Tim Green’s ALS Announcement Leaves Us Once Again Pondering Football’s Toll

Sunday’s NFL slate included a handful of games that looked awfully meaningless to most of us, which is what happens when October gives way to November, and early-season hope is replaced in many markets and locker rooms by the realization that this is not your year. But while you and I can watch football with a sense of resignation and detachment, the players cannot play it that way. Every game matters, whether you want it to or not.

A clear testimonial to that effect followed CBS’s broadcast of the 3-6 Broncos at the 7-2 Chargers; you didn’t even have to touch the remote. On “60 Minutes,” Tim Green, a pass-rusher who played eight seasons for the Falcons (seven of them playoff-free) after they picked him 17th overall in 1986, announced that he had been diagnosed with ALS (amyotrophic lateral sclerosis), Lou Gehrig’s Disease.

Green, 54, is not the first ex-NFLer to develop the disease; the link between the violent game and the degenerative and fatal neurological condition, which causes sufferers to lose most control of their muscles and is diagnosed in two to three out of every 100,000 people annually, has grown somewhat clearer with time. Niners great Dwight Clark succumbed to ALS this summer, at 61; ex-Saint Steve Gleason and ex-Raven O.J. Brigance, among others, have been visible in their battles against ALS’s progression for years. When Kevin Turner, a former Patriots and Eagles fullback, died at 46 of ALS in 2016, researchers with Boston University and the Concussion Legacy Foundation examined his brain and concluded that head-trauma-related CTE had caused his ALS.

But Green’s personal history made the revelation of his diagnosis all the more arresting. The modern NFL offers no analogue to who Tim Green was and what he became—maybe John Urschel crossed with Michael Strahan? Green graduated summa cum laude from Syracuse; during his playing days he delivered commentaries for NPR and wrote a column for the Syracuse Herald-Journal. Coach Jerry Glanville once caught him reading War and Peace before a game. After leaving the NFL, he became a TV host and prolific author of children’s books; he also finished his law degree and joined a leading upstate New York firm.

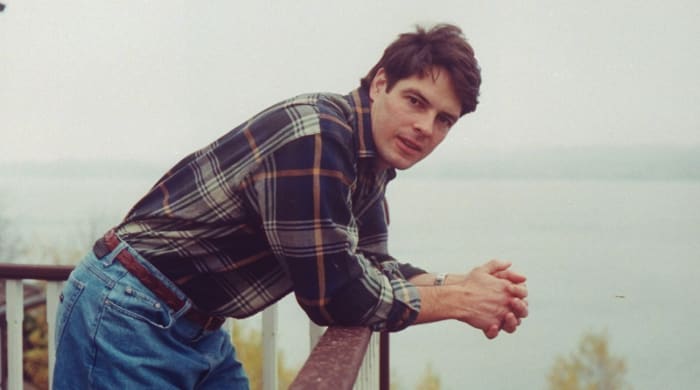

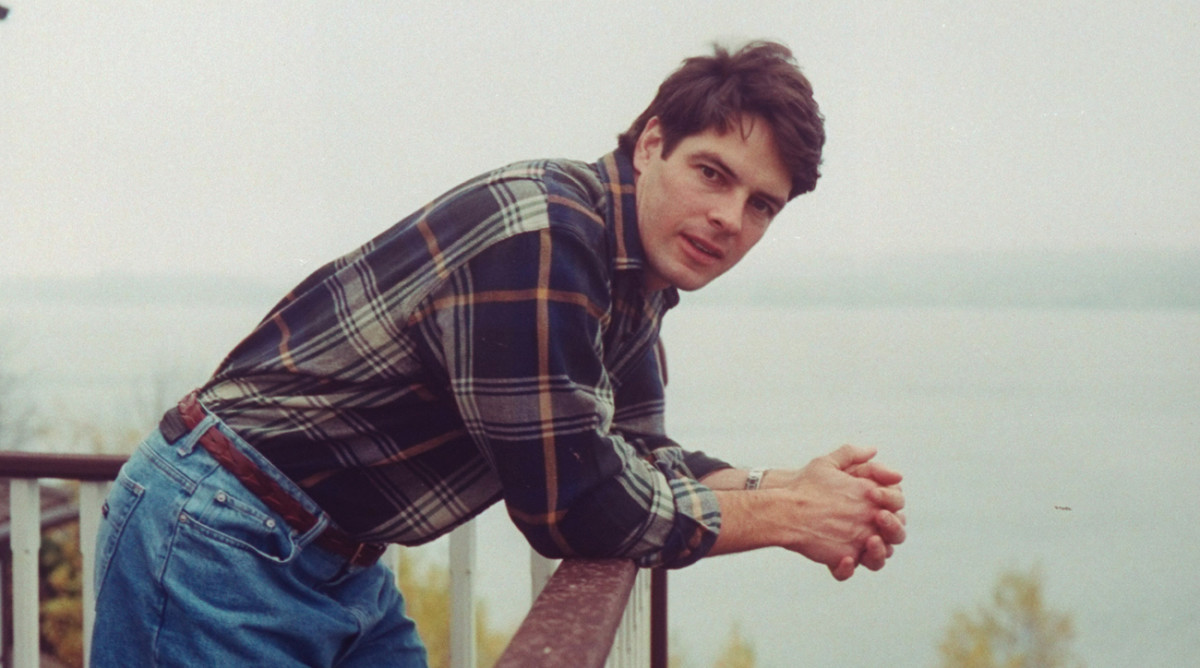

The “60 Minutes” segment, which is very much worth watching, incorporated footage from a previous piece Steve Kroft had done on Green in 1996, three years after his retirement. Green, pictured then as a strapping ex-jock wearing the billowy athlete fashions of the mid-’90s, told Kroft that NFLers would willingly take 10 to 20 years off the ends of their lives to play football.

“I stand by that,” Green said in the new interview, in a weakened and slurred voice. “I’ve maybe taken that much off the end of my life. Maybe more. I don't know.”

When Urschel walked away and when 49ers linebacker Chris Borland did the same before him, with options abounding and their brains intact, the press covered their decisions as feats of rationality. When retired players found themselves suffering from a bewildering new disease, they were blindsided victims. And those who played on despite knowing the prevalence of CTE were just gladiators, sacrificing their bodies to vault their families out of poverty, rational in their own way.

All three types are mixed in Green. He knew the risks and, thanks to his smarts and charisma, had options beyond football. Still he played. He just loved the game too much. His career, he told Kroft, “was as magical and wonderful as I dreamed it would be.”

And as he played, he led with his head on every snap. He didn’t retire or change his ways after his first concussion, or his fifth, or even his 10th, at which point he just stopped counting. Green’s wife, Illyssa, said his head would get so swollen from training-camp collisions that he’d have to cover it in Vaseline just to slide on his helmet.

Green’s story also differed from familiar NFL head-trauma stories in another way—it was saddening but not sad. Green, surrounded by a loving family, seemed upbeat. He said he considered himself blessed. Using special software, he continues to write; he’s on his 39th book. He exercises. He’s enlisted a number of big names to “Tackle ALS”; the initiative has raised nearly $1 million for research so far. And he still coaches youth football.

One image from Sunday night sticks with me now and will, I suspect, for a long while. A brief shot depicted a stooped Green perched in a chair on the sideline as his 12-year-old son’s team played football—contact, not flag.

Kids don’t see the world the way we do. They can be cruel when it comes to matters of difference (disability, say), and they can be shallow (obsessed, perhaps, with fame and fortune). But they can also possess a stark moral perspective that adults, having long ago made our dozens of necessary-seeming compromises to get on with our lives, lack. What, I wonder, did they make of their coach?

Question or comment? Email us at talkback@themmqb.com.