What are the greatest sports teams ever?

Debating the GOAT—or Greatest of All Time—for a particular sport is probably one of the most common and hotly debated discussions. Ask a bar full of fans: What are the greatest sports teams ever? and you’ll likely receive differing responses and spark a heated argument. The discussion starts as a simple list. But as more possibilities emerge, the debate over the qualities and statistics that actually define a great sports team boils over. Is it the number of championships? Or is it record-breaking stats or win-loss records? Can you even compare a team in the NBA or MLB to Australian rugby or women’s soccer?

At the center of that conversation is where Sam Walker, founding editor of The Wall Street Journal’s sports section, found himself as he set out to write Captain Class, his new book about the 16 of the alltime best sports teams—and what exactly they have in common.

Walker’s fascination with the topic started when he was 11 years old, when his little-league baseball team suddenly went undefeated one summer, but he ultimately decided to dive into the debate after the Boston Red Sox won the World Series in October 2004.

Buy Now

Captain Class

by Sam Walker

Identifying greatest teams in history and identifies the counterintuitive leadership qualities of the unconventional men and women who drove them to succeed.

After spending the season studying the team as part of research for a book about competing in a fantasy baseball, Walker garnered that the club was fun, but generally undisciplined, and by July, when they fell 9 1/2 games behind the New York Yankees, he wasn’t surprised. But then something changed. Just like Walker’s little league team went from “nosepickers who let balls roll between their legs” to kids who could make competent plays, the Red Sox fought back, snuck into the postseason and then mounted that historic ALCS comeback on the Yankees, climbing back from an 0-3 deficit to win the series.

How did it happen? That’s what Walker dives into in Captain Class, as years of reporting and research led him to a common element at the core of great sports teams: one player—often an unacknowledged one—with a specific but surprising set of characteristics and leadership traits.

Walker ultimately chose the greatest sports teams ever—from the 1955-60 Montreal Canadiens, to the 1986-90 New Zealand All Blacks, to the 1996-99 U.S. Women’s National Team. Below, we asked Walker and SI editors and writers to tackle the debate for the NFL, NBA, MLB and club soccer.

NFL

Sam Walker: The NFL was a tough nut to crack, especially after this year's Super Bowl. Let me be clear: The 2001–17 New England Patriots are probably the best football team of all time. Given that they played in an era when the salary cap was wreaking havoc on teams, their record is all the more impressive. But here's the thing: If you take a sober look at their numbers, it's hard to say that it's appreciably more impressive than what the 1981–95 San Francisco 49ers achieved. Both teams won Five Super Bowls over a long stretch of dominance and posted elite winning percentages and Elo Ratings. In the final analysis, I don't believe that you can claim to be one of the greatest teams in sports history unless you achieved something unique. Because they're so similar, the Pats and 49ers can't make that claim. They cancel each other out. The Green Bay Packers of the 1960s were an easier cut. Another one of my rules is that a team must have had every possible opportunity to assert its dominance. The Packers won three of their titles before the NFL champion took on the winners of the AFL. So off they went. I think the mark of a great NFL team is a simple one: It won the most championships in short order. And by that logic, Jack Lambert’s 1974–80 Pittsburgh Steelers, winners of four in six seasons, are the only inarguably "special" NFL team. One caveat: Talk to me next February. If the Patriots win another Super Bowl, they will supplant the 49ers and join the list.

Chris Burke: The greatest dynastic run in NFL history is still unfolding. We are watching it happen in real time. Since 2001, the New England Patriots have failed to win the AFC East just twice. They have finished with fewer than 10 wins in one season, 2002, when they checked in at 9-7 and lost the division to the Jets as part of a three-way tiebreaker. The Patriots cannot match the Steelers’ accomplishment of four Super Bowl wins in six seasons (1974-79), but Bill Belichick’s club did win three in four between 2001-04 and now has taken home two of the past three.

What really sets the Patriots’ success apart, though, is longevity. The Steelers’ dynasty was confined mainly to those aforementioned six years—that franchise did not make the playoffs at all from 1948-71 and missed again in both ‘80 and ‘81. Only the 49ers, with their stretch from 1981 to about ‘97, can challenge the Patriots’ dominance over the long haul. New England has more Super Bowl wins (five) and more division titles (14) during its dynasty years than San Francisco captured.

There’s also no reason, as of yet, to believe the Patriots are about to fade. They will enter the 2017 season as the defending Super Bowl champions, having pulled off one of the sport’s all-time great comebacks—a rally from 28-3 down to knock off Atlanta in overtime, lest anyone need a reminder. Now 39-year-old QB Tom Brady, arguably the best ever at his position, has said he wants to play several more seasons. Belichick, now 65, is still running circles around most other front offices around the league. The Patriots will be heavy favorites to win the AFC East again—they have captured eight straight division titles and finished first in 13 of the past 14 seasons.

All of this has come with everything from the salary cap to free agency to how the NFL’s schedule is designed to promote parity league-wide. The Patriots only non-playoff year since 2003 came in ‘08, when Brady fell to a knee injury in Week 1. They still ripped off 11 victories with Matt Cassel at the helm, only to be nipped for a postseason spot. The team’s overall record the past 16 seasons: 196-60, including the perfect 2007 regular season.

This has been an unbelievable run of success for the Patriots. And it’s still not over.

NBA

SW: This entire debate comes down to how you rate the Bulls. While they might have been the most dominant team at their peak, I didn't include them for one simple reason: their achievements weren't unique. The Celtics won 11 titles in 13 seasons, which trumps Chicago's six in eight. And the Bulls couldn't match the incredible consistency and longevity of the Spurs, who were an excellent, championship-level team for 19 years (and counting). Some analysts argue that the Bulls, who played at a time when there were 27 to 29 teams in the NBA, faced longer odds of winning a title and would have been as dominant as the Celtics if they, too, had played in an era when there were only eight to 14 teams. But I'd argue, as many do, that during the early days of the NBA, the talent was more concentrated and teams stayed together longer, which made the average team tougher to beat. If you look at the modern NBA, there are really only eight to 12 "good" teams and (if we're being honest) five legitimate contenders. As for the 1999-2002 Lakers: One of my principles was that to all but eliminate the possibility that a team's dynasty was as much a function of luck as it was of a genuine winning culture, I decided to limit my evaluation to teams that were dominant for at least four seasons. Those Lakers were only great for three.

Ben Golliver: I would take both the 1990s Bulls and the Popovich/Robinson/Duncan/Leonard Spurs over the early Celtics, who should always be regarded as the sport’s original dynasty but not be granted automatic supremacy over modern champions. While the Walker cites the “concentration of talent” argument on behalf of Boston, suggesting Bill Russell and company had to defeat tougher opposition because there were fewer teams at that time, the talent that was being concentrated wasn’t very impressive. The athleticism, physicality and technique of players improved significantly from that early era into the 1980s and beyond, as did scouting, efficiency-based strategy on both offense and defense, and training techniques.

Basketball is a sport with a long history of being dominated by singular stars, and it was easier for that type of player to rack up accomplishments in the early days. The gap between greats like Russell and Wilt Chamberlain and their peers is significantly larger than the gap between Michael Jordan and his peers or LeBron James and his peers. The modern global talent pool is significantly deeper—way more people are playing basketball—and there are functional systems in place around the world to identity and cultivate that talent from an early age.

Watch YouTube film from that era and it’s impossible to imagine the Celtics remaining competitive against quality teams from the modern era. This is simple evolution. If the definition of “Greatest Team” amounts to counting rings, then give it to Boston. But if we’re searching for the group that could withstand the test of time and remain competitive across eras, the only teams that should be considered are those from the 1980s on.

One big reason: modern rule changes, especially the three-point line. Basketball now is a much different sport. No single big man could dominate like Russell in the modern game because the three-point shot has proven to be a great equalizer. Let’s not overlook the league’s financial success, either: it’s harder to build and keep a core group together when organizations have to jump through salary cap hurdles and face constant competition from their fellow billionaires who are, by and large, willing to spend big in pursuit of a championship. As legend has it, the Celtics were able to draft Russell, in part, by wooing the owner of the Rochester Royals with a free week of Ice Capades shows. Something tells me that wouldn’t have been enough to convince Cleveland to pass on James in 2003.

At this moment, Jordan’s Bulls would still be my pick. Their perfect 6-0 run through the Finals could easily have been 8-0 had he decided not to step away from the NBA to play baseball. While Chicago did play in the expansion era, Jordan dominated a long list of Hall of Famers with long and legendary careers, and he never needed a Game 7 in the Finals. The 1996 Bulls also won more games and posted a better point differential than any of the Spurs teams or Celtics teams.

That said, the Spurs are a very compelling choice and they don’t get nearly enough attention in this discussion. This might be a cop out, but I’ll parse this by giving the Bulls the “Greatest Team” title and the Spurs the “Greatest Organization” title. I don’t see any way San Antonio’s cumulative winning percentage over two decades is matched by another franchise in my lifetime. Nevertheless, I’d have a hard time betting against Jordan’s Bulls in a hypothetical Finals match-up with Tim Duncan’s Spurs.

MLB

SW: This just in: Baseball analysts love numbers... According to the most advanced metrics, a list of the best teams in baseball history would look quite different than mine. The Atlanta Braves had two of the most quantitatively superior single-season teams of all time, for instance—by wins above replacement—while the 1927 Yankees were the best statistical team of all time. But in baseball, all that really matters is winning the World Series—lots of times in short order. And by that standard, the Braves (with only one title over that span of dominance) don't rate. And while the '27 Yankees won again in '28, they didn't make the World Series the following season. The best evidence of all, I think, is that the only team to win five consecutive titles, the 1949-53 Yankees, weren't statistically remarkable at all.

Ted Keith: There is no disputing the unparalleled success of the 1949 to ‘53 Yankees, who are the only team to win five consecutive World Series titles, nor of their absurd dominance in that era that saw them win 15 pennants and 10 championships from 1947 to ’64. We can marvel at what they achieved but we can only wonder at what might have happened had they been forced to contend with the land mines of the modern era: a three-round gauntlet of postseason competition; a fully integrated sport that pulls elite talent from all over the world; and a free agent system that allows that talent to be distributed more readily across the sport.

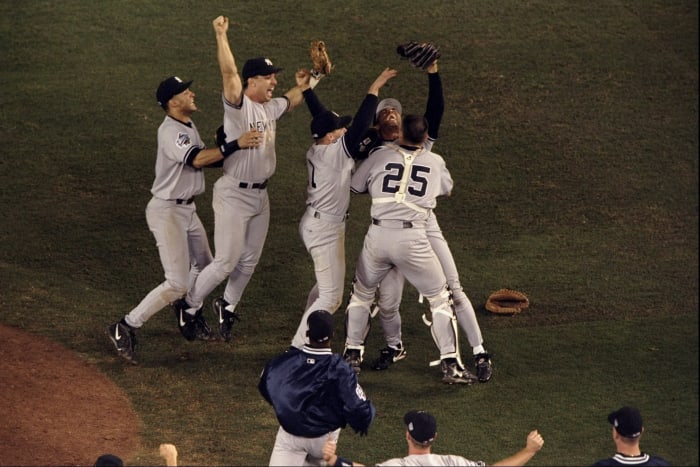

Indeed, since the dawn of free agency in 1975 only one team has won three straight titles: the Yankees of 1998, ’99 and 2000. New York also won a title in 1996 and was three outs away from a fifth title in six years in 2001. And no, these were not the recklessly spending Yankees of the early 2000s that bought superstars in an effort to buy championships. No, this was a team constructed smartly and patiently a decade earlier, one centered around homegrown stars like shortstop Derek Jeter, catcher Jorge Posada, starting pitcher Andy Pettitte, reliever Mariano Rivera and center fielder Bernie Williams, and supplemented with strong players of varying pedigrees like outfielder Paul O’Neill, first baseman Tino Martinez, third baseman Scott Brosius and pitcher David Cone.

Though loaded with talent, Jeter and Rivera were the only two Hall of Famers in their primes on those teams. New York wasn’t even the best regular season team in baseball from 1996 to 2001—the Atlanta Braves won seven more games—but the Yankees were the best when it mattered most. They went an incredible 14-2 in postseason series, a mark better than even their predecessors of half a century before. They were 56-22 in the postseason overall, .718 winning percentage that, if applied to a 162-game season, would have matched the best record in the history of baseball. And in the Fall Classic, New York was even more unstoppable, dropping just one World Series game during their three-peat and at one point winning 16 of 17 Series games, again surpassing the best of the 1949 to ’53 group, whose best three-year Series stretch saw them go 12-3 from 1949 to ’51.

Those post-war Yankees may have been the most successful in baseball history. But it was the late-90s edition that set a standard that will likely never be reached again.

Club soccer

SW: Nothing turned my hair grayer than trying to analyze club soccer. Because every nation has its own domestic professional league with its own slate of annual titles, the sport is maddeningly fragmented. While teams from top leagues in England, Germany, Spain, and Italy attract most of the attention, clubs from smaller countries like Portugal, Scotland, and Uruguay sometimes put up similar numbers. Worst of all is the fact that club teams from different nations don’t meet with any regularity beyond multinational competitions like the Champions League and Copa Libertadores. The majority of the roughly three-dozen dynastic club soccer teams throughout history were eliminated for the same two reasons: They either lacked sufficient opportunity to prove themselves (many played before the big continental tournaments were founded) or their achievements didn’t stand out. But there were still a bunch of clubs that met both standards in some way. All of them balanced home-league domination with success on the international stage, and many could boast of being the best professional team a country had ever produced.

To whittle the list down, I took a closer look at the overall quality of the domestic leagues these teams played in and whether they “ran the table” during their dynasties without suffering some significant and unforgivable losses. I also factored in the results of a handful of matches in which two of these teams actually met on the field. In the end, it came down to Barcelona (2008-12) and Ajax (1969-73). To be honest, it was a toss up. Ajax lost its domestic league once, but to Feyenoord, a European Cup winner. And Ajax won more European titles than that Barcelona team. In the end, I gave the nod to Barca for three reasons: It won so many different trophies, it had been an excellent team for a while before its peak, and it posted the highest club-team ELO rating of all time.

Brian Straus: The only people who should blame graying hair on any exercise related to Barcelona are opposing coaches. Not only is Walker correct in his conclusion that the 2008-13 Blaugrana were the best club team of all time, he’s more right than he realizes.

It’s instinctive when reviewing someone else’s ranking to want to criticize or debate their conclusions. But the only issue we have here is with the premise that comparing clubs is tougher than comparing countries. National teams are unstable by nature. They play infrequently and so rely on larger pools of players instead of defined rosters. They’re all-star teams trying to win short tournaments. The Brazil of the late 1950s and early ‘60s—his top national team—claimed consecutive World Cups. But they fell short in the four South American championships staged from 1957 through ‘63. That says something about the player pool, or Brazil's priorities, or both. Either reflects on the national team.

Clubs aim for something more observable and quantifiable. The best ones build rosters and cores, identify tactics and styles and then week-to-week and season-to-season, hope that identity leads to trophies. Walker has some data that backs up his conclusion, led by FCB’s 15 major honors (including two FIFA Club World Cups and two UEFA Champions League titles). That’s the quantifiable part. But it’s the observable part unique to club soccer that makes this the sort of open-and-shut case that can’t really be built around a national team.

That Barcelona team, managed by Pep Guardiola and then the late Tito Vilanova in 2012-13, redefined the planet’s most popular sport in an era when we thought we’d seen everything. During a time when speed and fitness are easier to cultivate than technique and when the demand for results frequently leads to defensive, conservative tactics, Barcelona produced attacking soccer of unsurpassed beauty and efficiency. Its intelligent pressing and passing resulted in wins, routs, statistical dominance, highlight-reel goals and a renewed appreciation for skill over size and brains over brawn. It was a revolution—or soccer’s apotheosis—led not by foreign signings in their prime but by players developed at FCB's own youth academy. The domestic core of Xavi Hernández, Andrés Iniesta, Sergio Busquets, Gerard Piqué and Carles Puyol also formed the spine of the Spanish squad some would claim was superior to Pelé’s Brazil. Add Lionel Messi to that mix—he joined Barcelona at 13—and complementary, big-splash acquisitions like Thierry Henry or David Villa, and it’s almost unfair.

Ajax did some of that, too. Total Football was also revolutionary. But much of that sprang from the genius of Johan Cruyff and Rinus Michels, both of whom went on to help lay the foundation at Barcelona. And Ajax didn’t play opponents with billion-dollar, multi-national rosters or face the schedule congestion, travel, scrutiny or post-Bosman free agency that Barcelona overcame. Guardiola’s FCB will be a team we’ll still celebrate when we have gray hair, but it shouldn’t be the cause.