If Alexander Volkov is not the first NBA alumnus to serve in a war, he is unquestionably the oldest. He was a few weeks shy of turning 58 when he put away his business suit and squeezed his 6'10" frame into head-to-toe camo. Ukraine had just been invaded by Russia, and, without hesitation, the former Atlanta Hawk volunteered to defend his homeland.

He met with a local militia-type group to distribute weapons and organize makeshift training drills. He helped arrange for trailers filled with humanitarian aid to arrive from neighboring countries. He went on night watch, folding his body into his Volkswagen Touareg and driving around his village outside of Kyiv, “patrolling for looters and saboteurs.” This sure as hell wasn’t the way Volkov—a grandfather, a sports minister and a 2020 FIBA Hall of Fame inductee—envisioned spending his nights. But, as he puts it, “Yes, war is a desperate time.”

Rocky Widner/NBAE/Getty Images (Volkov); Scott Cunningham/NBAE/Getty Images; Courtesy of Sarunas Marciulonis (kids)

A few days in, Volkov got a sense of just how desperate when he learned that his boyhood home in Chernihiv, about 100 miles north of Kyiv and in the path of the Russian advance from Belarus, had been bombed. The third-floor apartment that he inherited from his parents and was renting to a family was reduced to smithereens. He shared photos of the rubble and captioned them, “I know every inch of this backyard” and added: “My aunt was [there] during this. Thank God she survived.”

For much of March, his days were interrupted by the sounds of bombs and helicopters and air-raid sirens, each bringing a surge of adrenaline. He heard explosions and could only hope it was the Ukrainian anti-aircraft missiles doing their job. He slept little, worried lots and, like so many Ukrainians, scrolled through his phone for the latest text messages and reports on Telegram. His emotions toggled from disbelief to fear to rage.

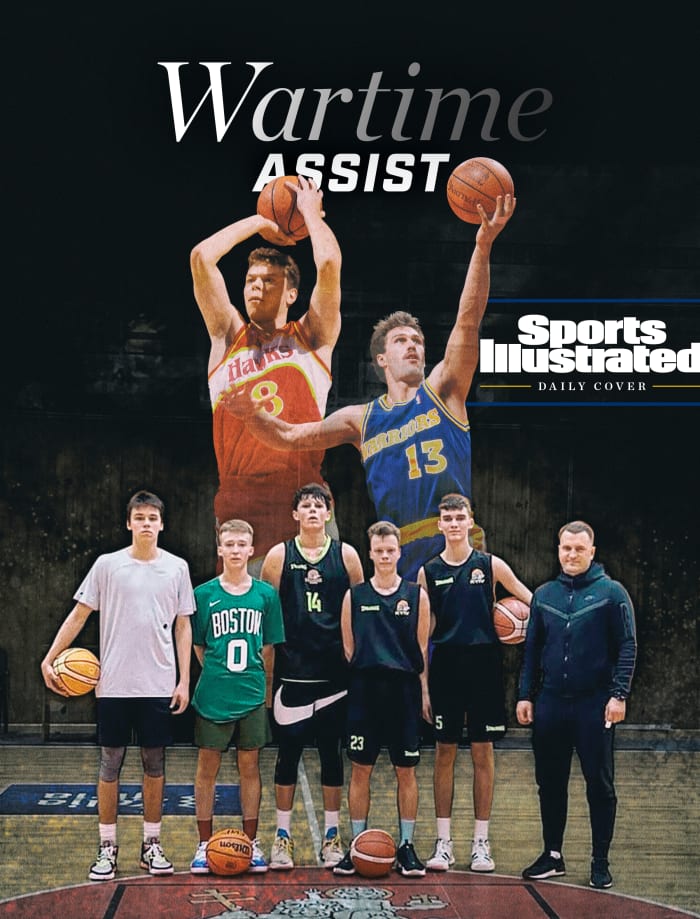

Mostly, though, since the beginning of the war, he has been concerned for his kids. Not his two daughters, who are safely living outside the war zone, one in New York and another in Atlanta, but for his basketball players. Since leaving the NBA and returning to Kyiv in the 1990s, Volkov has funded a youth basketball academy filled with about 90 Ukrainian kids and teenagers with ambitions of playing college and professional ball. With the country under attack, danger lurked everywhere. Troops were advancing toward Kyiv. Bombs were detonating in malls. The kids were too old to be oblivious and too young to serve in the Ukrainian army.

One of his first calls after the invasion began was to one of his oldest friends, a longtime former teammate now living in Lithuania. Says Volkov, “It was simple. I ask, ‘Šarūnas, can you help me?’”

Volkov's childhood home suffered heavy damage in a Russian bombing attack.

Courtesy of Alexander Volkov

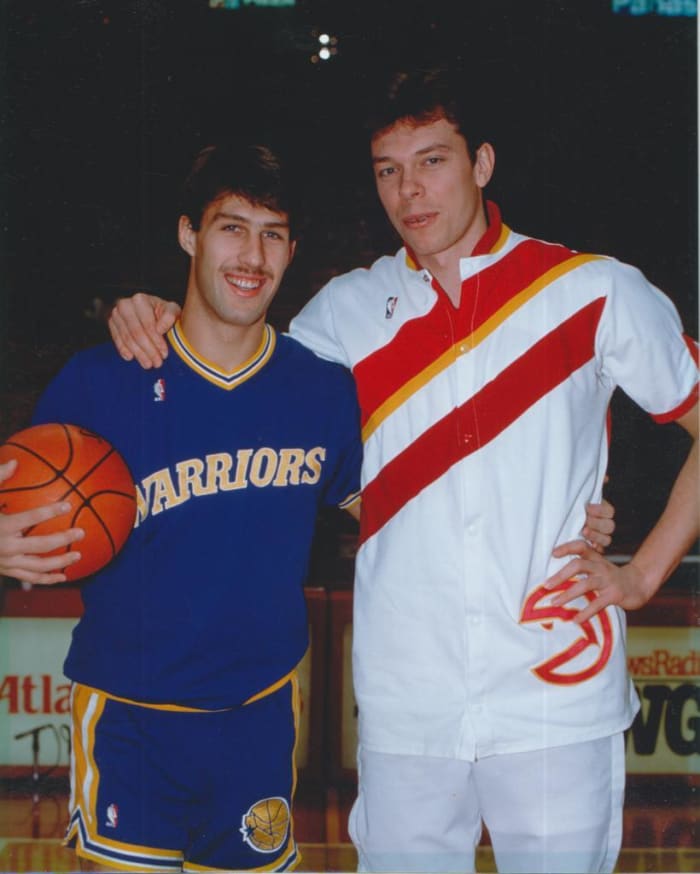

Šarūnas Marčiulionis refers to Alexander Volkov as “Volciokas.” It translates roughly to Little Wolf, and it’s an inside joke, the kind you make with someone you’ve known for 40 years. Neither of them can believe the escape velocity of time, but it was the early 1980s when Marčiulionis and Volkov, then teenagers, were roommates at basketball camp. Volkov came from Ukraine. Marčiulionis came from Lithuania. And they were stalwarts in the Soviet system.

Marčiulionis was a shooting guard, compactly built, who deployed what we now would call the Eurostep. He hesitated, then lowered his head and charged toward the basket at every chance. Volkov was a power forward who would eventually grow to 6'10". Coaches encouraged him to play with his back to the basket, but he preferred to face up, bringing to bear his soft touch, surprisingly nimble footwork and court vision.

Their basketball journeys would wend and wind in directions inconceivable to the Soviet teenagers, sometimes intersecting, sometimes diverging sharply and often tracing geopolitical arcs. Marčiulionis and Volkov were teammates on the 1988 Soviet Olympic team that beat the team of U.S. college players and won gold in Seoul. They joke that they helped give birth to the Dream Team. “After those Olympics,” says Marčiulionis in his rumbling voice, “there was no way America wasn’t going to let the pros play.”

In the 1992 Barcelona Games, the U.S. won gold, but Marčiulionis played a scene-stealing role. His country had recently declared independence from the Soviet Union, and the tie-dye-clad Lithuanians were the darlings of the basketball event. Marčiulionis was the expressive perimeter player. Stoic and mystical Arvydas Sabonis was the force down low. “The Other Dream Team” enthralled crowds, charmed Michael Jordan and Magic Johnson and Larry Bird, and marched to the medal round. In a game dripping, equally, with significance and symbolism, the Lithuanian team beat Volkov and his unified squad of 12 former Soviet states—including Russia— 82–78, to win bronze. “In terms of importance, yeah, the biggest game of my career,” says Marčiulionis. “It’s amazing the energy that comes from playing for a new country, a country trying to prove itself, show an identity, you know?”

By then, both Marčiulionis and Volkov were in the NBA, having entered in 1989, part of a small wave of Eastern Europeans that also included Dražen Petrović and Vlade Divac. Volkov headed to Atlanta and played for the Hawks, a team owned by Ted Turner, who, not coincidentally, staged the Goodwill Games and had significant sports ties within Russia. Marčiulionis started off with the Golden State Warriors. Today, of course, international players populate much of the NBA, and, for the fourth year in a row, the MVP will have been born outside the U.S. In the late ’80s, Volkov and Marčiulionis, though, were blazing trails. Volkov was celebrated at the time as “the first Russian to make the NBA.”

Today, Marčiulionis, 57, lives in Vilnius, the Lithuanian capital, where he returned after his eight-year NBA career and tends to various businesses—and, he says, tries to stay in shape, while putting on a sport coat as seldom as possible. Volkov still lives in Kyiv, his home since 1995 after retiring from his pro basketball career, which included three NBA seasons and 11 more across Europe. Since then, Volkov has come out of retirement to play for the Ukrainian national team; founded and served as president of the pro team BC Kyiv; had a stint in the Ukrainian parliament; and launched the basketball academy. Life, he says, was good. Until it wasn’t.

When the Russian invasion began on Feb. 24, Volkov was ready to resist—but he also wanted to help others reach safety. When he called his buddy, his voice edged in urgency, asking for help, Marčiulionis didn’t even need to hear the rest of the sentence.

“Of course,” Marčiulionis recalls responding. “What can I do?”

Volkov explained the situation. This group of players, all born in 2006, needed to get the hell out of harm’s way. Could Marčiulionis take care of them?

Marčiulionis agreed without hesitation. So those nine 15- and 16-year-old Ukrainian basketball players—roughly the same age Marčiulionis and Volkov were when they first met—piled into cars headed for Vilnius. Some were accompanied by their mothers; others hugged their parents goodbye, unsure when they’d next meet. They left Ukraine, drove through Poland and entered Lithuania. Marčiulionis was there to greet these new refugees.

Like Volkov, Marčiulionis is involved in a youth basketball academy. He set up housing for the new arrivals to Lithuania. He is trying to enroll them in local schools. He’s encouraging them to use basketball as an outlet, time on the court as an interval where they escape the trauma of war and “find a [sliver] of normal.” He has also helped connect the kids with his teammates in other communities, including Sabonis, who now lives in Kaunas, Lithuania.

Volkov’s full network of basketball connections has been eager to help as he’s tried to find landing spots for his charges. Take, for instance, the story of Semen Plachkov, a 6'3" 15-year-old shooting guard from Kyiv determined to model his game after his NBA hero, Tyler Herro. “My dad was volunteering [to help the Ukrainian defense],” he recalls. “We are thinking my mom [and I] should be safe.”

After some brokering from Volkov, Plachkov, his two siblings and mother left Ukraine for Lithuania. They had designs of going to Vilnius, where Marčiulionis and some of his other teammates were waiting. Instead, they were connected to the Tornado Basketball Club in Kaunas, which has ties to Sabonis. On March 3, Plachkov, his mother and brother caught a ride to Warsaw. What would otherwise be a 10-hour drive ended up being a five-day odyssey. In Warsaw, they were met by a Lithuanian basketball go-between who drove the family five hours to Kaunas. “They gave us food and a flat to live in and a place on the team,” says Plachkov.

Three of Plachkov’s teammates from Kyiv ended up joining him in Kaunas. They attend ninth grade together at a local city school, get daily tutoring in Lithuanian and play on the same team. “I like the coach. I like the gym. The basketball level is very high. I like everything here. For all things [considered], it’s pretty great.”

Says Volkov: “I never saw this was going to be such big support. I receive phone calls from all over the world. I never received so many calls in my life with some friends [some] I really didn't talk to for like 20, 30 years. They called me and offer any support they can. … And you cannot imagine how many kids send me an appreciation, appreciation messages and parents, also.”

Of his friend, he adds, “Šarūnas did such a great thing. Such hospitality.”

Marčiulionis (no. 7) helped lead the Soviet team to Olympic gold in 1988.

John W. McDonough/Sports Illustrated

Marčiulionis’s open arms are in keeping with his organizing principles. Philanthropy through sport has always figured prominently in his story. In the 1980s, Marčiulionis met Donnie Nelson when the latter played on an Athletes in Action touring team. They overcame their language barrier and struck up a friendship; Nelson sized up Marčiulionis, a 6'5" bull, as a future NBA player. Two years later, Marčiulionis was in Lithuania playing in a tournament when a man desperately approached him and explained that his teenage son was suffering from a rare heart condition and that only an artificial valve could save the boy.

Here is how Sports Illustrated’s Alex Wolff put it in a rich 1992 profile of Marčiulionis titled “I Have to Open People’s Eyes”: “Marčiulionis did the only thing he could: He appealed to his new American friend. Donn canvassed the States, trying vainly to acquire an artificial valve. Finally, with the help of Nelson’s mother, Sharon, and the congregation at her Milwaukee church, Marčiulionis and Donn were able to bring the boy to the U.S. and introduce him to Dr. Jim King, a heart specialist, who performed the operation.”

When Marčiulionis came to the NBA in 1989, not surprisingly, he ended up with the Warriors, a team coached at the time by Donnie Nelson’s father, Don. It was a good fit in more ways than one. Nelson’s uptempo offense suited Marčiulionis, who would play on the Run TMC team, the fourth scoring option after T (Tim Hardaway), M (Mitch Richmond) and C (Chris Mullin). He would involve himself in various acts of benevolence, both in the Bay Area and at home. (When Wolff visited, Marčiulionis was trying to counter the economic effects of Lithuania’s breakup with the Soviet Union by funding a boarding school for blind children.)

Marčiulionis downplays any suggestion that has done anything remotely extraordinary recently in helping Volkov. Vilnius is less than 30 miles from the border of Belarus and sits between Russia and the critically strategic Baltic port of Kaliningrad. In Lithuania, there is not only fierce support for Ukraine but a sense of we could be next. If anything, Marčiulionis wishes he could do more. “It’s nine kids in two rooms, not glamorous,” he says. “But we’re getting them in school. We’re getting [their mothers] settled. It’s not an ideal situation, but it’s better, obviously, than where they were.”

Sitting inside Stars and Legends, the sports bar he owns in downtown Vilnius, Marčiulionis would rather steer the conversation to happier topics. There’s padel, a tennis-like game that is his new sports obsession. There’s the resort community he is developing—50 residential units with a hotel to come—on a lake between Vilnius and the Baltic Sea. He is happy to introduce an acquaintance to his wife, Laura, whom he married in 2012. Marčiulionis’s son, Augustus, plays point guard for St. Mary’s in California, and while the 10-hour time difference is a killer, Marčiulionis will arrive early and watch his son’s games from the previous night.

But Volkov, speaking over the phone, would prefer we linger a bit longer on Marčiulionis’s good deeds. Volkov is out of Ukraine now, having driven out of the country in early April with his wife, heading through the Ukrainian city of Odesa and Moldova and arriving in Istanbul, where he met with FIBA executives, in part to get assurances that all his young players scattered throughout Eastern Europe will get to retain Ukrainian basketball status when this damn war finally ends. The Volkovs then got on a flight to Atlanta on April 6 to be with their daughter and grandson. “At the airport, you can’t believe how much crying there was.”

Volkov’s voice catches as well when he reflects on his old friend. They came up through the Soviet system together, are now filled with disgust toward Vladimir Putin’s Russia and are carrying out a sort of resistance through sports.

“He’s always been like my brother, and I’ve always been very close to him. We share the same philosophy, same values throughout all life. And still now.”

Read more of SI’s Daily Cover stories here:

• How Russia Pushed the WNBA to a Crossroads

• Sportswashing Is Everywhere, but It’s Not New

• Why the Sports World Doesn’t Miss Russia