harper is literally at a loss.

"Hah!" says Jordan, adding a sort of amen to an omen.

Every year the Super Bowl spends two weeks building itself up so 100 million Americans might be ritually let down. But there has been no fortnight of foreplay to Jordan's visit to the Garden, because two weeks ago he still was not officially under contract to play basketball.

As strobe lights and flashbulbs fire during warmups, the Garden is already full and charged with promise. Old hands, the ones who can recall the title fights of the Ali era and the Sinatra comeback concert held here, have a point of reference. But younger employees are thrown for a loop. "It was June all of a sudden, right in the middle of March," Chris Brienza, 30, the Knicks' director of public relations at the time, will say later. Brienza has issued credentials to some 325 members of the media (175 more than for a normal regular-season game) from a dozen countries. But only about half can be accommodated with seats, so an apology is distributed to every member of the press. "As you may have guessed," the handout begins, "tonight's Knicks-Bulls game is, shall we say, somewhat popular...."

Outside the Garden, the Bulls' team bus has taken 15 minutes to negotiate the half block from Seventh Avenue to the Garden's service entrance. Some people among the swells surrounding the arena bang on the sides of the motorcoach when they realize who's inside. Scalpers lucky enough to hold $95 lower box seats are getting as much as $1,000 a ticket. At Gerry Cosby & Co., the sporting-goods store in the Garden concourse, clerks are selling number 45 jerseys right out of the boxes. "All Bulls stuff is going again after being dead for a year and a half," says Cosby's Jim Root.

Jordan is normally available to the press until the locker room closes 45 minutes before tip-off. He particularly likes to engage the New York writers, to consider their smarter-than-average questions. But tonight he hides out in the training room, playing solitaire on his portable computer.

Every playoff renewal of the rivalry between the Bulls and the Knicks during the early 1990s has featured an incident with Jordan at its center. In '91, in Chicago's 103-94 Game 3 victory over New York, Jordan dunked over 7-foot Knick center Patrick Ewing as the Bulls swept the series. On the eve of Game 7 a year later, Michael asked for advice from his father, James, whose body would be found in a South Carolina creek 15 months later; Papa's counsel--"Take over"--worked just fine, with Michael going for 42 and the Bulls winning by 29.

In 1993 Jordan took his infamous gambling trip to Atlantic City between the series' first two games, both Chicago losses, yet he rose to block one of 6'10" forward Charles Smith's four unavailing shots under the basket as Game 5 wound down, and the Bulls eliminated the Knicks once more. Why, in Game 4 Jordan scored 54 points. (Imagine ... 54 points!)

The Bulls' route to each of their three crowns went through New York. Yet in 1994, with Jordan having been taken to task by a certain weekly sports magazine for "embarrassing" baseball, the Knicks finally beat Chicago and advanced to the NBA Finals. Thus, to New York fans, Jordan ought to seem like a Sisyphean rock. Yet there's affection in the voice of Mike Walczewski, the Garden's P.A. announcer, as he introduces Jordan, and unambivalent cheers from the crowd--a crowd that jeers the other Bull starters.

Jordan will later say that he had never felt less confident before a game. But the way he walks to the center circle for the tip-off, pausing halfway there to paw at the floor with his shoes like some ready-to-strike animal, hints at what is to come.

*****

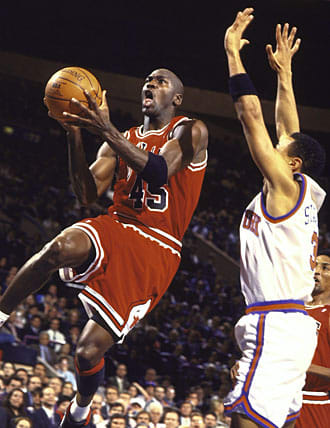

Much as he had done throughout the early '90s, Jordan picked on Knicks guard John Starks all night long.

Manny Millan/Sports Illustrated

How does a pro basketball player score 55 points? Even if you're Michael Jordan, it helps if you've essentially been ordered to do so by your coach. The request unburdens the conscience, leaving you free to let fly. For the better part of two seasons, Chicago coach Phil Jackson has run up against the skinflint New York defense too many times without Jordannot to take full advantage of his presence now. "They'd smothered us," Jackson will say. "We needed scoring. So I said, 'Go for it.'"

The first option of the Bulls' basic triangle set comes off the fast break. The team's most potent offensive threat nestles into the low post, hoping to get the ball there and make a move before the defense can entirely establish itself. During Jordan's absence, forward Scottie Pippen usually played this role, called post-up sprinter, but in Chicago's pregame meeting Jackson told Jordan to take up in the hub of the Chicago offense. "Everything else is pretty much a moot point if he can make his shots," Jackson will say afterward. "And we knew within a few minutes that he was making his shots."

His first, a short pull-up jumper in transition, comes on a pass from forward Toni Kukoc, the Croatian emigre who arrived after the Bulls' third title and had so looked forward to playing with Jordan that he broke down in tears the day Jordan announced his retirement. Jordan's second shot comes after he has set up as the post-up sprinter, and the Knicks are called for an illegal defense. He takes the subsequent inbounds pass and shows John Starks, who's attempting to guard him, a little mambo with the ball and a left-to-right rock before leaping up to shoot and score.

During the first quarter he'll do this again and again, having his way with the 6'5" Starks. Sometimes Jordan doesn't so much as show his face to Starks before spinning into a fallaway. The first time he feels Starks rest a forearm on his back Jordan spins past him and along the baseline for a layup. The next time he spins in the same direction, only to fall back and unspool another perfect jumper. Starks, with no recourse now, is whistled for a hold. As if to highlight the defensive quandary they're in, the Knicks are cited for their second illegal defense violation five minutes into the game.

Midway through the quarter, on consecutive baskets, Jordan knocks down two shots that are mirror images of one another: He takes two dribbles to his right, soars and feathers in a jumper (10 points now), then takes two dribbles to his left, leaps and sinks another (13 and counting). It's as if he's a basketball camper doing station drills, and the Knicks scarcely exist.

Here, finally, New York decides to dispatch some help to Starks. When Jordan next catches the ball on the low block, he finds Ewing rushing at him. Jordan spins to avoid the double team but, sealed off by the baseline, he's forced to leap up and throw a pass that's picked off.

In spite of this momentary success, the Knicks call off the double team. The move baffles Jackson, but New York coach Pat Riley has his reasons: In spite of Jordan's performance so far, the Knicks hold the lead and will for most of the game, at one point by as many as 14. And there's no team in basketball more adept than the Bulls at swinging the ball out of a double team and into the hands of an open shooter. "Their shooters and their spacing are so good," Riley will say, "that if you start running all over the place, they're going to get everything."

As the quarter winds down, Jordan seems joyous with each touch of the ball. One time he seems to bring his right knee up, in a sort of mummer's strut, as he rises into his shot (15 points now). "It's rare that players can live quite up to New York," Jackson, himself a former Knick, says later. "I've seen a lot of them fall flat on their faces because of the pressure to perform there. But he had the whole evening in the palm of his hand. Sometimes the game just seems to gravitate into his grasp."

At one point the Knicks throw a new jersey at him, 6'8" forward Anthony Bonner. Jordan has schooled the smaller Starks on the blocks; Gulliver here he takes outside, draining his longest jumper of the evening thus far, with a little leftward float thrown in to make it interesting (17 points). Then he bottoms out a three-pointer, only the second of 11 attempted treys to this point in his comeback (20 points). The Knicks lead at the quarter 34-31, but Jordan has sunk nine of 11 shots.

"I'm going to miss him," Starks had said upon hearing of Jordan's retirement. "He brought out the best in me."

"I think he forgot how to play me," Jordan will say after the game.

*****

So many celebrities are in the Garden that if the Oscars hadn't taken place in Los Angeles the night before, the whole country might be listing alarmingly to starboard. The usual potted plants, Knick regulars Woody Allen and Spike Lee, are rustling their leaves courtside. Tom Brokaw, Peter Falk, Bill Murray, Diane Sawyer and Damon Wayans all have taken the trouble to rearrange their busy schedules. There's Christopher Reeve, pre-accident, and Mario Cuomo, post-Pataki. And tonight the stars seem to come in pairs. Phil and Marlo. Connie and Maury. Lawrence Taylor and fellow pro wrestler Diesel. Even pairs that should be together: Itzhak Perlman, recording artist, and Earl (the Pearl) Monroe, now a recording executive.

As Jordan goes for the speed limit, announcer Al Trautwig, working the sidelines for MSG Network, approaches a large man sitting courtside. "Excuse me," he asks. "Are you Al Cowlings?"

In spite of having its own financial market and international flights to 65 cities, Chicago has a woeful dearth of celebrities. Joe Mantegna and Oprah can only take a town so far. Chicago is so star-poor that, months later on Monday Night Football, a Bear fan diving 30 feet from the stands in pursuit of an extra point will end up with the same agent as Jim McMahon.

Thus the city must get all it can out of its single world-class celeb. Two nights after Jordan's New York epic, SportsChannel Chicago will air 24 hours of highlights and documentary footage of, and interviews with, the man himself. And a Windy City radio station will poll its listeners on the pressing matter of whether Jordan should be named King of the Universe.

It's a wonder that only 41% say yes.

*****

SI 60: 'Lawdy, Lawdy, He's Great'

In the second quarter Jordan seems to slip the bounds of the Garden and reinvent his surroundings--to pull asphalt under his feet and the spirit of New York's playgrounds into his bloodstream. Fifteen of the Bulls' 19 points this quarter will be his: his 28th and 29th of the game on his staple, the simple fallaway over Starks; his 30th and 31st after jabbing with each shoulder, then spinning into another fallaway that beats a dying shot clock. In a glimpse of foreshadowing, up for a jumper near the end of the half, he passes up the shot, pitching instead to a 7-foot teammate, end-of-the-bencher Bill Wennington, who pitches it right back.

Jordan's tongue comes out often as he makes these moves, of course. But at one point he flashes a trace of a smile. His mirth is evidently contagious; later in the game Starks will head downcourt unable to suppress a laugh at the ridiculousness of what he has become a victim of. "In a game like this," the former supermarket checkout clerk says later, "you just have to hope he starts missing."

Jordan hardly has missed as he leaves the court at the half. The Bulls trail 56-50, but Jordan has sunk 14 of 19 shots. As he files through the tunnel an adolescent girl reaches over the railing above, risking getting singed as Jordan's hand meets hers.

A Garden basketball crowd is famous for its ability to make the syllables of the word defense sound like invective. Yet Jordan and his 35 points have reduced 19,763 people to disorganized murmuring. Going back nearly four decades New Yorkers have been quick to root for the home team, but they've also been appreciative of the great opponent. The Knicks sucked rotten eggs during the early 1960s, but the undercard of an NBA doubleheader back then might have featured the Boston Celtics or the Philadelphia Warriors, and fans would fill the old Garden for a 6 p.m. tip-off to behold the conjurings of a Cousy or the majesty of a Chamberlain.

Yet through the 1990s Jordan haunted the Garden in part because some of that connoisseurship seemed to spill from the loges and infect the Knicks themselves. From power forward Charles Oakley, the team's enforcer and an ex-Bull who adores his former teammate, to Starks and that laugh he'll let slip, the entire Knick family seems to have a streak of the fan in it.

Not that anyone in the stands is going to take the Knicks to task for falling under Jordan's spell, least of all tonight, anyway; they too are his hostages, suffering from a sort of Stockholm syndrome. "More than anything else, the fans wanted to see him have a great game," Jackson will say. "It was like they'd gone to a Broadway show."

*****

Intermission over, Jordan scores points 40, 41 and 42 on a three-point shot. Forty-seven, 48 and 49 come on another trey. No one in the NBA should be able to jump-shoot his way to a total like this, least of all against a team of bogarters like the Knicks, least of all Jordan, whose J is a jumble of knocked knees and limbs akimbo even when it's clicking, and it hasn't been clicking since he returned. Yet here he is, on his way to scoring 55 the way Larry Bird might have scored 55.

The Bulls' Steve Kerr may be the best three-point shooter in the league. Yet friends will tell him later that he looks starstruck as he sits on the bench, watching as Jordan sends shot after shot whispering through the net. The reaction of players like Kerr worries Jackson. The Bulls were so dependent on Jordan prior to Jackson's taking over the team in 1989 that then assistant coach John Bach referred to the team's "archangel offense." To transform Chicago into the group that won three straight titles, Jackson took on twin missions: to jawboneJordan into involving his teammates more through the triangle offense, and to persuade the "Jordanaires" that the team's goals weren't being served if they stood around gawking during number 23's levitations. Jackson's membership on the 1973 Knick title team, a squad founded on balanced scoring and a commitment to finding the open man, established his bona fides as he made that sale.

At first Jackson and Jordan coexisted in delicate balance--the coach with his higher truth of championship basketball, which Jordan so desperately sought; the superstar with his worldly gift, the ability to manufacture baskets when Jackson's beloved triangle broke down. By the time the Bulls won their first crown, Jordan had become so committed to team play that he accepted the ritual "I'm going to Disney World" endorsement opportunity only when the other Bull starters were included. Yet now Jackson wondered if he would have to make both pitches all over again. No one on the team had played with Jordan before his return other than Pippen, center Will Perdue, swingman Pete Myers and guard B.J. Armstrong, who as a rookie had actually checked out a library book on Einstein and Mozart, hoping they would give him insight into genius and make him a more sympathetic teammate to the great one. And would Jordan come to understand that the team, which had been playing well when he rejoined it, didn't need a savior?

As if to provide Jackson with Exhibit A in that case, Chicago seizes its largest lead, 99-90, precisely when Jordan is taking his longest rest of the evening, for more than five minutes at the start of the fourth quarter. The Bulls knew they could score by letting Jordan go one-on-one. Now they have proved they can prosper without him at all.

Still, Jackson might wonder: Can the team click with Jordan a constituent part?

*****

SI 60: 1954-94: How We Got Here Chapter 1: The Titan of Television

As the game enters its final minutes Jordan and Ewing are taking turns. Another Jordan jumper over Starks--points 52 and 53--gives the Bulls a 107-102 lead. After Starks counters with two free throws, Ewing adds one of his own; then, finally coming over again to help Starks on a double team, he blocks a Jordan shot, making possible a slam from Starks that ties matters at 107. Jordan dishes off for his first assist of the game, to Pippen for a bank shot, and Chicago leads 109-107. Ewing's two free throws reknot things at 109 with 39 seconds left on the clock.

It's felicitous that Jordan and Ewing, Ewing and Jordan, are engaging each other down the stretch. In a few months they will be leading an uprising against the players' union. At the Plaza earlier this afternoon Jordan met with Charles Grantham, at the time the executive director of the players' association, to bone up on issues pertaining to a new collective bargaining agreement. By tonight's lights, could there be any better pair to make the case for how very productive NBA labor can be?

*****

At Turner Broadcasting in Atlanta the suits know that the Nielsen ratings took their usual dip at halftime. But they spike up with the start of the third quarter, the result of tens of thousands of Hey, are you watching this? phone calls. Through the final two quarters the numbers creep upward in 15-minute increments, from a 5.2 to a 6.0 to a 6.8 to a 7.4 to an 8.0, ultimately averaging a 5.0 rating--a record for a nationally telecast game on cable.

Steve Smith of the Hawks yapped at Jordan three nights earlier, proving anew that, all things considered, mouthing at Michael isn't a prudent thing to do. "Who's going to get the shot?" Smith asked Jordan as the Bulls prepared to put the ball in play for the last time.

"Pippen," Jordan said, before taking the inbounds pass with 5.9 seconds to play, moving up the floor and beating his interlocutor with the game-winner.

Tonight, as adrenaline gets the better of Starks, he can't help himself. "Hey, how ya doin'?" the Knick guard asks Jordan late in the game, renewing acquaintances, after a fashion. "What's been goin' on?"

The same free-flowing juices that set off Starks's mouth cause him to bite for any fake Jordan offers, including this one. Starks is on his way down, helpless, as Jordan rises up for his final attempt, and final basket, of the night. The score now stands at 111-109, Chicago.

Jordan has squeezed off 37 shots. Twenty-one have found their mark, three from beyond the arc. Throw in his 10 foul shots and Jordan, as Spike Lee will put it, has dropped "a double nickel" on the Knicks.

*****

During the 1994-95 season, Chicago's second-most celebrated basketball player may have been a West Sider named William Gates. He's the costar of Hoop Dreams, the acclaimed documentary film that traces Gates's life from age 14, when he was only a whisper in the Cabrini-Green housing projects, through high school, to the day his world-weary mother and washed-up older brother tearfully send him off to Marquette on a full scholarship. In a moment that gets just right the suddenness with which parenthood can steal up on adolescents living in places like Cabrini-Green, the film cuts to a shot at the Gates's kitchen table. Encircling it are an infant girl, Alicia; her teenage mother, Catherine; and William, who, it becomes quickly clear, is Alicia's father. They are discussing the day Alicia was born and Catherine's request that William be in the delivery room?a request that went unfulfilled. "I can't miss a game just because an incident occurs, you know, unless it was like a death or something like that," William says.

"Something like that!" says Catherine. "This is a once-in-a-lifetime thing! Like the girl is born every day...."

"Especially around that time of the year, too, state tournament," says William.

Last night, Oscar night, Gates was in the Garden, playing in the Golden Eagles' 87-79 NIT semifinal defeat of Penn State. Gates didn't intend to let the Bulls pass through town tonight without looking in on his homeboys, and, a movie star now, he lined up courtside seats with Lee. But at 6 a.m. Catherine, now Gates's wife, called to tell him she was again going into labor, more than five weeks early.

It's an instructive epilogue to the film that Gates headed back to Chicago to witness the birth of his second child, William Jr. "Catherine's getting me back," Gates thought to himself as he headed for the airport. "Michael saved that performance for me, and I missed it," he will say upon hearing what had occurred in his absence.

Gates never did make it back for the NIT final, which Marquette lost 65-64 in overtime to Virginia Tech. Yet his decision bespoke a maturity that developed only after Hoop Dreams finished filming. He seems to have learned that you can hoop-dream all you want, but ultimately reality will settle back in--and in reality there's much more to life than a basketball game.

*****

SI 60: 1954-94: How We Got Here Chapter 1: The Titan of Television

The foul that puts Starks on the line, where his free throws will tie the game at 111, is Perdue's sixth. Jackson sends Wennington in at center, and the Bulls call a timeout.

In the huddle the Bull staff points out that the Knicks have permanently changed their defensive thinking. After letting Starks (and such others as Greg Anthony, Hubert Davis and Derek Harper) be used and abused for most of the game, New York has sent Ewing over the last three times Jordan probed the Knick defense. Jackson and his aides remind Jordan that there will be a vacuum in the middle into which a teammate might slip.

Jordan dribbles to precisely the same spot from which he sank his last shot, the right elbow of the foul lane. Starks tracks him all the way. Sure enough, Ewing rushes over. "I'd be lying if I said I was coming out to pass the ball," Jordan will say later. "I was coming out to score. But then Patrick came over to help...."

It's an article of basketball faith that a player who's double-teamed finds the open man. But Jordan has been so individually mesmerizing to this point that his pass to Wennington, who looks like a leper alone under the basket, seems like a revelation.

From Jackson's vantage point it looks as if Jordan has pulled an Amazing Kreskin, bending his pass around the onrushing Ewing. Starks has been so fooled by Jordan's sudden pass that, after biting on another fake, he stumbles, spraining his left ankle. From the Garden floor Starks's view must have been obscured; following the game he believes Perdue has scored the dunk that wins the game 113-111.

Before the Bulls strung together their three titles, critics returned again and again to three quibbles with Jordan: That for all his individual greatness, he wasn't a winner; that his heedless defensive wanderings left the rest of the Bulls vulnerable; and that when he was double- and triple-teamed, he couldn't reliably find his teammates. Not that he needs to, but within a few seconds Jordan provides a tidy set of refutations, one for each canard: The Bulls win. When Starks fumbles away New York's last chance in the final three seconds, it is under pressure from Jordan. And the winning shot comes on Jordan's pass.

To Jackson, a son of Pentecostal ministers and a relentless proselytizer for team play, that last act is the night's transcendent moment. "Justice," Jackson says of that pass. "Poetic justice. It brought reality and order back to the evening."

No longer able to dictate to their lavishly paid charges, NBA coaches are all social workers now. The best ones have found ways to reach their players almost subcutaneously. Jackson's style of management is particularly indirect. As he explains in his new book, Sacred Hoops: Spiritual Lessons of a Hardwood Warrior, Jackson prods and pokes, trying less to drum into each Bull a set of cold facts than to nudge him to a heightened state of awareness. As a result players often come to Jackson after they've realized what he wants them to grasp.

Several days after the Knick game Jordan approached Jackson. "I've decided to quit," he said. "What else can I do?" Jordan was kidding. But he soon became serious. Jackson had encouraged him to fire away that Tuesday night. But Jordan told Jackson that he understood how his outburst in the Garden had to be an aberration if this fragile and reconstituted team were to challenge for the title. "You've got to tell the players they can't expect me to do what I did in New York every night," Jordan said. "In our next game I want them to play as a team."

As glad as Jackson was to hear Jordan say that, things wouldn't be so easy. The whoopee over his return cleaved Jordan from his teammates. As he searched for privacy, Jordancocooned himself inside his retinue of friends and followers--a natural and perhaps necessary reaction, but one that alienated him from the group. The confidence and trust the team had developed before Jordan's return began to dissipate. Nowhere was this more evident than in two games in the Eastern Conference semifinals against the Orlando Magic. Rust and unfamiliarity with his teammates led Jordan to bollix up critical plays late in Games 1 and 6.

To reemphasize to Jordan and Jordanaires alike their interconnectedness during those ill-fated playoffs, Jackson had read the team a favorite passage of his from Rudyard Kipling. It's a text Jackson is sure to return to this season, as the Bulls make another run for a title, this time while integrating into the team the iconoclastic personality of Dennis Rodman.

Now this is the Law of the Jungle--

as old and as true as the sky;

And the Wolf that shall keep it may prosper,

but the Wolf that shall break it must die.

As the creeper that girdles the tree trunk,

the Law runneth forward and back--

For the strength of the Pack is the Wolf, and the strength of the Wolf is the Pack.

Basketball's great wolf had his howl on that Tuesday night in the Garden. But having delivered a message, he was ready to return to the game's ultimate truth, a lesson his coach regards as holy writ: That if you're not in it together, you're not in it to win it. And if you're not in it to win it, double nickels ain't nothing but chump change.