Remembering Dr. Z, Who Reshaped How We Understand Football

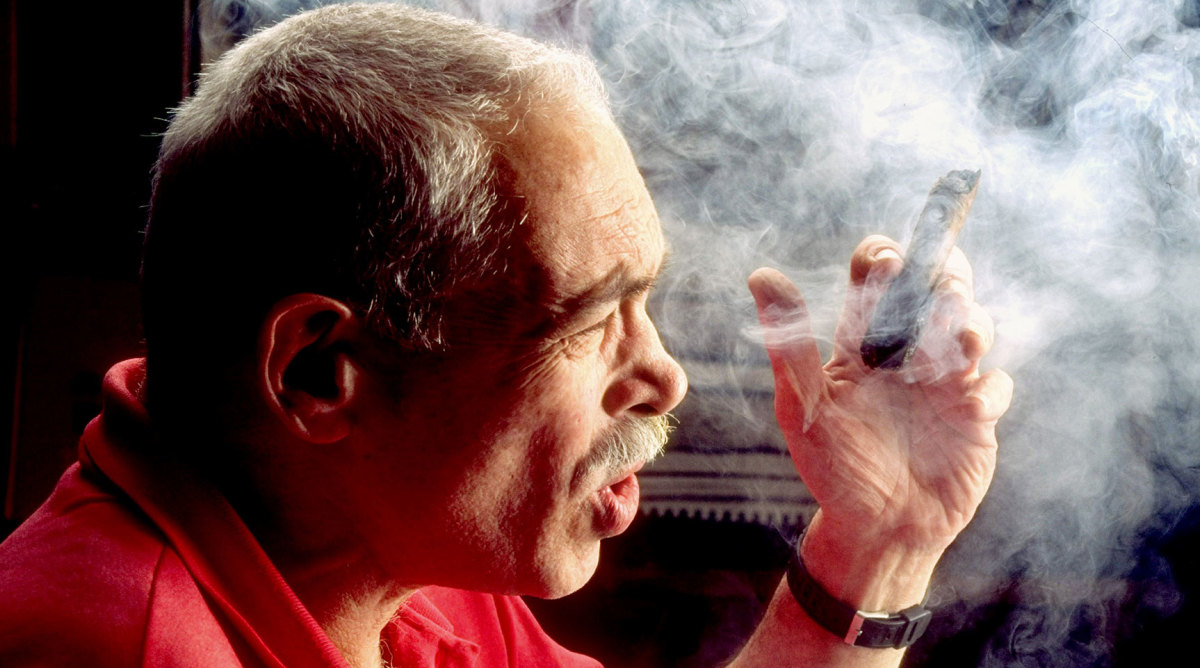

There’s one photograph of Paul Zimmerman, the longtime Sports Illustrated football writer, that seems to encapsulate the man perfectly. Zimmerman is holding a lit cigar in his left hand, plumes of smoke are gathering around his head, and, in this moment, the camera catches him mid-sentence. It’s easy to imagine him sitting at a dinner table, fine wine at hand, engaged in another football debate, lecturing you on the greatness of Marion Motley or Spec Sanders.

Zimmerman worked at Sports Illustrated for nearly 30 years, and during that time he became perhaps the most recognizable football writer of his time. He was known as Dr. Z, the football savant who was never lacking in knowledge or opinions.

Dr. Z was still writing regularly for SI and SI.com until 2008, when he suffered the first in a series of strokes that forced him into retirement and robbed him of his voice. After 10 years of struggling with his health, Paul Zimmerman died on Thursday. He was 86 years old.

• WHEN HE WAS Z: More from Tim Rohan on the life of Paul Zimmerman

Bill Belichick, the Patriots’ coach, called Zimmerman one of the most respected and most connected football writers, of his era. “Paul was a great ambassador for professional football,” Belichick said. “Certainly a sad day to hear about his passing.”

Perhaps most of all, the football community will remember Zimmerman for his ability to explain the game—and educate the average fan. It helped that he’d been a football player himself. He played offensive line for a few years at Stanford, and then coached the equivalent of the junior varsity team while he studied journalism at Columbia. When he got into sportswriting, then, in the 1960s, he approached it with an insider’s view, something few other writers were doing as the modern NFL was taking shape.

“He didn’t play at the highest level, but he had an understanding of what really goes on,” said Matt Millen, the former All-Pro linebacker whom Dr. Z covered throughout his career and remained friends with afterward. “I thought, for the football writers of his generation, he was at the top of the list.”

Dr. Z soon gained a reputation around the league for the meticulous way he worked. He’d chart games using an elaborate color-coded system. He’d clock the hang time of punts and the length of the national anthem. He’d watch film on his own and dissect plays and schemes as if he were a coach or player.

Belichick said that, when Dr. Z asked a question, it was more in-depth than your typical reporter. Dr. Z talked the same language the coaches did.

“He brought an offensive lineman’s approach to the game, and those guys tend to be cerebral or analytical,” said Bill Polian, the Hall of Fame general manager. “They tend to be the guys that really delve into the detail. He had that mindset, which is very different from the typical guy who covers pro football.”

• MY LIFE IN JOURNALISM: Paul Zimmerman on his five decades as a writer

Dr. Z carried that passion—that intensity—into his writing, too. At SI he was notoriously tough to edit; he fought over every word, wanted to make sure his analysis was portrayed accurately. He once told a fellow writer, “You know, there’s a thin line between working hard and obsession. And I think I’ve crossed the line.”

Ultimately, Dr. Z reached heights that few sportswriters do. He wrote 14 Super Bowl stories for SI, and helped teach the game to countless numbers of fans, as football grew into the most popular sport in America.

“There’s no question that he made a significant impact during the embryonic years of pro football,” said Hall of Famer Ron Wolf, the longtime Packers GM. “That’s his legacy.”

Later in his career, Dr. Z started writing a column for SI.com and opened up more about his life outside of football. He often wrote about wine—he considered himself an expert—and his second wife Linda, “the Flaming Redhead.”

• BEST OF DR Z: Paul Zimmerman’s greatest Sports Illustrated stories

Zimmerman would’ve probably kept writing, too, if it weren’t for those strokes. In his final years, he could only communicate by saying, “Yeah,” or “no,” or giving a thumbs up or thumbs down sign with his left hand. If he tried speaking in full sentences, every word would come out as “when, when, when…”

The cruel irony of that was not lost on Zimmerman’s football friends.

“He’d get so frustrated that he couldn’t get words out,” recalls Matt Millen. “We used to joke with him, ‘You know, Z, you’re a lot more fun to be around now that you can’t speak.’ And he loved it. He’d laugh, and he’d just kick me. I just, I really enjoyed him. He will be missed.”

Question or comment? Email us at talkback@themmqb.com.