Bad ’Boys Could Use More Chad Hennings, Less Aldon Smith

No anger mismanagement. No bipolar disorder. No domestic violence. No assaults. No DWI charges. No vandalism. No performance-enhancing drugs. No arrests.

No substance abuse.

Only substance.

Once upon a time – before his risk-taking, oil-wildcattin’ DNA-fueled gambles on “talented-but-troubled” D-linemen Charles Haley, Alonzo Spellman, Dimitrius Underwood, Josh Brent, Greg Hardy, David Irving, Randy Gregory, Robert Quinn and now Aldon Smith – Dallas Cowboys owner Jerry Jones took a 1988 draft flier on Chad Hennings.

He was guaranteed not to play a down in the NFL for at least four years.

He was committed first and foremost – body, mind, heart and soul – to the United States Air Force.

He routinely piloted dangerous missions into active battlefields.

But considering the Cowboys’ lousy lineage of bang-for-their-baggage defensive linemen, Hennings was a surprisingly safe bet.

“Going straight from the war to football was the biggest challenge I’ve ever faced,” Hennings told me recently. “There are obviously traits that carried over, but it was just a whole new world. Physically. Emotionally. Mentally. Spiritually. I went from taking out the enemy to learning how to be teammates with Charles Haley and Michael Irvin.”

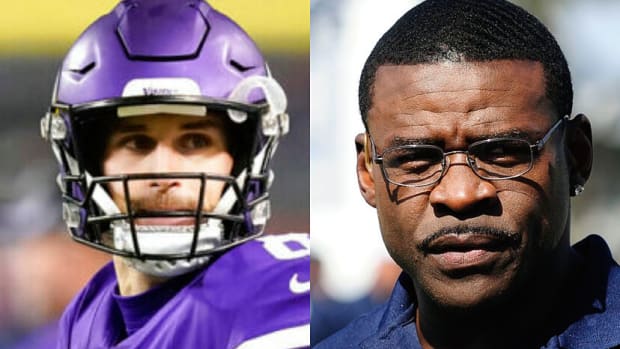

Despite a litany of legal troubles that have kept him off an NFL field since 2015, Smith last week earned a contract from Jones. As CowboysSI.com broke it down, the one-year, incentive-laden deal severely mitigates the Cowboys’ investment, with only $95,000 of a possible $4 million guaranteed. Five years ago, Smith was a Pro Bowl player with 33.5 sacks his first 16 games.

Maybe things have turned around. Here we read about Smith being 287 pounds of muscle, of his good deeds with military vets, of his new-found sobriety.

But indisputably, Aldon Smith has a past. And also, a past.

Unlike other Jones character-be-damned gambles on defensive players Pacman Jones, Tank Johnson and Rolando McClain, Hennings was all about the future. His only risk was the passage of time.

In 1987, Hennings won The Outland Trophy as college football’s best lineman.

In 1988, Dallas drafted him … in the 11th round.

“I’m not saying Chad’s another Roger Staubach,” newly minted Pro Football Hall-of-Famer Gil Brandt said at the time. “But we know first-hand that the character it takes in the military can translate to the football field. He’s got all the physical and mental tools to dominate in the NFL. We think he’s worth the risk. Hopefully someday it pays off.”

Hennings had it all - by not having anything.

None of the numerous entries on a rap sheet that helped – even foretold – the demise of Jones’ other high-profile, low-reward rolls of dice. Haley and his heinous history arrived in Dallas and helped the Cowboys win three Super Bowls. Most recently, however, it goes something like this: Smith (still suspended) was signed to help fill the void left by Quinn (suspended two games in 2019), who was signed to help fill the void left by Gregory (suspended numerous times), who was supposed to be a bookend to DeMarcus Lawrence (suspended four games in 2016).

It’s one thing to be the “Bad Boys” Detroit Pistons, throwing elbows, taking names and winning back-to-back championships. It’s another to be simply the Bad ’Boys, with a six-season streak of having at least one defensive player suspended, while not placing any defenders on the NFL 2010s All-Decade Team or winning anything beyond a Wild Card playoff game the last 25 years.

This is not to suggest that the Cowboys are the only team that employs behavioral risks, or that Jones has whiffed on every defensive lineman. Russell Maryland was a solid No. 1 overall pick. Despite arriving with a sketchy reputation, Tony Casillas contributed to a deep rotation that won three rings. And despite his infamous gaffes in the snow and the Super Bowl (and his own drug suspension), Leon Lett was a two-time Pro Bowl steal as a seventh-rounder. Lawrence and others have been very good players here.

This is also not a denial about something inherently savage, simplistic and, yes, screwy about the position. Sure, there are varying techniques and tricks, but defensive linemen are all about eradicating the blocker in front of you and hunting the football. It’s spawned legendarily intimidating players such as “Mean” Joe Greene, Ndamukong Suh, Warren Sapp, Deacon Jones and Jack Youngblood, who played in a Super Bowl with a broken leg. Defensive lines have inspired nicknames like the “Fearsome Foursome,” “Steel Curtain,” “Purple People Eaters” and, of course, “Doomsday.”

Hennings fit comfortably in the chasm between Hardy’s gun-covered futon and Dak Prescott’s pristine leadership. Worth the wait and void of stains, he finally arrived at Valley Ranch in 1992 as a 27-year-old rookie with superior athleticism, unprecedented character and not a single frayed wire.

“Every father wants their son to grow up to be Chad Hennings,” Troy Aikman once told me. “The guy’s straight outta Hollywood.”

Before he won three titles with “America’s Team,” he fought for America’s real team.

Fulfilling an eight-year military commitment with the Air Force, Hennings was stationed in England and piloting the A-10 “Warthog,” an aircraft designed to destroy tanks from three miles away via a machine gun that deployed 4,000 bullets per minute. He wound up flying 45 missions into Iraq, some to combat Saddam Hussein’s Republican Guard and others to escort C-130 aircraft that dropped supplies – tents, blankets, food – to refugees in the mountains fleeing the threat of deadly mustard gas dropped by their former dictator.

“I chose the Air Force because I wanted a unique experience,” Hennings said. “Wanted to challenge myself at a higher level as far as integrity and character. But a part of me also always wanted to play football.”

Though drafted by the former brain trust of Brandt, Tex Schramm and Tom Landry, Hennings became a Cowboy only after a tryout for Jones and Jimmy Johnson.

Said defensive coordinator Butch Davis after watching Hennings’ post-layoff workout, “We just had a No. 1 draft pick fall in our lap.”

He was 6-foot-6 and 290 pounds of discipline and deltoids. But the transition almost killed him. From the cool climate of England to the 100-degree heat and humidity of training camp at St. Edward’s in Austin, Hennings struggled to assimilate.

“I was losing 12-14 pounds of water weight during the morning workout,” he remembers. “Then trying to replenish before doing it again in the afternoon. And that was in addition to competing against the best offensive line in football with guys like Mark Tuinei, Nate Newton and Mark Stepnoski.”

Between the IVs, Johnson’s barking, unrealistic expectations and the spartan existence of St. Ed’s cinder-block dorms, Hennings grew frustrated and unconfident.

“I was like, ‘What the heck did I just do?’,” he said.

He was never fast enough to be Haley or Harvey Martin, or agile enough to be Randy White or Bob Lilly, but Hennings adapted well enough to be a front-line contributor to one of the deepest lines in NFL history. In nine years, he started 72 games, produced 24 sacks and won more jewelry than he’ll ever care to wear.

Since retirement in 2000, Hennings has raised two children now out of college, written three books about leadership, developed into a motivational speaker and launched a successful – surprise! – career in DFW commercial real estate.

“Business was always the wild card for me,” he said. “I knew being in the military or the NFL was what I did, but I didn’t want it to be who I was.”

The Cowboys could obviously use better players. Wouldn’t hurt to again try superior people.