Chris Mortensen’s Cancer Battle

Video: Tiff Oshinsky

This is one in a series of stories from The MMQB about people in and around the NFL who have been affected by cancer.

BRISTOL, Conn. — “What,” Chris Mortensen is asked, “was a dark moment for you?”

He might have said it was when a doctor told him, matter-of-factly, in January 2016 that he suspected Mortensen had the most severe and advanced form of malignant throat cancer. Not good for anybody; especially bad for someone whose voice is his living. He might have said when he told his wife, Micki, the diagnosis, and she crumpled to their floor, sobbing, and then ran outside screaming, “Oh God! Oh God!”

But there was something worse. It was about seven months into Mortensen’s treatment, when he wanted to be euphoric, because the last of 35 debilitating radiation treatments, designed to burn away the tumor in his throat, was over. Now maybe he’d finally start the feel like the old Mort, life-of-the-party Mort, needling-Chris Berman-on-the-set-of-“Sunday Countdown” Mort.

No. Doctors told him to prepare to feel his throat cooking for the next one to two months.

“That’s exactly the phrase they used,” Mortensen said. “‘You’re still cooking.’ They said, ‘You’re still cooking for four, six, eight weeks after you’re done [with radiation treatments].’”

Reporter that he is, Mortensen sounded surprisingly matter-of-fact talking about his outlook during the days, and weeks, when his throat felt like it was on fire.

“I wondered, you know … whether I’d finish out the year.”

Mortensen finished out the year. He is on course to finish out this one. Statistics in cancer are ever-changing because of the advances in the science surrounding the disease, but the survival rate for the form Mortensen had, oropharyngeal cancer, at the stage it was, is about 40 percent. Mortensen’s throat and tongue are clear now, but the cancer has spread to his left lung, where last November doctors found several malignant nodules. More treatment, this time with an IV regimen every three weeks; last week he had his 15th treatment. “I’ve asked how long this will go on, and they say maybe forever,” said Mortensen, 65. “They have to make sure it doesn’t metastasize to anywhere else. Right now, it’s metastasized to my lungs.”

That is the new normal for Mortensen: doctors chasing this insidious disease inside him. It might be this way for the rest of his years.

This is why Mortensen does not like the phrase “beat cancer.” He hasn’t. There he is, looking 85 percent of his old self on TV, and you think, Glad he beat it. “One thing people need to know—Chris still has cancer!” his wife, Micki, emailed just this week.

Mortensen is ahead by a touchdown at the end of the first quarter, is where he is.

We’ll get to the now soon. The then part of Mortensen’s sporting life is pretty cool. Chris Mortensen once covered a high school baseball all-star game in El Segundo, Calif., where Robin Yount played short, George Brett played third, and Brett pitched the last inning of the game throwing from both sides. He retired the first two batters throwing right-handed, and then, when a lefty hitter came up, they brought him a different mitt. Pitching lefty, Brett faced a left-handed hitter. “He fielded a little topped bouncer to the third-base side of the mound and fired it to first left-handed for the third out,” Mortensen recalled. “Blew me away.”

Mortensen loved baseball, growing up in Torrance, Calif., and listening to Vin Scully call games. He graduated to the Dodgers beat at his hometown paper, the South Bay Daily Breeze, traveling the country and covering the Garvey-Cey-Lasorda team while in his 20s. What a time to be a sportswriter. He covered the fifth of Nolan Ryan’s seven no-hitters, at the Astrodome in 1981, when Ryan struck out 14 Dodgers. Just this Tuesday night he was watching Game 1 of the World Series, and the Fox cameras cut to Vin Scully, and then to Sandy Koufax, and it got him to thinking about his former life. “I can see Sandy Koufax to my left in the Vero Beach Dodgertown lounge a few feet from our media work area, having a cold draft beer,” Mortensen said, “and me shaking my head like, Am I really living this?” He covered the NFL in Atlanta and then at Frank Deford’s The National before arriving at ESPN in 1991. Will McDonough was the first major long-term newspaper-turned-TV NFL insider. Mortensen was the second, and a powerful one. The NFL stories he’s broken … Warren Sapp failing drug tests in college, pushing his stock down on the eve of the 1995 draft … The Chargers, after going 14-2 in 2006, shockingly firing coach Marty Schottenheimer … Confirming the under-inflation of Patriots footballs in the Deflategate affair in 2015 (more about that later) … Peyton Manning retiring in 2016.

Manning’s retirement—there’s a story. A preamble first. Mortensen announced on Jan. 15, 2016, that he was taking a leave of absence to begin treatment for stage four throat cancer. The outpouring of well-wishes from his co-workers and the media was immense. The league reaction, perhaps more so. One night after the announcement, in an NFC Wild Card game, Arizona’s Larry Fitzgerald caught an overtime touchdown pass to lift the Cardinals over Green Bay. Moments after celebrating on the field, Fitzgerald was grabbed for a postgame interview by ESPN. Still out of breath, Fitzgerald looked into the camera and said: “Mort, I wanna tell you, we’re thinking about you. And fight, baby. Love you Mort.”

It still strikes a chord with Fitzgerald now. “Honestly, I was overcome with emotion at the time, just thinking about it, even right after the game,” Fitzgerald said last week. “It just came to my mind. Mort’s so much a part of this league, and when he came out with it, he was so open, so public. Unfortunately I know the plight, having lost my mother to breast cancer, so I’m a lot more aware. I had to say something.”

Mortensen went off the radar. Five days after his announcement, he began treatment at the MD Anderson Cancer Center in Houston. For six months he was pummeled with chemotherapy, then radiation. Micki was his lifeline in Houston. He’d answer texts occasionally, and sometimes talk on the phone to son Alex, who is on Nick Saban’s coaching staff at Alabama, and with friends. He looked down at his phone one Saturday in March, when he felt like crap. Peyton Manning.

He and Mortensen are close. Very close. Each summer Mortensen was a regular at the Manning Passing Academy in Louisiana, not as a reporter, but as an observer and friend, hanging around, riding a golf cart with Archie Manning to watch the fledgling quarterbacks go through drills, with brothers Peyton, Eli and Cooper running the show. When Mortensen went public with his battle, he got an email from Archie each morning—a daily devotional, an inspirational Bible verse. “I had to do something,” Archie said. “That news hit me like a sledgehammer.”

Mortensen wasn’t answering his phone much in those days, but he picked up this time.

“I’m just calling a few people,” Peyton Manning said, “to tell them I’m retiring. I’m going to do it Monday in Denver. I wanted to let you now.”

Pause.

“Do you want to report it?” Manning asked.

“I think I would,” Mortensen said. “It’d make me feel normal again.”

“Can you do me a favor?” Manning said. “Can you give me one last night as an NFL quarterback, to go out to dinner with family and friends? Can you hold it?”

Mortensen agreed to hold it until Sunday. He and the news desk at ESPN prepared a written story that would post the next morning. His boss on the football show, Seth Markman, was petrified they’d get beaten on the story. Somebody’s gonna tell somebody! Mortensen was resolute: no leaks. Nothing until Sunday morning. “It’s not even a discussion,” Mortensen said. “I gave my word. We’re sitting on it. If someone else breaks it, so be it.”

Mortensen was a fixture at the Manning Passing Academy. When he couldn’t make it in 2016, Archie had supportive wristbands distributed to all the campers.

Courtesy Chris Mortensen

“It drove me crazy,” Markman said last week. “I kept thinking maybe I could call Adam [Schefter] and say, ‘Maybe you could make some phone calls on Manning,’ and if he found out independently, maybe … But I just couldn’t do that. Instead, I went to bed that night, scared to death. I put my computer on my nightstand. I would wake up every hour and check it—did anyone have the Manning story? There are times you throw your journalism degree away. This was one of them.”

The story survived. Mortensen broke it just after dawn Sunday.

“I wanted to call all the people who’ve been a big part of my football life,’’ Manning said this week. “My head coaches—Jim Mora through Gary Kubiak. Some assistant coaches. Some coaches I competed against—Bill Parcells, Bill Belichick, Andy Reid. Teammates. And Mort. He’s been a part of my football life. Some of them I couldn’t reach, so I texted. What was amazing, when you really think about it, is not a single one of them of them said anything. So I guess you would add Mort to the list of people in the game I really trusted.”

Sometimes you don’t know what you’re missing until it’s gone. Mortensen pulled himself from the ESPN lineup during the playoffs in January 2016. His little TV brother, Schefter, was morose. “It was just very lonely,” Schefter said. “He was always there and then he’s not, so suddenly. I was so sad. I tried not to think about it, but I wondered if I’d ever have the chance to work with him again.”

The crew felt the same. “Our playoff shows that year just felt flatter,” Markman said. “We really missed him on, and off, the air.”

On TV, Mortensen doesn’t seem like the needling type. “But he was,” said Chris Berman. “I never gave an edict not to make fun of me, but not many people did. He always had the privilege to poke the bear. Everybody there knew I’d talk to Andy Reid every week; we were close. So something would go wrong for the Chiefs, an interception or something, and Mort would call out, ‘Hey Boom! Did you call that play?’”

Berman (“Boom,” or “Boomer,” to ESPNers] had his teams. He grew up loving the Jets. He bonded with the Bills, the Niners and others later on. Sometimes, after finishing “Sunday Countdown” he’d be late walking into the room where the crew would gather to watch all the Sunday games. Maybe he’d come in midway through the first quarter of the early games. He’d ask, “What’s going on in the games?” Invariably, Mortensen would say something like: “21-nothing Jets, Boom.” Regardless of the score.

Said Berman: “On the air, for years, he kept us honest. Off the air, he kept us loose.”

Then came the dark period. One day, early in his treatment, Mortensen heard from Bill Parcells.

“So I’ve had this conversation with several people, including our own children,” Parcells said. “Some things can put us in dark places. Financial despair, the loss of a job, the loss of a loved one. In Chris’s case, a very serious ailment that can possibly result in death. It’s dark, it’s very lonely, it’s depressing, you feel at a loss, you feel ‘Poor me.’ I told Chris: It’s what you do after that. There are people who are concerned, who are caring and loving, but really, at the end, it’s about what you do. You have to handle this.”

Five weeks of chemotheraphy, beginning in February 2016. Two weeks off for recovery. Two months of chemo and radiation. More time off. Then the cooking. Then the dark moments. “You just make sure your affairs are in order,” Mortensen said. That’s when his faith helped. He’d been a wild child in his early newspapering days; Micki helped lead him to religion. She’d play the quiet preaching of evangelical Christian pastor David Jeremiah often in their home. “I often thought about what Parcells said because it rang true,” Mortensen said. “Though I’d say it’s an attitude I’ve had throughout my life … This is also where my Christian faith served me well, because the Bible tells us we will have troubles in this world but we are to cling to the light, the love and promise of God.”

Mortensen became a friend of Jeremiah’s and later got close with his son, Daniel, whom he helped become an NFL analyst. “We’d never go very long without speaking,” said Daniel Jeremiah, now with NFL Network. “He’s never asked me for anything in life. But now he’d say to me, ‘I’ll be fine. Pray for Micki. Micki needs your prayers.’ ”

“We’d talk,” said Tom Coughlin, “and he never gave you the impression he was in dire straits. But I knew what he was going through.”

Merril Hoge, survivor of cancer of the lymph nodes, flew to Houston to be with Mortensen—unasked. He sounded like a preacher when asked what his message was to Mortensen. “Unless you’ve been in the battle,” Hoge said, “you really don’t understand it. Death was looking at me for seven or eight months. I was in bed one day, so sick that I couldn’t even reach for the phone to call 911. I just wanted to say a few things to him. Like: There will be days like that, where you simply will not win; you’ll survive. It will suck the life out of you. It will leave holes in you. But now, you just gotta walk the plank, brother. Eighty percent of your survival is on you. Be you! I said to him, ‘Till we meet again.’ When we’d talk, I’d always leave him with that.”

In the dark days, he’d hear from his friends. He’d get video messages—one powerful one from cancer survivor Chuck Pagano, the Colts coach, who battled leukemia in 2013. “My cancer pales in comparison to what he went through,” Pagano said. “He was a frickin’ warrior.”

He’d have to be again, starting last November. Stage four cancer means there’s disease in the lymph nodes, and that means cancer can spread indiscriminately to other areas of the body. In late August 2016 scans showed spots on Mortensen’s left lung. They were biopsied in November. Malignant. Mortensen was still recovering from being taken to his physical edge by the chemotherapy and radiation, so more of that was impossible. Starting in December he began IV immunotherapy treatment for 30 minutes every three weeks. Last week was his 15th treatment, and a scan showed the nodules on his lung continue to get smaller. Mortensen says this is the only time he gets anxious—waiting for the scans to see if the tumors are smaller. The news has been good so far.

“There’s no definitive end to treatment for now,” Mortensen said this week. “But my oncologists have been fairly optimistic from the start. I’ve asked how long this will go on, and they say maybe forever. I’m still clean at the original site.”

No guarantees. And no guarantees some future scan won’t show the cancer somewhere else.

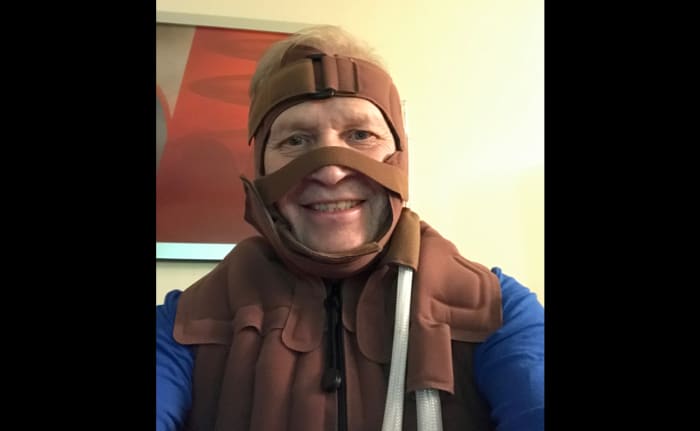

There’s one other issue. As a byproduct of his cancer treatment, Mortensen developed lymphedema, which causes affected areas to swell and retain fluids due to the damage to the lymph nodes from the intense radiation. For 45 minutes, twice a day, morning and night, Mortensen dons an odd-looking brown hood and vest, fitted with compression devices and a pump. The device helps his lymphatic system to drain properly, preventing fluid buildup in his neck pathways. The hood does provide some very slight comic relief—Mortensen looks like a Monty Python character in it.

Mort wearing the compression device he uses as therapy for his lymphatic system, which was damaged by cancer treatment.

Courtesy Chris Mortensen

You never think of things like that when cancer comes up. It’s all about eradicating the disease. Another issue Mortensen deals with is radiation’s effects on his salivary glands. Mortensen fights dry mouth all the time now. Jim Kelly, survivor of cancer of the jaw, turned him onto lozenges that increase the saliva in his mouth. They help. And he carries a spray to activate saliva in his mouth. When we met recently at his hotel near the ESPN campus, I recorded a 70-minute podcast with Mortensen, then a 25-minute video interview. Then we just talked. He sounded fine. Before I arrived, he had sucked down four of the lozenges, and he used the spray several times when I was there.

On TV, he sounds like the old Mortensen. He looks close to his old self, too, except 20 pounds lighter; and his hair has come back grayer.

“Life’s good right now,” he said.

A year before he was diagnosed, Mortensen tweeted a bombshell about Indianapolis reporter Bob Kravitz’s post-AFC Championship Game report that the NFL was looking into whether the Patriots’ footballs in the game had been purposely underinflated. Mortensen said in the tweet that 11 of the 12 balls New England had available for use on offense were underinflated by at least two pounds. NFL footballs, at the time, had to be inflated to between 12.5 pounds and 13.5 pounds per square inch. Mortensen wasn’t the only one to report on the deflation story; a source told me that Mortensen’s original story was correct, and I reported that.

In fact, the lowest of the readings on the Patriot footballs was 10.5 psi, so only one football, per the NFL’s Ted Wells Report on the controversy, was two pounds below the rule. What’s more, the cause of any pressure loss could be questioned because of something the NFL neither knew about nor acknowledged at the time they opened a probe into the case: the ideal gas law, the scientific principle governing the behavior of gases, which makes it clear that changing atmospheric conditions would affect the air pressure of footballs—and in the case of the AFC Championship Game, decrease it significantly. In any case, soon after posting his tweet, Mortensen began referring to the footballs as “significantly deflated” or “deflated.” He did not remove his original tweet until August (two months after the Wells Report proved it wrong). His intransigence enraged the Patriots and followers of the team.

“Do you regret not having an issued a correction on that original Tweet?” I asked.

“Yeah, I do,’’ he said. “We did on the website page eventually. But I should have tweeted something … I would have had no problem whatsoever [with a correction] because I had already asked them to clarify. Correct my story, please. And the Patriots felt like they were being smeared, because obviously it was in the furor that it created. I would have been fine with [a correction].’’

The correction wouldn’t have mattered much to the six-state region that loved the Patriots. New England was enflamed over the thought that Mortensen’s reporting spawned the NFL’s investigation—likely a flawed premise, but there was no convincing Patriot fans that the NFL would investigated the issue thoroughly anyway—and took it out on him. ESPN sits on the southern edge of Patriots country, in central Connecticut. Mortensen and his wife rented a house there for the 2015 season, and he eventually sent her back home to Arkansas after some death threats he received. “I got some that concerned me.’’ But, Mortensen said: “I think it is absolutely ludicrous to suggest reporting like that led to the NFL hiring Ted Wells and spending $8 million on [investigating Deflategate].”

There won’t be universal agreement on that, the same way there wasn’t agreement on the non-deletion of the tweet. He said he got a tweet recently—he assumes from a Patriots backer—that said, “You haven’t died yet?” It made him laugh, he said, because it’s the kind of sharp barb he might throw at a friend. It’s the kind he’s back to throwing at his new team now, with Berman and “Countdown” fixture Tom Jackson having stepped away from the show.

“It’s like having your best friend back in school,’’ Schefter said. “The mood is lighter. The room is funnier.”

One more story: In the middle of Mortensen’s treatment, close friend Ed Werder got a text from Mortensen. Werder’s son-in-law, Trey, died of cancer in 2016, leaving Ed’s daughter Christie a widow. Said Werder: “The text said he knew all that our family had endured with Christie and Trey. He said he had lived twice as long as Trey already and that if only one of them could survive cancer he would have preferred it to have been Trey because he and Christie were just starting their lives together and Mort had lived so much more of his.’’

Werder was overwhelmed. “But that’s who Chris is,’’ he said.

Those who know Mortensen well say that even in the throes of his continuing treatment and a competitive job, he’s stayed serene. “I think he’s at peace with what he’s done, and the kind of person he is,” Berman said. “I think he likes what he sees when he looks in the mirror. I think Mort’s pretty happy with Mort.’’

Battling a life-threatening illness is a transformative experience, and those who’ve been through such an ordeal learn much about themselves and those around them. Mortensen says the past two years have brought out more of his humanity—he’s told his three brothers he loves them, for the first time in years—and he has been overwhelmed by the support he’s gotten from family, friends and colleagues in the NFL community, and as well as by the professionalism of the doctors and other medical staff that have worked with him. He shows off iPhone pictures of his caregivers, for instance, in Houston. In the Book of Mort, this is the most valuable lesson of the last two years:

“Share the emotions that you feel for people when you have the opportunity. If you love somebody, tell them. If somebody has done something for you, tell them you appreciate it. Don’t let the moment pass you by. Because you never know when you’ll have another chance.”

Question or comment? Email us at talkback@themmqb.com.