Stewart faces several possible legal consequences after fatal accident

Former NASCAR champion Tony Stewart could face criminal charges, civil lawsuits and loss of endorsement deals in the aftermath of his race car striking and killing Kevin Ward, Jr. in a sprint-car race at Canandaigua Motorsports Park on Saturday night in upstate New York. The incident arose after Stewart’s race car clipped Ward’s race car, which then hit the outside wall, cut a tire and spun out, thereby prompting officials to issue a caution flag. The flag instructed the drivers to slow down. Ward then left his car, walked onto the track and seemingly tried to confront Stewart as Stewart’s race car approached his direction. Stewart's car then hit and killed Ward. Stewart and his representatives have described the incident as a tragedy and accident. The following analysis breaks down the potential legal consequences for Stewart.

SI Vault: Road Rage: Tony Stewart can handle everything -- except himself

Possible criminal charges against Stewart

The most serious legal consequences of Ward’s death are those grounded in New York criminal law. It is important to stress that Stewart has not been charged with a crime and that Ontario County sheriff Philip Povero unequivocally stated on Sunday there are “no facts in hand that would substantiate criminal intent from any party.” Povero also noted that he has consulted with Ontario County district attorney R. Michael Tantillo, who could seek a grand jury to evaluate whether to charge Stewart. Keep in mind, Stewart will not be charged unless law enforcement and prosecutors believe a jury would find his guilt beyond a reasonable doubt. Stewart should take relief from Povero’s declaration.

For two reasons, however, the absence of criminal intent in a sheriff’s estimation does not necessarily mean Stewart will avoid charges.

More: Who was Kevin Ward, Jr.?

First, a lack of pending charges does not mean that charges won’t be brought at a later date, including months or even years from now. The presence of a videotape is a crucial piece of evidence for law enforcement to review, as it provides a record of the event. Stewart’s clipping of Ward is also telling, because it could indicate that he wanted to scare Ward after Ward left his race car to confront Stewart. Driving close to someone as a way of frightening them could be considered reckless conduct, or at least an issue worthy of examination by a grand jury. Notably, Tyler Graves, a sprint-car racer who attended the race and who has been described as a friend of Ward, suggested to The Sporting News’ Bob Pockrass that Stewart acted with some degree of intent: “I know Tony could see [Ward] . . . When Tony got close to him, he hit the throttle.” If other drivers make similar comments, there may be increased pressure on Povero and Tantillo to pursue charges.

HARRIS: Accident leaves many questions that won't be answered

Along those lines, it is at least plausible that a grand jury could conclude that while Stewart did not intend to kill Ward – which, when accompanied by other elements, would constitute murder in the first degree – he may have engaged in conduct consistent with murder in the second degree. Under New York law, murder in the second degree entails acting with a depraved indifference to human life and recklessly engaging in conduct that “creates a grave risk of death to another person, and thereby cause the death of another person.” New York classifies murder in the second degree as an A-I felony, and it carries up to a life sentence and minimum of 15 years behind bars.

Report: Police say no sign of criminal intent; charges still possible

Second, “criminal intent” is not the only state of mind that could lead to criminal charges against Stewart. For instance, negligent homicide refers to accidentally causing the death of another through negligent conduct, such as reckless operation of a motor vehicle. Crucially, negligent homicide would not require that Stewart intentionally tried to kill Ward, only that he drove recklessly or carelessly. Such misconduct might include trying to scare — but not hurt — Ward. In New York, negligent homicide is a Class E felony and carries a maximum punishment of four years in prison.

Another plausible, though less likely, charge against Stewart is manslaughter in the first degree, which would necessitate that Stewart intended to cause Ward serious harm and in doing so killed him. A conviction would carry a prison sentence of up to 25 years. Manslaughter in the second degree, which carries a prison term of up to 15 years, would be appropriate if Stewart’s conduct in driving was deemed sufficiently reckless and connected to Ward’s death.

New York also has several criminal statutes related specifically to vehicular homicide. None of them appears relevant to Ward’s death. These statutes contemplate multiple deaths or injuries caused by a person’s driving, as well as excessive use of drugs or alcohol, or driving with a poor record. Stewart did not injure anyone other than Ward, and there is no reason at this time to believe that he was driving under the influence of alcohol or drugs, or that he faced prior charges related to his driving.

More: Stewart pulls out of Indiana dirt track race

Possible wrongful death lawsuit against Stewart and prospect of a settlement

While Stewart is poised to avoid criminal charges, he may not be so fortunate with civil litigation. Ward’s family could sue Stewart for wrongful death, which refers to negligently causing the death of another. A successful wrongful death lawsuit could lead to millions of dollars in damages, particularly since wrongful death damages are largely contingent on the decedent’s age and loss of future earnings. Ward was only 20 years old and he seemed to have a promising and possibly lucrative future as a driver. The statute of limitations for a wrongful death lawsuit in New York is two years, meaning Ward’s family has until Aug. 9, 2016 to sue.

Ward’s family would need to convince a jury that Stewart’s conduct was probably unreasonable and caused Ward’s death. Other drivers would be called to testify as experts and offer their views as to the reasonableness of Stewart’s conduct. Stewart himself could also be called to testify. His ability to invoke the Fifth Amendment to avoid answering questions would depend on whether the questions asked of him require him to admit that he engaged in criminal conduct.

In his defense in a wrongful death lawsuit, Stewart could argue that Ward’s own conduct played a crucial role in his death. After all, Ward clearly accepted some degree of safety risk by leaving his race car after it spun out of control. Drivers are discouraged from leaving their race cars during races unless their own safety is imperiled. Ward only elevated this safety risk by trying to confront or incite Stewart as Stewart’s race car approached on the track.

On the other hand, Ward exited his vehicle only after the caution flag was thrown and he must have had no expectation that Stewart’s race car would hit him or he obviously would not have waved his hands at Stewart. Moreover, if it is true that Stewart could see Ward, Stewart’s decision to drive so close to him and perhaps even increase his speed on the approach might prove damning in the minds of jurors. Expert testimony would prove crucial in an interpretive legal debate of what Stewart “should have done.”

Stewart, whose net worth reportedly exceeds $100 million, may try to avoid civil litigation by reaching an out-of-court settlement with Ward’s family. A settlement would constitute a contract between Stewart and Ward’s family where Stewart would agree to pay a significant amount of money in exchange for Ward’s family relinquishing any legal claims it may have against him. The settlement would likely be confidential and not contain any admission of wrongdoing. Given that a civil trial involving Stewart would attract headlines and remind the public of Ward’s death, Stewart would seem to have good reason to seek a settlement and avert a trial.

Possible suspension and loss of endorsement deals for Stewart through 'morals clauses'

NASCAR has broad legal authority to discipline drivers, who are not represented by a union and do not enjoy collectively bargained protections. NASCAR’s system of justice is generally handled by its “Deterrence System,” which establishes appropriate penalties for various infractions and offers disciplined drivers the opportunity to appeal a sanction to its final appeals officer (Bryan Moss).

Whether NASCAR takes action against Stewart remains to be seen. While Stewart is a NASCAR driver, the incident did not occur at a NASCAR-sanctioned race. A sprint car race, moreover, is an entirely different form of racing from NASCAR or IndyCar. To the extent NASCAR disciplines Stewart, it would be based on his conduct outside the scope of his employment as a NASCAR driver. NASCAR punishing Stewart would be akin to the NFL or the NBA suspending one of its players for an off-field or off-court incident that embarrasses the league and causes it reputational damage (for example, the NFL suspending Ray Rice for domestic abuse or the NBA suspending Raymond Felton for gun charges).

Stewart also faces potential adverse consequences in the form of terminated endorsement deals. Stewart reportedly has lucrative endorsement deals with such blue chip companies as Coca-Cola, Chevrolet and Mobil 1. While I have not reviewed Stewart’s endorsement contracts, they likely contain “morals clauses.” These clauses allow the company to end or suspend an endorsement contract with an athlete whose misconduct brings shame onto the company. Typically, morals clauses are broadly written to include any misconduct -- whether it leads to criminal charges, civil lawsuits or simply bad press -- and that is especially true with major companies. Stewart, like Tiger Woods, could face a loss of endorsement deals because of the controversy, settling aside whether it leads to any legal consequences.

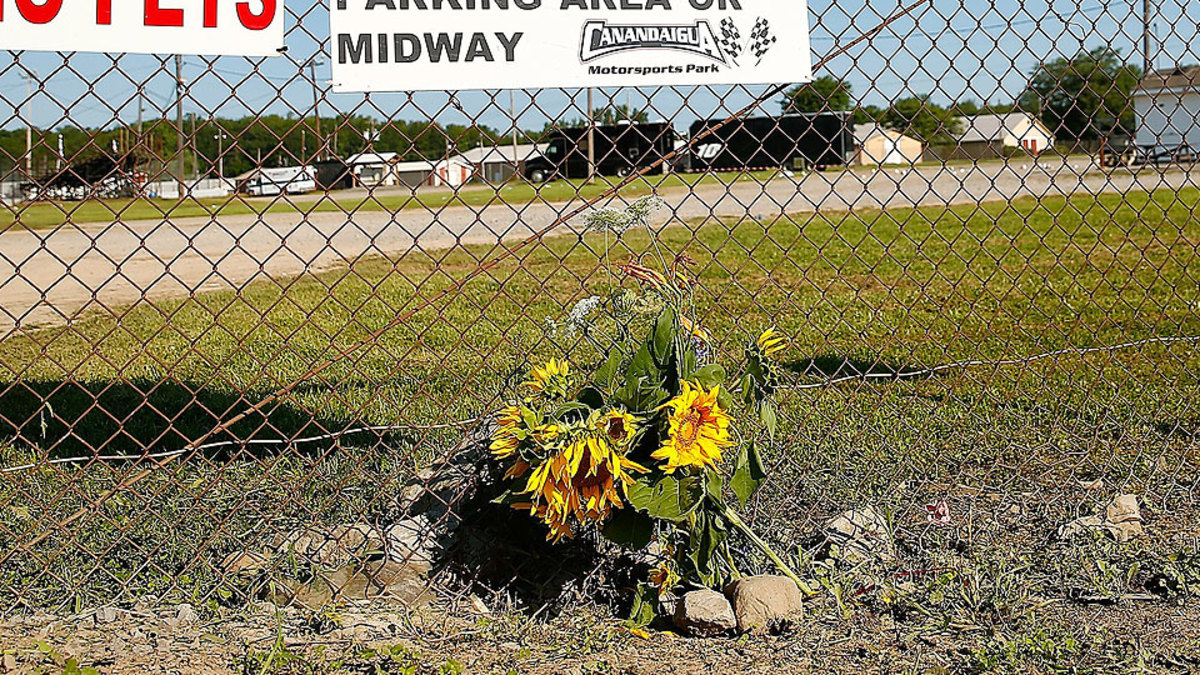

Possible — but unlikely — liability for Canandaigua Motorsports Park and race organizers

At this point, there is no reason to believe that Canandaigua Motorsports Park or the race’s organizers engaged in conduct that would lead to civil liability. Information would need to surface that the track’s dimensions or other features somehow contributed to Ward being struck by Stewart’s race car, and as of now there are no indications that the track played such a role. This is further supported by the fact that the track has been around since 1953 and does not appear to have a history of safety problems. Similarly, officials in charge with keeping the race safe appeared to have done their job by issuing a caution flag after Ward’s race car hit the outside wall. Officials had no realistic way of stopping Ward from leaving his car and confronting Stewart.

SI LONGFORM: Life and death and dirt track racing (by Lars Anderson)

Michael McCann is a Massachusetts attorney and the founding director of the Sports and Entertainment Law Institute at the University of New Hampshire School of Law. He is also the distinguished visiting Hall of Fame Professor of Law at Mississippi College School of Law.