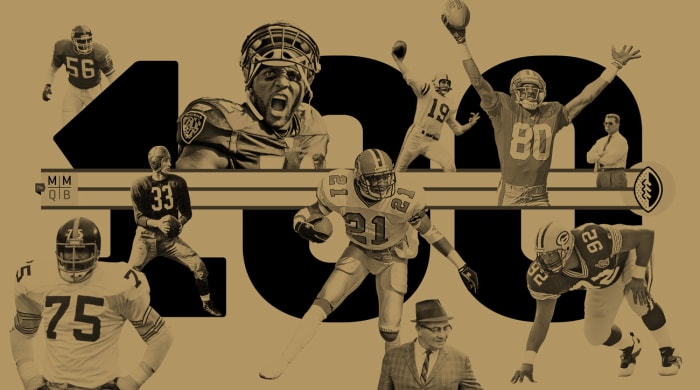

100 Figures Who Shaped the NFL’s First Century

You could easily fill out a list of 100 influential people in football’s history just with great players, coaches, owners and commissioners. But the NFL’s story ranges beyond the field and the front office, and pro football has been shaped not just by the stars who rule the record book, the X’s and O’s experts who cooked up its strategies, or the power brokers who turned it into the most dominant sport in America. There are also unorthodox, sometimes unfamiliar personalities who injected color into the game, rogues who worked outside the rules and brought disrepute, and figures from related fields—media, medicine, money—who profoundly transformed pro football, and our experience of it. This list is not meant to be definitive, and you could compose another, with a whole host of new names, that would be valid and compelling. Omissions should not be considered slights. Rather this is meant as a mosaic, a picture with 100 pieces from which, when they’re fit together, an image of the NFL at the century mark emerges.

Capsules by Ben Baskin, Andy Benoit, Mitch Goldich, Jonathan Jones, Kalyn Kahler, Robert Klemko, Mark Mravic, Conor Orr and Jenny Vrentas.

Lyle Alzado

Defensive wild man who admitted to PED use and blamed it for the brain cancer that killed him

Lyle Alzado terrorized opposing quarterbacks during his 15 seasons (1971-85) with the Broncos, Browns and Raiders. The defensive end was not only one of the most feared players in the league—a two-time All-Pro and AFC Defensive Player of the Year in ’77—but he was also one of the fiercest and most violent, prone to random outbursts of anger. In one famous incident, Alzado ripped the helmet off an opposing lineman and rifled it at him. The play caused the NFL to adopt the so-called “Alzado Rule,” where the removal of an opposing player’s headgear would result in an ejection and possible fine.

With a rippling 255-pound physique, Alzado was also the paragon of fitness in the league. But after retiring and being diagnosed with brain cancer in April 1991, he admitted he had taken anabolic steroids from 1969, when he was in school at the now-defunct Yankton College, all the way through his failed NFL comeback attempt in 1990. As he underwent chemotherapy, Alzado became an outspoken advocate warning of the dangers of steroids, believing that the drugs caused his disease, although there was no proof this was true.

As a Raider, Alzado was a Los Angeles celebrity, the perfect match of player personality and fan base, as he helped lead the team to a Super Bowl win in the 1983 season. But his tenacity on the field was not natural; Alzado once estimated that he spent as much as $30,000 a year on steroids. And with his series of well-publicized physical altercations after retirement—once accused of brandishing a gun after a road-rage dispute, another time accused of attacking a female deputy marshal who tried to serve him papers—as well as his cancer diagnosis and outspoken nature, Alzado brought increased attention to the potential harms of steroid use.

A few months before Alzado died at age 43 he said: “If what I've become doesn't scare you off steroids, nothing will.”

Dr. James Andrews

Orthopedist who revolutionized joint surgery, saving countless athletic careers

During the Wild West days of athlete injury and recovery, Dr. James Andrews broke through to establish himself as the world’s most prominent surgeon for high-end performers. With a client list ranging from Roger Clemens to Adrian Peterson, Andrews’ steady hands have been the guiding force in some of the most prominent surgeries in modern sports history.

Especially in the NFL world, where a torn ACL was once a career-ender but is now understood to be a year-long recovery, Andrews is known as an industry leader. Doug Williams, Bruce Smith, Donovan McNabb, Sam Bradford, Dalvin Cook—all took their serious knee issues to Andrews. Peterson might have been Andrews’ most remarkable patient. The Vikings All-Pro blew out his knee on Christmas Eve 2011 and had surgery six days later. The following year he came within eight yards of the single-season rushing record.

In 2013 The MMQB’s Jenny Vrentas wrote a first-hand account of Andrews as he operated on the knee of former Giants safety Stevie Brown. The details of the operation, which involves a drill and gallons of saline solution, shed light on how routine Andrews has made a complex procedure seem. Quite simply: He is the man who can put athletes back on the field sooner. And while he refused to take credit for the turnarounds of many football, basketball and baseball players (as well as golfers, and professional wrestlers such Shawn Michaels, C.M. Punk and Rey Mysterio), there is no doubt a vast gulf between the way we see these injuries now and the way that they were viewed just a few decades ago.

It’s nearly unfathomable to think about the advances that joint surgery and subsequent recovery have taken over the years. Career-ending knee and shoulder injuries used to be all too commonplace across sports, robbing football of some of its greatest names in their athletic prime. Andrews has been at the forefront of giving players a second life in a sport that often seems hellbent on showing them an early exit.

Roone Arledge

Creator of Monday Night Football

The NFL wouldn’t be where it is today without a few visionaries on the television side. Consider Roone Arledge, a long-time ABC executive, one of them.

As the inventor of or creative force behind tentpole programs such as the foundational and long-running Wide World of Sports, Arledge was a legend at ABC and ABC Sports. News coverage, campaign coverage and breaking news all bore his fingerprints, evident by the dozens of Emmy awards he pocketed, the auditorium named after him at Columbia’s prestigious school of journalism, and the recognition he received from the Pro Football Hall of Fame.

While Arledge’s most exceptional work might have been the coverage of the terrorist kidnappings and murders at the Munich Olympics, which, according to his obituary, changed forever the expectations of the modern television viewer, who had been accustomed to hanging by for the nightly news, the creation of Monday Night Football was seminal in raising the image of the NFL in the American consciousness. From there came Howard Cosell and Don Meredith, and the idea that a weekly matchup could be the all-consuming campfire that a collective country might settle around, not unlike a favorite sitcom or news program. (Gamblers loved it, too, as a last chance to get even for the week.)

While the sport’s popularity and MNF itself has ebbed and flowed throughout the years, with divergences down the road including comedian Dennis Miller and sports columnist Tony Kornheiser, Monday Night Football remains a league standard; a rite of passage for any first-time head coach or player cementing his status under the league’s brightest lights.

Sammy Baugh

Biggest star of the ’30s and ’40s

Before the days of Peyton Manning and his milquetoast insurance ads, there was football’s true dual threat—or in the case of Sammy Baugh, quadruple threat.

Baugh could act, as he did in starring as Tom King in King of the Texas Rangers, but he could also play safety. And punt. And, most notably, reinvent the game as a downfield-slinging quarterback.

No quarterback has more seasons leading the league in passing (Baugh is tied with Steve Young for that honor). No quarterback has more years with the league’s lowest interception percentage. Baugh’s rambling style was the model for quarterbacks who would come to change the face of the game decades later, with their ability both to move the pocket and to torture defenses by elongating the play. A three-sport star at TCU (football, baseball, basketball), Baugh initially sought a career in baseball before getting drafted by the Redskins, leading the team to a championship in his first season.

A lifelong signal-caller in Washington, Baugh elevated the game at a time when the actual football was puffier and harder to throw. That didn’t stop him from loading up on touchdown passes while the rest of the league was still coughing up dust, leaning on the strength of the run. Patriots coach Bill Belichick compared Baugh to both Tom Brady and Ed Reed, for his ability to move the ball on one side of the field, then stop it on the other. He finished his career with 31 interceptions for 491 return yards, along with 187 passing touchdowns and nine rushing TDs.

Odell Beckham Jr.

Quintessential player of the social media age

Odell Beckham Jr. catapulted to fame as a rookie when he made a one-handed catch while falling backwards on Sunday Night Football in 2014. That catch launched Beckham into a stratosphere of crossover digital-age fame that previously only NBA players had really reached. The LSU product has a huge presence on social media, and has influenced young NFL fans with his signature hairstyle, unique fashion sense and outsized personality.

Beckham’s brand centers around his refusal to conform to the league’s expectations that players will fall in line, not be distractions and not speak out about their team. He set off a firestorm of news and social media reactions when he discussed the Giants quarterback situation and his thoughts on his team in a taped interview on ESPN during the 2018 season. Beckham doesn’t hide his emotions, and his uninhibited reactions are the reason he’s a bigger social media presence than any NFL player before him. His appeal, however, transcends the NFL, and he’s as likely to turn up at runway shows and or a fashion shoot as he is to spark the latest hot-button issue on TV shout-fests. Beckham has been suspended for fighting with rival cornerback Josh Norman, he’s taken out his in-game frustrations on a kicking net, he’s wept, he’s been fined for celebrating a touchdown by mimicking a dog urinating, and his trade from the Giants to the Browns in the 2019 offseason will test whether a move from New York to Cleveland might actually make an athlete a bigger national star; if anyone can pull it off, it’s OBJ. Beckham has become the quintessential sports personality of the social media age, an athlete a younger generation of fans can relate to.

Chuck Bednarik

Last of the great two-way players; central figure in an iconic NFL photo

Chuck Bednarik is described on his Hall of Fame plaque like so: “Rugged, durable, bulldozing blocker, bone-jarring tackler.” For the man known as Concrete Charlie, perhaps one of the most apt nicknames in sports history, it is a description that harks back to a bygone era in the NFL, when Bednarik the linebacker roamed the middle of the field looking to deliver crushing blows on opposing offensive players, and Bednarik the center battled in the trenches, looking to deliver crushing blocks on opposing defensive players. In the offseason, the NFL’s last great 60-Minute Man would, fittingly, sell concrete.

Bednarik was a six-time first team All-Pro and a two-time NFL champion and, despite being better known for his ferocious play as a defender, was voted as the NFL’s all-time best center in 1969. While others, such as cornerback/receiver Deion Sanders, would play on both sides of the ball after Bednarik, none would do so at such physically demanding positions as the longtime Eagles great. When fans bemoan the (somewhat) safer game we see today, it is the halcyon era of Bednarik and his brand of brutal, old-school, smash-mouth football they’re pining for.

Nothing epitomized that era better than John G. Zimmerman’s 1960 Sports Illustrated photograph of Bednarik standing over the motionless body of Giants running back Frank Gifford. It was the closing minutes of a November game at Yankee Stadium, with Philadelphia and New York battling atop the Eastern Conference. After Gifford caught a pass from quarterback George Shaw, there was Bednarik to deliver one of those patented bone-jarring tackles; the ensuing damage knocked Gifford unconscious, caused a “deep brain concussion” (in a time when concussion was a somewhat foreign word), sent the running back to the hospital for several days and out of the NFL for nearly two years. While Bednarik long maintained he was not celebrating the hit and Gifford never blamed him for the injuries, the image of the linebacker looming over the motionless body, fist pumped in celebration, entered into NFL lore.

Bill Belichick

Mastermind of a two-decade dynasty in New England

Bill Belichick will go down as the greatest coach in NFL history, and think of all the presumption that quashes. He was never the hot young coach. In fact, he was the antithesis of an exciting hire in New England: a 47-year-old retread coach with a career record of 36-44. He wasn’t known for a revolutionary trademark scheme. He wasn’t a particularly charismatic public orator. He was often gruff with the media. He showed little to no dramatic leadership flair. In central casting, Belichick would sooner be pegged a tax attorney than an NFL head coach.

And yet, if Bill Belichick were to retire tomorrow, his six Super Bowl titles as a head coach and eight total as an NFL coach would both be records. So would his 10 consecutive division titles. And nine conference titles. And 13 conference championship game appearances. And so on and so on.

Belichick’s successes emphasize something about pro football that is understood, but not fully appreciated: It is the ultimate sport of strategy and scheme. You might hear a really well-schemed football game likened to a chess match. But in football, the piece all move simultaneously, not one at a time. The movements are not constricted to individual squares and, most importantly, not everyone’s pieces are the same. Imagine chess if one player’s bishop were different from another’s. Or if one player had a pawn that, if used in certain ways, could be more powerful than a rook.

This is what football coaches think about, and none better than Belichick. He is a master at identifying and leveraging individual players and their attributes. Which is why his Patriots teams have never had one clear identity. Belichick finds smart, uniquely gifted players and shapes his scheme around them—and for their opponent—each week. Some of his Patriots teams have evolved more in a month than most NFL teams do in a year.

Bert Bell

Post-war commissioner who pulled the league from obscurity

Bert Bell, who saved a fledgling league from devouring itself, was a football lifer. A quarterback, a soldier, an owner and finally a decision-maker, Bell did everything from selling tickets to pumping up footballs; a reminder of when the game was controlled by the pure of heart, with their only interest in increasing its visibility and viability.

Over several conversations with his son, Upton, a few years back, we learned that Bell not only empowered the NFLPA and began tailoring a television schedule to culminate with big games at the end of the season, but he was an early champion of the draft. Fearing that the league would eventually become a few deep-pocketed super-teams, Bell told colleagues “I still worry about all the have-nots.” His legacy includes anti-gambling rules and sudden-death overtime, both essential to the integrity and watchability of the sport in his era and beyond, not to mention the merger of the NFL with the AAFC, bringing some of football’s most important franchises—the Browns, 49ers and Colts—into the fold.

Bell could be described as a lot of things, but Sports Illustrated football writer Paul Zimmerman might have put it best. He was a “fan,” which was obvious and a driving factor in nearly every decision he made. As the league, and sports business in general, grows more callous and corporate by the day, Bell is a reminder that there were once people like us in seats of high power. Back when the game was building a foundation that still stands today.

Chris Berman

Face of ESPN’s NFL coverage during the cable net’s dominant years

We don’t need football in order to live, and most of us don’t need it in order to prosper. And yet it can consume a significant place in our lives. Why do we invest so much into watching, playing and discussing the game? Because it’s fun. Simple as that.

On television, perhaps no one has more explicitly brought out the fun in football than former ESPN anchor Chris Berman. Big, loud and genial, he vibrantly trailblazed how the NFL is presented on TV. From 1985 to 2016 he was a mainstay on ESPN’s Sunday morning and Monday night pregame shows, but he shined brightest on Sunday evenings, hosting NFL Primetime with former Broncos linebacker Tom Jackson.

In the late ’80s and early ’90s, well before the Red Zone channels and just before the internet and prominence of DirecTV’s Sunday Ticket, Primetime was many fans’ richest connection to the NFL. Berman and Jackson took viewers around the league, presenting each game as its own story, with full narratives and analysis, while the best plays were shown over the enchanting Sam Spence tracks of NFL Films. Berman amplified the theater with sound effects and some of the best nicknames going: Andre “Bad Moon” Rison; Curtis “My Favorite” Martin; Eric “Sleeping With” Bieniemy; Reggie “A Stately” Wayne “Manor.” And, of course, there was the catchphrase (a tribute to predecessor Howard Cosell) that became popular not just in the sports world, but in the greater American lexicon: He! Could! Go! All! The! Waaaay!

Remarkably, Berman’s schtick did not compromise his dignity and journalistic chops. His one-on-one sitdown interviews were some of TV’s best, and he would shrewdly pick and choose spots to opine on some of the NFL’s political issues. But all of this, frankly, came second to the most important part of Berman: He made football fun.

Mel Blount

Hall of Fame Steelers cornerback whose physical style forced rules changes that opened up the passing game

One of the distinguished few NFL players who forced a rules change meant to slow him down, Hall of Fame cornerback Mel Blount created a legacy as one of the best defensive backs in NFL history over 14 seasons with the Steelers. In 1978, the league introduced what was informally known as the “Mel Blount Rule,” limiting contact between a receiver and defensive back to within five yards of the line of scrimmage. Like Night Train Lane before him, the 6'3", 205-pound Blount took the bump-and-run technique to new heights, manhandling opposing receivers on the fearsome Steelers defense that contributed to four Super Bowl victories in his time. “They really were trying to legislate the game to slow the Steelers down, especially on defense, because we were basically dominating the game,” Blount later told NFL Network. “I think any time a player can have such an effect on the game that they name a rule after you, it’s an honor, and it’s something that my kids can read about.”

Blount was a two-time All-Pro, five-time Pro Bowl selection and, on a defense loaded with future Hall of Famers, the 1975 Defensive Player of the Year. Despite his physicality, he missed just one game in 14 season. Former teammate Dwayne Woodruff told SI in 2009, “Mel could play in the NFL today. And he could play in the NFL tomorrow.”

Tom Brady

Six-time Super Bowl-winning Patriots quarterback

No athlete’s career arc comes close to Tom Brady’s. The 199th overall pick in 2000 has long been known as the NFL’s all-time greatest draft steal. That label eventually gave way, in many minds, to the NFL’s all-time greatest player. Brady’s record in Super Bowls alone, 6–3, is better than many a great quarterback’s entire postseason record. He has six rings despite a 10-year title drought in the heart of his career, meaning Brady has spearheaded dynasties in two different eras: the early 2000s (three titles in four of the waning years of the “run the ball and play defense” era) and late 2010s (three titles in five years during the NFL’s pass-obsessed era). Split his NFL life down the middle, and you’re left with two first-ballot Hall of Fame careers.

More impressive than what Brady has done is the way he has done it. He has won in various systems with various supporting casts, many predominantly comprising role players. Remarkably, the attributes behind his greatness are still overlooked. Everyone talks about Brady’s football IQ, and indeed it’s off the charts. But his arm, though not scintillating like an Elway, Favre or Mahomes, is stellar. And Brady’s mobility, not out of the pocket (obviously) but in the pocket (where it matters most), is second to none.

Brady also might one day be viewed as a pioneer in personal fitness. His evangelism for his TB12 dieting and workout methods (lots of veggies, and muscle flexibility over strength) can draw snickers, but the results—for him—have been staggering: Almost 42, Brady looks as good physically as he did at 32.

Brady also represents how reactionarily a public image is formed. In the early 2000s he was the boy next door—the underdog who kept beating the bigger, faster, stronger guys. But as Brady kept winning, the public’s envy and fatigue took over, and in some quarters outside of New England, Brady began being seen as an almost villainous superstar. The 2014 Deflategate scandal/conspiracy (depending on whom you ask) solidified those love/hate perceptions. But now, after he has accumulated too many rings to fit on one hand, the respect for Brady—even from the haters—has mounted so high that the only fitting approaches to him are respect and awe.

Jim Brown

Dominant ’60s running back and prominent activist who retired in his prime

Jim Brown is regarded by many as the greatest pro football player ever. The fact that he left the game at his peak is only further evidence for the argument.

In just nine NFL seasons, the Browns back racked up 12,312 yards while averaging an astonishing 5.2 yards per carry. He held the NFL’s career rushing record for 19 years—still the longest any rusher has held the title—and despite retiring in 1965, was in the top 10 in career rushing yards in the NFL for more than 50 years. Today he remains the only player in NFL history (with more than three seasons) to average more than 100 rushing yards per game in a career.

Brown led the NFL in rushing yards in eight of his nine seasons. Three times he was named NFL MVP. He never missed a game in his career. He led Cleveland to the 1964 NFL title, the Browns’ most recent championship. And he served as a black sports icon in the 1960s during the civil rights movement.

Brown’s retirement following his MVP-winning 1965 season shocked the sports world. Embroiled in a contract dispute with Cleveland owner Art Modell while on the set of The Dirty Dozen, Brown told SI’s Tex Maule, “I quit with regret but not sorrow.” He went on to have a successful acting career, though across the decades he faced numerous charges related to domestic violence.

He has served as an NFL ambassador for much of his post-playing career. Any number of players have called Brown the greatest ever, but take it from Bill Belichick, who’s known as a history buff. “Jim Brown is in my opinion the greatest player that ever played,” Belichick, the former Browns coach, said in 2016.

If you want to know Brown’s running techniques, who better to hear it from than the man himself? In 1960, he taught us all how he became the best rusher in the NFL in this SI spread.

Paul Brown

Dynastic and innovative Browns coach; later founder of the Bengals

Considered by many the godfather of modern football coaching, Paul Brown’s biography could extend for hundreds of thousands of words. But put simply: The familiar machinations with which the majority of successful coaches operate in the NFL today can almost all be derived from the behavior of Brown.

Before Brown, film study was not the norm. Nor was scouting as we know it today. Nor was hiring a coaching staff and deploying it across distinct areas of expertise. Of course, these are only the surface-level concepts that he gets credit for. Brown is to coaches what Chuck Berry is to guitar players; it’s far easier to find the things coaches do today that did not originate from one of Brown’s methods. Any time you think there exists a new sound or groove, it’s best to rewatch Brown’s A Football Life to make sure it wasn’t stolen.

With a tree that spawned the careers of Bud Grant, Chuck Noll, Don Shula and Bill Walsh among countless others, Brown led by example. Even if that example sometimes caused players to recoil—he was notoriously aggressive when it came to contract negotiations, and players remember him for a dictatorial streak—it was difficult to argue with Brown’s success. In 1946, the former Ohio State coach took over the fledgling Cleveland Browns of the All-America Football Conference and proceeded to win all four AAFC titles, then another three when the Browns migrated to the NFL. A seismic change in professional football came when Brown, who operated as the de facto GM of the team, split with Cleveland and its new owner, Art Modell, in a power struggle. Five years later Brown returned to football in Cincinnati, where he invested in the AFL’s newly formed Bengals and served as coach, GM and principal owner. Brown worked in Cincinnati until his death in 1991, eventually passing ownership of the franchise over to his son, Mike.

Despite all of his renowned success, it’s easy to trace Brown’s roots back to the genesis of his coaching career as a relentless competitor. Even though he won championships, revolutionized coaching and introduced some of the most cutting-edge play concepts of the time, he would view beating the Browns in 1970, the first year of the AFL-NFL merger, as one of his most satisfying victories.

Earl Campbell

Transcendent power-runner whose curtailed career highlighted the game’s physical toll

Before there was Marshawn Lynch or Adrian Peterson, there was the NFL’s consummate power back: Earl Campbell.

Once a No. 1 overall draft choice out of the University of Texas, before going on to a glowing NFL career that featured five Pro Bowls, three first-team All-Pro nods, an MVP award and three offensive player of the year awards, Campbell started life as a young worker on his family’s rose farm in Texas.

He grew up idolizing linebackers, which made sense when he was handed the reins as a running back in high school and never looked back. He became the face of the NFL’s physicality on the field, and its consequences off it. In 2012, he told reporters that the ailments he suffered from, including significant nerve damage, were almost certainly correlated to his playing style and heavy workload as a player.

Campbell finished his career with more than 2,000 carries, including four straight seasons of 300-plus attempts at its outset. While those numbers may eventually blend into the background (his career statistical comparisons are closer to those of Shaun Alexander, Clinton Portis and LeSean McCoy), Campbell is viewed by lifers of the game as one of the purest representations of a classic running back in the Jim Brown mold.

Campbell played his entire career with physical ailments aggravated by some band-aid surgeries. Whatever pain he was inflicting on his opponents was probably being felt doubly by Campbell, who struggled for a time with painkiller addiction following his playing days and was diagnosed with spinal stenosis in 2009. Some of Campbell’s greatest physical feats may have been overcoming the wave of side effects that hit him after the game. That being said, to see him romp into the end zone in the traditional NFL Films slow motion is to marvel at a work of art that will endure.

Lee Clow

Creative mind behind Apple’s revolutionary “1984” Super Bowl commericial, which transformed advertising and the NFL championship broadcast

Midway through the third quarter of Super Bowl XVIII on January 22, 1984, Pat Summerall sent the CBS broadcast to commercial. What came next transformed television history.

Scene: An army of gray-clad drones shuffles in lock-step as an ominous voice intones portentously about the control of information. Cut to a young woman in white tank top and red shorts carrying a sledgehammer and pursued by gray-clad troopers. As a giant face on a screen in a bleak auditorium harangues the audience—“our Unification of Thoughts is more powerful than any fleet or army on Earth!”—and bellows out, “We shall prevail!” the woman spins and hurls the hammer. The screen explodes, unleashing a blast of wind that sweeps over the slack-jawed drones.

“On January 24th, Apple Computer will introduce Macintosh. And you’ll see why 1984 won’t be like ‘1984.’”

To introduce the groundbreaking Macintosh computer, Apple founder Steve Jobs wanted something dramatic and unexpected. He turned to Chiat/Day creative director Lee Clow, a star in the advertising world, who devised a 60-second spot that drew on the dystopian aesthetic of George Orwell’s 1984, enlisting Ridley Scott (Alien, Blade Runner) to direct at a cost of $900,000, and pegged it for the Super Bowl, the most watched program on American television.

The ad ran just once nationally, on that Super Bowl broadcast, but the impact was instantaneous. The next morning the talk was more about the mind-blowing commercial than the Raiders’ blowout of the Redskins, and the “Super Bowl ad” phenomenon was born. In the years to follow, the commercials became phenomena in themselves—from Spuds McKenzie to “Nothing But Net” to “Dilly Dilly”—drawing huge non-football audiences to the game and generating massive (free) media coverage for sponsors. “Our vision was more about the idea of how the world was going to change because of computers—not that we were changing the Super Bowl that day,” Clow told Bloomberg Newsin 2014. “But it did create a phenomenon where people started designing advertising specifically for the Super Bowl. … In the advertising business, you don’t often get to be a part of something that important, that world-changing.” Macintosh changed the computer industry; “1984” changed advertising, and the NFL.

Don Coryell

Passing-game genius who forced defenses to adapt in the game’s constant strategic ebb-and-flow

Some of pro football’s greatest innovators, especially on offense, have come from the college ranks. There’s perhaps no better illustration than Don Coryell. A journeyman at small colleges from 1950 to ’60, Coryell was the head coach at San Diego State from 1961 to ’72 before joining the St. Louis Cardinals in 1973. In ’78 he moved to San Diego, where he had his most famous stint, with the Chargers for nine years.

Coryell’s understanding of how to weaponize a downfield passing game dated to his time at San Diego State, where necessity was the mother of invention. As he explained several years after leaving there, according to the San Diego Union Tribune and San Jose Mercury News, "We could only recruit a limited number of runners and linemen against schools like USC and UCLA. And there were a lot of kids in Southern California passing and catching the ball. There seemed to be a deeper supply of quarterbacks and receivers. And the passing game was also open to some new ideas. Finally we decided it’s crazy that we can win games by throwing the ball without the best personnel. So we threw the hell out of the ball and won some games. When we started doing that, we were like 55-5-1.”

Coryell’s downfield route combinations changed the NFL. His high-flying offensive approach, known as Air Coryell, swept the league in the late ’70s and early ’80s. With the Chargers, Coryell’s offenses ranked, in terms of total yardage, 4th, 5th, 1st, 1st, 1st, 1st, 4th, 1st and 12th (Coryell’s final season, in which he was fired after a 1-7 start).

Coryell’s omission from the Hall of Fame remains one of the hottest debates among football cognoscenti. Voters don’t like that he never reached a Super Bowl, but former coaches rave about Coryell as a pioneer of the modern passing game. As Tony Dungy told SI.com in 2010, "If you talk about impact on the game, training other coaches—John Madden, Bill Walsh, Joe Gibbs to name a few—and influencing how things are done, Don Coryell is probably right up there with Paul Brown. He was a genius.”

Howard Cosell

First true celebrity sports broadcaster; brought brash, caustic intellect to the MNF booth

The great Frank Deford sums up the inimitable Howard Cosell best. In a 1983 SI cover story, Deford wrote of the famed announcer: “In that jejune world up in the booth—high up in the booth—only one man possesses quickness and momentum. He is not the one with the golden locks or the golden tan but the old one, shaking, sallow and hunched, with a chin whose purpose is not to exist as a chin but only to fade, so that his face may, as the bow of a ship, break the waves and not get in the way of his voice. For as long as he speaks, whoever rails at Cosell’s toupee isn’t seeing the bombs for the silos.”

Howard Cosell may be best known for his storied relationship with Muhammad Ali, but the announcer’s impact on professional football might be as critical as anyone in the sport’s history. As the color voice of Monday Night Football for 14 years, from its inception in 1970 until 1983, it was Cosell who became such a celebrity that he’d be trailed home by hundreds of fans after games. Through his prominence, Cosell ushered the NFL into prime time, into the living room of houses all over America, with his caustic wit and authoritative voice.

Cosell was so polemical, so much ingrained in the culture of sports, that he was once voted both the most popular and the most disliked sportscaster in America. From boxing to the Olympics to Hollywood, Cosell was ubiquitous in American culture for decades. But his prominence was greatest when he was in the booth every Monday night on ABC. For years, Cosell’s staccato voice was synonymous with the NFL—whether you loved him or hated him.

Al Davis

Iconoclastic Raiders coach and owner who challenged league orthodoxy

Al Davis was truly one of a kind, the only person in NFL history to serve as a personnel assistant, scout, assistant coach, head coach, general manager, commissioner and owner. After an itinerant early career that took him from Adelphi College to the U.S. Army, from the Baltimore Colts to the University of Southern California, Davis entered the AFL ranks as an assistant for the Chargers. When he became Oakland’s head coach in 1963—the team’s fourth in four seasons—winning was “completely foreign to anything the Oakland Raiders have ever done before,” SI’s Walter Bingham wrote of the franchise that had a 9-33 record in its first three seasons. “But,” Bingham continued, “now Al Davis arrived.”

Those words proved prophetic, as Davis would bring his “Commitment to Excellence” mantra to the franchise and come to coin his trademark phrase, “Just win, baby.” After briefly leaving the team in 1966 to become the commissioner of the AFL, Davis returned to the Raiders the following year as general manager and owner, and he soon hired John Madden as coach. Under Davis’s leadership, Oakland would win three Super Bowl titles, and would have just one losing season from 1965 to ’85.

Known as a caustic renegade, Davis was one of the first outspoken owners in sports. He constantly feuded with the league and was in large part responsible for the emergence of the AFL as a true competitor of the NFL. He sued the league to move the Raiders to Los Angeles in the ’80s, only to later move them back to Oakland, presaging the the era of franchise movement. He was also known as an early champion for diversity in the NFL, hiring the first head coach of Hispanic descent (Tom Flores) and the first African-American head coach (Art Shell), refusing to place his team at segregated hotels on road trips and encouraging his employees to scout and draft players from historically black colleges and universities.

Upon his death in 2011, SI’s Richard Hoffer wrote, “Davis not only dominated the game with his madcap misfits but also wrote the rules by which everyone, enemies included, ended up playing.”

Eddie DeBartolo

49ers owner whose player-friendly approach lay the foundation for a dynasty

Eddie DeBartolo had this wild notion that instead of treating NFL players like cogs in a machine, you could treat them like humans, and might actually create an atmosphere conducive to winning as a team owner. Crazy.

Under DeBartolo’s ownership, beginning and 1977 and stretching until 2000, the San Francisco 49ers went to the playoffs 16 times, played for the NFC title 10 times and won five Super Bowls. Two years after purchasing the team, DeBartolo tabbed Stanford coach Bill Walsh for the job with the Niners. After Walsh left, DeBartolo kept it rolling with George Seifert for two more world championships.

SI called DeBartolo “the best owner in pro sports” in a 1990 profile that detailed how generous he was to his players, staff and others. Just one example: When a player was injured in a road game and stayed behind for treatment, he’d arrange for a private jet to bring the player back home. “Thank god Eddie didn't have to cut guys,” Bill Walsh said in that 1990 profile, “or they'd never have gotten cut.”

DeBartolo’s ownership ended at the turn of the century when he became embroiled in a Louisiana casino scandal. He pleaded guilty to failing to report a felony in relation to efforts made to secure a casino license. Banned from the NFL for a year, DeBartolo ultimately sold his stake in the team to his sister, Denise DeBartolo York, and continued working in the family shopping center business. Still, the 2016 Hall of Fame inductee remains at the heart of the 49ers: As famed receiver Dwight Clark battled ALS in his final years, DeBartolo flew Clark’s former teammates to his Montana ranch to celebrate, reminisce and say their farewells. “Everyone knew in the ’70s and ’80s that when Mr. DeBartolo owned the team, that was the team to be on,” lineman Kevin Gogan told SI’s Chris Ballard in 2018. “And I finally got a taste of it later in my career. I don't care how much money you make, if you treat guys with the utmost respect, you're going to get so much more out of them.”

Mike Ditka

Revolutionary pass-catching tight end and iconic Bears coach who gained massive mainstream fame

Mike Ditka has spent six decades in the football spotlight, the living embodiment of the game’s tough-guy image. Legendarily competitive as a three-sport star at fabled Aliquippa (Pa.) High and Pitt (where he would punch out not just opponents but teammates whose effort he questioned), he was drafted by the Bears in the first round, fifth overall, in 1961. A fast and bruising proto-Gronkowski, Ditka revolutionized tight end in the pros: His 1,076 receiving yards as a rookie were most ever at the position, and his 248 catches in his first four seasons—including 75 in Chicago’s 1963 championship campaign—were unmatched until the likes of Kellen Winslow and Ozzie Newsome arrived two decades later. Ditka was All-Pro twice and made the Pro Bowl in each of his first five seasons.

After a contract dispute with Bears owner George Halas (whom he famously said “throws nickels around like manhole covers”), Ditka spent two years in exile with the Eagles, then joined Dallas, where he won a Super Bowl as a platooning tight end under Tom Landry. After retiring, he joined Landry’s staff as special teams coach, and though you’d be hard-pressed to find two men more different in temperament, Ditka credits the stoic Cowboys coach for rescuing his career and his reputation.

In 1982 Halas hand-picked Ditka to take over the woeful Bears, and over the next few years he remade the franchise in his fiery, throwback image. Ditka cleaned house, set the tone by breaking his fist with a locker punch (then telling his troops to go out a “win one for Lefty”) and held the wheel as Walter Payton ran rampant and Buddy Ryan’s defense rose to dominance. Many consider Ditka’s ’85 Bears, wildly loaded with talent and personalities, the greatest team in league history.

That feverish high proved unsustainable—Ryan left, Ditka’s teams floundered in the playoffs, and he was fired after a 5-11 season in 1992. Nor could he recapture the lightning in three years with the Saints, where the hallmark of his coaching tenure was trading away his entire 1999 draft to select Ricky Williams.

No matter. Ditka had become a folk hero in Chicago and beyond, immortalized in the Saturday Night Live sketches in which four worshipful superfans in aviator sunglasses and fake mustaches waxed hyperbolic about Da Bears and Da Coach. Ditka has worked as an analyst for NBC and ESPN, and he flirted with a run at the 2004 U.S. Senate seat that would be won by Barack Obama. It’s probably best he didn’t make it to Washington—if only for the sake of the lockers in the Senate gym. “I wasn't always the best, but nobody worked harder,” Ditka told SI in 1985. “One-on-one. You and me. Let's see who’s tougher. I lived for competition. Every game was a personal affront. Everything in my life was based on beating the other guy.”

Judge David Doty

Federal judge who oversaw league/union labor relations and opened the door to free agency

For more than two decades, Judge David Doty ruled over owner-player relations from his seat on the U.S. District Court for the District of Minnesota. During a six-year stretch beginning in 1987, Doty presided over the contentious back-and-forth between NFL owners and the players union over free agency, eventually threatening to draw up his own solution if the two sides could not come to terms. The result shaped the NFL as we know it.

For decades, owners held the power in labor dealings with players. That started to erode in the ’70s, when the union began to challenge the league through antitrust litigation, choosing the federal court in Minneapolis as the venue. Doty, an ex-Marine, was appointed to the bench by President Reagan in 1987, and a year later he made his first ruling in favor of the players (it was overturned on appeal). In ’92 he presided over the bench trial that found “Plan B” free agency a violation of antitrust law, and soon after, in the Reggie White case, he threatened to impose his own version of free agency if the league and the union could not settle on one; the NFL buckled, and the consequent collective bargaining agreement ushered in free agency and the salary cap. Because the CBA included a consent decree, Doty’s court retained jurisdiction over NFL labor matters through the life of the agreement. The NFL’s fears that such a ruling would ruin pro football proved unfounded, of course; over the next two decades the league saw unprecedented success and revenue growth.

Doty’s court was final arbiter in NFL-NFLPA disputes up until the dissolution of the CBA in 2011. His final involvement in an NFL matter came in 2015, when, true to his player-friendly reputation, he reversed Adrian Peterson's suspension for alleged child abuse and chided Roger Goodell. “I’m not sure the commissioner understands there is a CBA,” Doty said at the time.

Tony Dungy

First black Super Bowl-winning coach, with an extensive and influential coaching tree

Few men have brought as much dignity and grace to their profession as Tony Dungy has to coaching. A three-year backup defensive back with the Steelers and 49ers, Dungy joined the NFL coaching ranks in 1981, instructing DBs in Pittsburgh and then Kansas City until 1991. He became Dennis Green’s defensive coordinator in Minnesota in 1992, and then Tampa Bay’s head coach in 1996, where he turned the struggling franchise into a regular playoff team. In 2002, one year after Dungy was dismissed from Tampa, the Bucs hoisted a Lombardi trophy with the team he built. Dungy, in the meantime, had been hired by the Colts, who went on to double-digit wins and the playoffs in each of his seven seasons there. His coaching peak came in 2006, when his Colts won a Super Bowl against a Bears team coached by Lovie Smith, one of seven former Dungy assistants who went on to become a head coach.

Dungy is as highly regarded for his work away from football as he is for his record, extensive coaching tree and influence on the game. He is invested in his Evangelical faith, personal and group mentorship and extensive civic involvement. He is also a television personality, noted author and motivational speaker. His work in these fields are significant, but in a series like this one, it should not distract from Dungy’s impact on the game, which was—and still is—monumental. His Tampa 2 scheme in the late ’90s and early 2000s revolutionized how people look at defense. Dungy took a traditional Cover 2 zone defense but had the middle linebacker drop deep down the center of the field, running with the innermost vertical receiver. This increased the athletic demands placed on linebackers (everyone sought the next Brian Urlacher, who filled the Tampa 2 “Mike” backer duties better than anyone else), and had spillover effects that changed how other defensive schemes were constructed. In the falling dominoes of pro football strategy, this forced changes in the design of passing offenses. Dungy brought a beautiful simplicity to the game.

John Elway

Generational talent who forced a draft trade to Denver; first person to win the Super Bowl as a QB and GM

While he would later be known as one of the greatest quarterbacks in history, John Elway started his NFL career by flexing all the power a prized collegian has at his disposal, when he refused to sign with the Baltimore Colts, the team that selected him No. 1 overall in the famed 1983 draft. Elway, a two-sport star at Stanford, threatened that rather than sign with the Colts, he would play for the Yankees, who’d chosen him in the second round of the MLB draft two years earlier. In a bind, the Colts traded Elway to the Broncos for two veteran players and a first-round pick—reshaping the landscape of the league for the next two decades.

In Denver Elway became one of the most prolific passers—and running quarterbacks—in league history, the first ever to pass for more than 3,000 yards and rush for more than 200 yards in the same season seven consecutive times. But what is remembered most in Elway’s career was his penchant for heroics, including 31 fourth-quarter comebacks. There were the two against Cleveland in AFC title games, most famously “The Drive” in January 1987, when Elway took the Broncos 98 yards in the waning moments to send the game to overtime. Yet for years Elway fought the label of being one of the greatest quarterbacks who had never won a Super Bowl. That was until he led Denver to back-to-back Lombardi trophies in the final two seasons of his career, a fitting swan song for the legendary passer and Broncos icon.

Elway was not done, though, as in 2011 he was named general manager of his former team. And while so many retired athletes have failed when moving to executive positions, Elway thrived. As GM, he built a roster that took the Broncos to two Super Bowls and in 2016 he earned the franchise its first title since he was behind center. The triumph made Elway the first man in NFL history to win a Super Bowl as a quarterback and a general manager, an achievement that will be hard to match.

Brett Favre

Most durable quarterback ever, with a tumultuous life story that captivated America

On the heels of a gilded age of NFL football that transformed a handful of clean-shaven, golden-armed quarterbacks into Sunday staples and household stars, came Brett Favre, and the league was never quite the same again.

A rambling, freewheeling passer from Southern Mississippi known as much for gutting through hangovers as for his golden arm, Favre nabbed a far-flung chance at becoming a starting quarterback in both college and the NFL and never gave it up. When he was dealt to the Green Bay Packers from Atlanta in 1992, he netted a higher return (first-round pick) than his initial draft slot (second round), this despite throwing only four passes in Atlanta (none complete, two picked off).

In his first season in Green Bay, with the Packers steeped in an extended spell of irrelevance, Favre took over in Week 2 of ’92 for Don Majkowski and never let go. So began a stretch of 17 straight seasons in which Favre would play all 16 games, a stunning display of dedication and pain tolerance.

Favre, who admitted he did not know how to identify a nickel defense, was almost the anti-Montana or Manning. He was blunt, charismatic and, in many ways, grew up in front of America. Amid his push to become the league’s all-time passing leader (he was later overtaken by both Peyton Manning and Drew Brees), Favre battled through addiction and the death of his father, which was immortalized in an epic Monday night performance known simply as the “Dad Game.” He finished his career with typically eventful—even weird—stints in New York with the Jets and Minnesota with the Vikings. Never one to willingly give up his place, Favre made the Packers’ transition to Aaron Rodgers awkward—Favre retirement speculation was an annual pastime in Green Bay; he finally did “retire” after the 2007 season, but later said he felt pressured to do so by management, and returned to play another three seasons elsewhere, motivated through his last days in the pros by the perceived Packers slight. In his age 39 through 41 seasons, Favre completed 65.4 percent of his passes, threw 66 touchdowns to 48 interceptions and took the Vikings to within one play of the Super Bowl. As usual, Favre also took a boatload of sacks, and only after the final one—a takedown by the Bears’ Corey Wootton late in the 2010 season that left Favre briefly blacked out—did he fail to come back. It was the last play of his career.

The rift with the Packers lasted seven years. Finally in July 2015 he returned to Green Bay to be inducted into the team’s Hall of Fame—and was met by a sold-out crowd of 67,000 fans at Lambeau Field for a heartfelt reconciliation. Said Favre afterward, “It was like I never left.”

Peter Gent

Receiver who parlayed a brief Cowboys career into the novel/film North Dallas Forty, the Ball Four of the NFL

“Every time I try and call it a business you say it’s a game, and every time I say it should be a game you call it a business.” That quote, a heated barb flung by a pro football player at his coach toward the end of the novel North Dallas Forty, conveys the divide at the heart of Peter Gent’s fictionalized 1973 account of his experience in the NFL. A basketball player at Michigan State, Gent attended a tryout with the Cowboys in 1964, won a job and spent five seasons as a receiver with Dallas, splitting time as a No. 2 opposite the great Bob Hayes. Increasingly hobbled by injury (and disillusion) over those five years, Gent was traded after the 1968 season to the Giants, who waived him in the summer of ’69. It was then that he turned to writing, to attempt to capture what he’d been through.

North Dallas Forty, published in 1973, was one of a handful of books by players around that time—notably Out of Their League, the memoir by onetime Cardinals linebacker Dave Meggyesy, and major league pitcher Jim Bouton’s Ball Four—that dispensed with the anodyne, Chip Hilton-style depictions of American sports, pulling back the veil on the real, lived experience of professional athletes. In North Dallas Forty, Gent and his teammates, confronted by football’s visceral brutality, cope through booze, pot, pills, sex and various aberrant behaviors. The thinly veiled characterizations of Cowboys players and staff—Don Meredith, Tom Landry, Hayes and others are easily identifiable—caused a stir upon the book’s publication, but what lifts Gent’s novel above the level of salacious tell-all is its wider ambition.

Playing out amid the turmoil of America in the ’60s and ’70s—Vietnam war protests, racial strife, assassinations, Cold War fears—Gent aimed for a larger critique of the society that each Sunday embraced pro football’s dehumanizing violence, its infliction of pain for the public’s pleasure. The NFL, in Gent’s eyes, stood as a microcosm of the conflicts playing out in America in his era, the unpredictable, free-spirited individual in perpetual battle with authoritarianism and conformity, the team and the NFL standing in for the machine that crushes independent spirit and compels rigid adherence. Needless to say, the Cowboys did not appreciate the look.

Gent contributed to the screenplay for the 1979 movie, which smoothed out some of the novel’s rougher edges but pulled no punches in its depiction of the way in which pro football uses up and spits out players. If the Sabols, through NFL Films, glorified football’s grandeur, Gent and those like him showed fans the other side—vicious, abrasive, impersonal, demeaning. The paradox is that through it all, Gent loved the game. “I felt more in one Sunday afternoon than I did later on in whole years,” he wrote in the foreword to the 2003 edition. Like the fans, and the society as a whole, Gent embraced the contradictions inherent in that love. “There’s no greater display of everything that’s magnificent about sport in America,” he wrote, “and everything that’s wrong with culture in America.”

Frank Gifford

Clean-living Giants back who missed nearly two seasons after Bednarik’s knockout; later anchored MNF

Frank Gifford spent 12 years as an effective multipurpose weapon with New York Giants and 27 as a play-by-play announcer and commentator for ABC’s Monday Night Football. He began his NFL career as a shifty running back and ended it as a clutch receiver, making eight Pro Bowl appearances and playing in five NFL championship games, winning a title in 1956, when he was named league MVP. In a 1960 game against the Eagles, Gifford took a brutal high hit from linebacker Chuck Bednarik, leaving him motionless on the field. Gifford retired afterward, so damaging was the hit and so lengthy the recuperation period. But 18 months later, he rejoined the Giants, this time as a receiver.

By the time Gifford retired from the NFL for the second time in 1964, the league’s popularity was rising, and Gifford was a national star, posing for ads and hanging out with New York celebrities. Blessed with good looks and charm, Gifford transitioned seamlessly from the field to the booth at CBS, and then joined Monday Night Football in 1971 for the show’s second season, where he became the level-headed straight man in the booth to the louder and much more dramatic Howard Cosell and Don Meredith, as well as a host of other partners through the years.

Gifford died at age 84 from natural causes, and soon after, the family revealed he had chronic traumatic encephalopathy, the degenerative brain disease that can only be diagnosed posthumously and that has been found in numerous former football players. The family revealed the CTE diagnosis with the hope that more attention would be paid to medical research linking football and traumatic brain injuries.

Sid Gillman

Pioneer of the modern passing game

It’s not so much Sid Gillman’s accomplishments as a head coach—five AFL Western Division titles with the Chargers, an AFL Championship in 1963, Pro Football Hall of Fame enshrinement in 1983—as the way he went about achieving them. As Al Davis, perhaps Gillman’s most noted disciple, once said, "Sid Gillman brought class to the AFL. Just being part of Sid’s organization was, for me, like going to a laboratory for the highly developed science of organized football.”

Gillman was the first to see offensive football from a predominantly aerial, vertical standpoint. He implemented a downfield-attacking offense with the Chargers that became the genesis of the modern game. His 1963 AFL title—the Chargers’ only league championship ever—was a master class, as San Diego stymied the Boston Patriots 51-10, gaining 610 yards on offense, with schemed motion to negate the Patriots’ blitzing. Gillman titled his game plan that week “Feast or Famine.”

Game-planning was Gillman’s forte. He revolutionized the endeavor by studying film. He and Paul Brown could cut and splice game film (using scissors) to analyze opponents’ strategies, and Gillman insisted on filming all of his practices so that he could later watch and grade players. He was conducting this exercise as early as the ’50s, when he was the head coach at the University of Cincinnati. In ’53, in fact, the NCAA ruled that the practice gave Gillman’s team an unfair advantage, not because the Bearcats would study film before the game, but rather, because they’d do it during the game, at halftime in the locker room.

Gillman became the L.A. Rams’ head coach in 1955. He went 26-21-1 before a 2-10 season in 1959, upon which he was fired. The cross-town Chargers of the new AFL hired him the next year—among the staffers Gillman brought in were Chuck Noll as defensive assistant and Al Davis as receivers coach—and he went 10-4 his first season and 12-2 in his second. Over his 11 years with the Chargers, Gillman was 86-53-6.

In 1992, SI’s Paul Zimmerman wrote, “The Gillman system spread like branches of a tree throughout the world of football. His assistants on those early Chargers, Chuck Noll and Jack Faulkner, took it to Pittsburgh and Denver, respectively, then Faulkner took it to the Rams as their special assistant coach. Al Davis and Al LoCasale took it to Oakland, where it rubbed off on [Bill] Walsh. Kay Stephenson, Dan Henning and Don Breaux all had been quarterbacks for Gillman at San Diego, and his ideas followed them to Buffalo and Atlanta and San Diego and Washington. As head coach at Miami of Ohio and Cincinnati, Gillman had groomed such future coaches as Bo Schembechler, [Paul] Dietzel, Bill Arnsparger, Johnny Pont and Ara Parseghian.” And that’s just the beginning of the Gillman tree.

Pete Gogolak

NFL’s first soccer-style kicker

A Hungarian immigrant who came to the U.S. only to find that soccer barely existed here, Pete Gogolak ended up applying his love of “football” to the American version, and changed his adopted country’s pastime.

The first prominent kicker who approached and contacted the ball like a soccer player—from the side, with the instep—Gogolak turned heads during an era of rotund linemen/placekickers chugging up to the football and hitting it square with their toe. And there was a demand for his services.

Famously, Gogolak spurned the AFL’s Buffalo Bills after his second professional season, when his request to double his salary to a whopping $20,000 per year was denied and he crossed over to the NFL’s New York Giants. The move shattered what had been a wall between the rival leagues, eventually leading to a signing frenzy from deep-pocketed owners on both sides of the aisle. It was easier, then, to bring both leagues under one umbrella than to continually fight with another entity not bound by the same free-agent rules.

Setting off a placekicking revolution and serving as the catalyst for the eventual merger of the NFL and the AFL, the most important event in pro football’s sporting ascendance? Not bad for a guy from Budapest.

Roger Goodell

Commissioner during the league’s most tumultuous decade

Roger Goodell’s directive from owners when he assumed the job of commissioner in 2006 was to take a product that had been forged through years of elbow grease, trials and tribulations, and monetize it. Given the league’s soaring revenues over the course of his commissionership, for that alone he will undoubtedly be seen as one of the most significant figures in NFL history.

But Goodell’s legacy may end up being one of the most complicated of any prominent American sports figure. A lifer in the league office, Goodell almost immediately encountered a wrecking ball of issues when he took over that left the NFL looking flat-footed and slow to come around to modern times. Growing understanding of head trauma and its impact on retired players caused a seismic shift in the way people looked at the game. There were the Bountygate and Deflategate scandals. The was the lockout. The replacement ref fiasco. The Richie Incognito-Jonathan Martin case. There were Michael Vick and Ben Roethlisbergrer, Ray Rice and Greg Hardy. Adrian Peterson. Tyreek Hill and Kareem Hunt. There was a quarterback crisis. There is the minority coaching crisis, the wobble in television ratings, and worries over the “in-game” experience. There is legalized gambling, E sports and other myriad changes to the world and society to come. Goodell has been there throughout all of the tumult.

Given the fact that so many off-field issues overshadowed what would have been a golden age of football, it’s hard to imagine that Goodell does not have his regrets. However, the league is not without accomplishments during his time. For one, a legion of owners has held him in high regard, not only for his ability to absorb criticism that might otherwise be directed at them, but for the way he has advanced their personal interests in the face of obstacles and opposition. Stadium deals are more lucrative. Television deals are more lucrative. In any given year, almost all of the most-watched programs in America are NFL broadcasts. Ultimately, Roger Goodell’s legacy may be defined by his ability to keep it that way.

Otto Graham

Seven-time champion (AAFC, NFL) as Browns quarterback

The Browns are one of two non-expansion teams, with the Lions, that have never appeared in a Super Bowl. But long before they were known for their ineptitude, the Browns were a very, very successful team. Northwestern halfback Otto Graham was the first player signed to the brand-new Browns franchise (of the upstart All-American Football Conference) in 1946, and team co-founder and coach Paul Brown converted him to quarterback. Graham quickly took to the T-formation and led Cleveland four straight AAFC championships.

When the Browns were absorbed, along with the 49ers and Colts, by the NFL—assumed to be a more competitive league—in 1950, commissioner Bert Bell wanted to give them an immediate challenge. He scheduled their first game against the two-time defending champion Philadelphia Eagles. Graham’s first pass in the NFL was a touchdown, and Cleveland ended up crushing Philly 35-10, with Graham throwing for 346 yards and three touchdowns. The test was passed.

Graham led the Browns to the championship game in each of their first six seasons in the NFL, winning in 1950, ’54 and ’55, after which he retired—meaning he played in a league championship game every year of his pro career. Graham also never missed a game over those 10 seasons. Any debate about the most accomplished quarterbacks in league history has to include him.

Red Grange

1920s college star whose move to the NFL lifted the profile of the pro game

Harold “Red” Grange was the first player to drop out of school to turn professional. In 1925, when Grange left the University of Illinois to play with the Chicago Bears, the NFL was a pale imitation of the college game and struggled to attract crowds. Grange was the college game’s biggest star, a three-time All-America running back at Illinois dubbed the “Galloping Ghost” by reporters. So, before the 1925 college football season, C.C. Pyle, a movie theatre manager in Champaign, Ill., approached Grange with a proposition. How would he like to earn $100,000? Pyle orchestrated an unprecedented contract with the Bears that would bring the college star to the NFL for a 19-game, 66-day cross-country tour during the winter of 1925-26. With the contract, Pyle became the first real football agent, and Grange received a cut of the gate receipts for all the games played on the barnstorming tour. In his first eight games as a pro, Grange played before an estimated 200,000 fans, including upwards of 70,000 at the Polo Grounds against the Giants. Babe Ruth was there to watch, as were some 100 sportswriters. His star power boosted pro football and made it a sport to watch. Grange’s sudden shift from college to the pros also had an impact on the relationship between colleges and the NFL, ultimately leading to the creation of the NFL draft.

Grange made $20,000 when the Bears played Philadelphia during that tour, and another $20,000 when they played New York, amounts unheard of in an era when most players hardly made $100 per game. In 1926 Grange and Pyle formed a rival league to the NFL, and Grange played two seasons for the New York Yankees of the American Football League. In ’27 he suffered a serious knee injury and was never the same runner. Still, rejoining the Bears in ’28, he played for six more seasons, winning championships in 1932 and ’33 and twice being named All-Pro. Like other sports stars of his (and our) time, he capitalized on endorsement deals and appeared in Hollywood movies. Grange was a star of his era on par with Ruth and Jack Dempsey, and while his pro career never came close to matching what he’d done in college, his simple decision to get paid to run the ball had a colossal impact on the evolution of the sport.

Mean Joe Greene

Anchor of Pittsburgh’s Steel Curtain defense and star of a classic Coke commercial

The Pittsburgh Steelers of the ’70s won four Super Bowls in six years, sent nine players to the Hall of Fame and set the standard for NFL dynasties in the Super Bowl era. It all started with Joe Greene.

Steelers scouts were split on Greene in the lead-up to the 1969 draft—so overpowering was he at North Texas State that they found it hard to measure his true talent, or his passion. But new coach Chuck Noll had no doubts, taking Greene with his first pick (fourth overall), coaching him up and building a generational defense around the 6'4", 275-pound defensive tackle. Greene terrorized quarterbacks and ball-carriers throughout the decade, making the Pro Bowl in each of his first 11 seasons, earning four All-Pro nods and winning Defensive Player of the Year twice. Noll’s specially designed “pinch” defense aligned Greene at an odd angle to the center, taking advantage of his unique blend of strength and nimbleness to dominate the middle of the line. In Pittsburgh’s first Super Bowl win, the Steelers held the Vikings offense to 17 rushing yards and zero points; Greene had an interception and a forced fumble and recovery.

Plagued at times by neck trouble, as in the playoffs in January 1976, Greene was sometimes “more of a mental deterrent than a physical obstacle” to opponents, as SI’s Mark Mulvoy wrote. Indeed, his very presence lifted Pittsburgh—the team and the city—and commanded both fear and respect. Said Lynn Swann in a 1975 SI profile of his teammate, “Last year somebody clipped him and he stomped on the guy’s head. The referee ran up to him, says, ‘Mr. Greene!’ Not ’75,’ like he’d say to anybody else. ‘Mr. Greene!’” About that nickname: Greene said it arose during college when North Texas State fans started calling their defense the Mean Green and naturally shifted it over to their big defensive lineman. But Greene was known on occasion to break a few teeth, twist a foe’s a helmet off or supply a strategic kick. “I'd grab a face mask only in a fit of anger,” he told SI’s Roy Blount in that ’75 profile. “Uncontrolled anger is damn near insane.”

So it was a stroke of genius to cast Greene against type in one of TV’s most memorable commercials. A battered warrior limping to the locker room, Greene begrudgingly takes a Coke from an admiring kid, and tosses the awestruck fan his jersey return. The ad, which aired during the baseball playoffs in 1979 and on the 1980 Super Bowl telecast, won a Clio Award and has been named one of the 10 greatest commercials in history. “It pulled the mask off the gladiator,” said writer Gary Pomerantz, calling it, “a monument of brisk, effective, dramatic storytelling.”

It also changed Greene’s life. “I was suddenly approachable,” he said in 2014. “Little kids were no longer afraid of me, and older people, both women and men, would come up and offer me a Coke.”

George Halas

League co-founder; owner, coach and patriarch of the Bears

Three-time coach of the Chicago Bears, an eight-time NFL champion, captain in the Navy, outfielder for the New York Yankees—there are few who could claim a more significant footprint across the field of athletics than George Halas.

But it was his time as the coach and owner of the Bears that will leave the most lasting impact. The NFC championship trophy is still named in his honor. Like Paul Brown, Halas was early to the use of film and the deployment of assistant coaches to help him see the game. He would go on to coach 497 games, winning 318 of them.

He was from a golden age of professional football and, in its infancy, had to make decisions for the betterment of the fledgling league and sport rather than to deepen the financial interests of the owners. Halas was an early voice in the movement to charge fans admission and to use that revenue to compensate players. He was a fixture in all aspects of the budding game, including in the communications department and sales. He was also a proponent of sharing revenue to aid smaller markets and the creation of a draft, which would prevent the larger cities from building a singular pipeline from the collegiate game. His oldest daughter, Virginia Halas McCaskey, remains the principal owner of the team, keeping the legendary Halas name alive, as a direct link from the Hupmobile showroom in Canton where her father drew up plans for a pro football league to the powerhouse that dominates the American sports landscape today.

Scott Hanson and Andrew Siciliano

Hosts of transformative (and rival) Red Zone broadcasts

It’s remarkable how much of the NFL’s growth over its first 100 years is a direct result of changes in the media that affect how fans consume the game. With that in mind, it’s hard to understate the importance of DirecTV’s Red Zone Channel and its spin-off NFL RedZone on the modern fan experience. It’s tempting to credit the innovator who first dreamt up the concept of a live, commercial-free, whip-around highlight show on 17 glorious Sundays each year—a News Corp. exec named Eric Shanks hit on the idea after seeing a whip-around soccer show in Italy—but Scott Hanson and Andrew Siciliano have become the platform’s avatars, representing broadcasts that revolutionized the way so many viewers spend football Sundays.

The 1990s were not that long ago, but think about how NFL fans followed their favorite players and teams back then. There were fewer prime-time games, and viewers relied on occasional “game breaks” and evening highlight shows for a taste of what was going on. If you didn’t live in your favorite team’s market, good luck getting an update.

Now fans can essentially watch up to 13 Sunday afternoon games in one full helping. We can keep tabs on fantasy teams and parlays, every touchdown, and anything else deemed highlight-worthy. Older fans can only wish they were able to see the careers of Jerry Rice, Barry Sanders or Sammy Baugh in the octobox.

Here’s one last way to think about the incredible tonnage of air time: If you watched John Madden call one game a week for 30 years, you could spend as many cumulative hours on your couch watching Siciliano or Hanson narrate live game action in half as many years. They have educated and influenced an entire generation of football watchers, and done it all without ever teasing what would come up after the next commercial break.

Bob Hayes

Olympic 100-meter champ who brought mind-blowing speed to the NFL game

The first of the field-stretching receivers, Bob Hayes remains the only person to win both Olympic gold in track and field and a Super Bowl. A football star at Florida A&M, Hayes moonlighted as a sprinter, setting college records at historically black school meets across the South but rarely gaining invites to major events at barely segregated large universities. When Hayes was chosen to represent the U.S. at the 1964 Tokyo Olympics (where he would win gold in the 100-meter dash and the 4x100), President Lyndon Johnson was moved to ask his football coach, Jake Gaither, if Hayes could have some time off from the gridiron. “But Mr. President,” Gaither said, “Bob is a football player. He just happens to be the World’s Fastest Human.”

The man with that lofty nickname was drafted by the Cowboys in ’64 (one spot ahead of Wichita State lineman Bill Parcells) and played 10 seasons for Dallas. An immediate difference-maker, Hayes topped 1,000 yards and led the league in TD receptions in each of his first two seasons, and was twice named All-Pro. In 1970 he averaged an eye-popping 26.1 yards per catch, a figure that no receiver since has matched.

Hayes heralded a wave of sprinters entering the NFL, but his biggest impact was on the shape of defenses. Since he destroyed man-to-man and rudimentary zone coverages, “coaches came up with a double zone to try to control him,” SI’s Paul Zimmerman wrote. “A cornerback would play him tight as he came off the line—in those days defenders could do anything they wanted to a receiver, except grab and hold—and another defensive back would pick him up deep. Or coaches would assign the deepest defensive back, usually the free safety, to make sure he stayed behind Hayes, which opened up vast areas underneath. No other player caused that kind of strategic overhaul of the defensive game.”

Hayes hit hard times in retirement, and the 10 months he spent in jail on a drug trafficking charge likely delayed his Hall of Fame induction. He died from kidney failure in 2002 at age 59, having finished his degree in education at FAMU. In 2004 the Hall’s Seniors Committee nominated him for induction, but his candidacy failed the final balloting, after which Zimmerman resigned from the committee in disgust. Hayes finally earned induction in 2009.

Wrote former ESPN and Sports Illustrated scribe Ralph Wiley: "Oh, sure, there was speed in football before Bob Hayes. There just wasn't that much of it. Not track speed, warp speed, world-class speed, we-better-think-of-something-now jets."

Roy Hofheinz

Driving force behind the Astrodome, pro sports’ first indoor stadium

Before there was the ridiculous football space station in Dallas, or the opulent, robotic roof that opens and retracts over the Falcons in Atlanta, there was the Astrodome in Houston. And there was Roy Hofheinz.

The age of stadium design and, in many ways, the perception surrounding a team, a town and a franchise after a new stadium is built, changed when the former mayor of Houston pushed for and secured a concept that would change professional sports as we know it: a building that could, theoretically, host anything.

Hofheinz said he hit on the notion of a covered stadium after visiting Rome’s Colosseum, which featured retractable awnings to protect the crowd from the elements, and when a group that included Hofheinz was awarded a major league baseball franchise in 1960, it was realized that the city’s hot, humid summers would necessitate an indoor venue. Built at a cost of $35 million, the Astrodome opened in 1965 and was immediately heralded as a modern marvel. Dubbed “the Eighth Wonder of the World,” it boasted features that would become an essential part of the modern stadium experience, including high-end luxury suites, air conditioning, synthetic turf and an animated scoreboard that was the early forerunner of the massive video screens in every new stadium. It was the home of the Astros from ’65 until 1999, and the Oilers from 1968 until their move to Tennessee in 1997.

Before stadium building became another heartless money grab for the American plutocracy, Roy Hofheinz’s Astrodome was a genuine source of civic pride and national curiosity.

Paul Hornung

Packers golden boy who was suspended a season for gambling

Paul Hornung was so beloved, so revered and so consequential to the NFL that despite being suspended by the league indefinitely in 1963 for gambling on games (the cardinal sin of sports!), The Golden Boy’s reputation would go undamaged in the annals of the league. Hornung was one the first true superstars in the NFL, “a man who lived long nights, indulging a voracious appetite for excess,” as SI’s Tim Layden wrote in 2002. “He was Namath before Namath.” How big a star was he? When Hornung was called to active duty in the Army in 1961, coach Vince Lombardi privately petitioned President John F. Kennedy to grant Hornung a weekend pass to play in the New Year’s Eve NFL Championship Game game. The President obliged, and Hornung scored 19 points—a touchdown, three field goals and four extra points—in the Packers’ 37-0 victory over the Giants.

When the league suspended Hornung for betting on games, he accepted his punishment—but he also threatened Pete Rozelle by saying he’d go to the U.S. Senate and reveal the league’s much larger gambling problem. That incident was a mere blip on Hornung’s Hall of Fame career. He first rose to prominence as a quarterback at Notre Dame, where he won the Heisman Trophy and earned his Golden Boy nickname for his blond locks and the Golden Dome of South Bend. Drafted first overall by the Packers in 1957, Hornung switched to halfback (he also did some placekicking) and led the league in scoring in three straight seasons; in 1960, in just 12 games, his 176 points set an NFL record that stood for 46 years. The following year he was named league MVP.

On a Packers dynasty that dominated the NFL for a decade, a team that was stocked with Hall of Famers at every position, it was Hornung who stood out as the most important member. “The Packer team takes its cues from Hornung, a natural leader,” wrote SI’s Tex Maule in 1964. After Hornung languished for his first two seasons, splitting time between halfback and quarterback, Lombardi turned him into the fulcrum of the offense, the point man for the famed Green Bay power sweep. During his career, Green Bay won four NFL championships and the first Super Bowl (though he sat it out with a pinched nerve), cementing his legacy as one of the most important figures in NFL history.

Lamar Hunt

AFL founder and patriarch of the Chiefs

The son of oil tycoons, Lamar Hunt was a football player in spirit but a budding sports entrepreneur in reality.

After becoming the first owner to bring professional football to Dallas (with the Texans of the AFL), Hunt was chased from his hometown after the NFL injected the Cowboys into the market and nabbed a majority of the fan base. However, that led Hunt to Kansas City, where he changed the team’s name to the Chiefs and presided over one of the league’s iconic franchises.